Cincinnati is one of those cities pollsters love to cite as representative of America as a whole. It sits at the bottom end of Ohio, perhaps the most mid-American of all states. While nominally a northern town, it is separated from Kentucky only by the Ohio River, and shares not only its southern weather, but many of its attitudes.

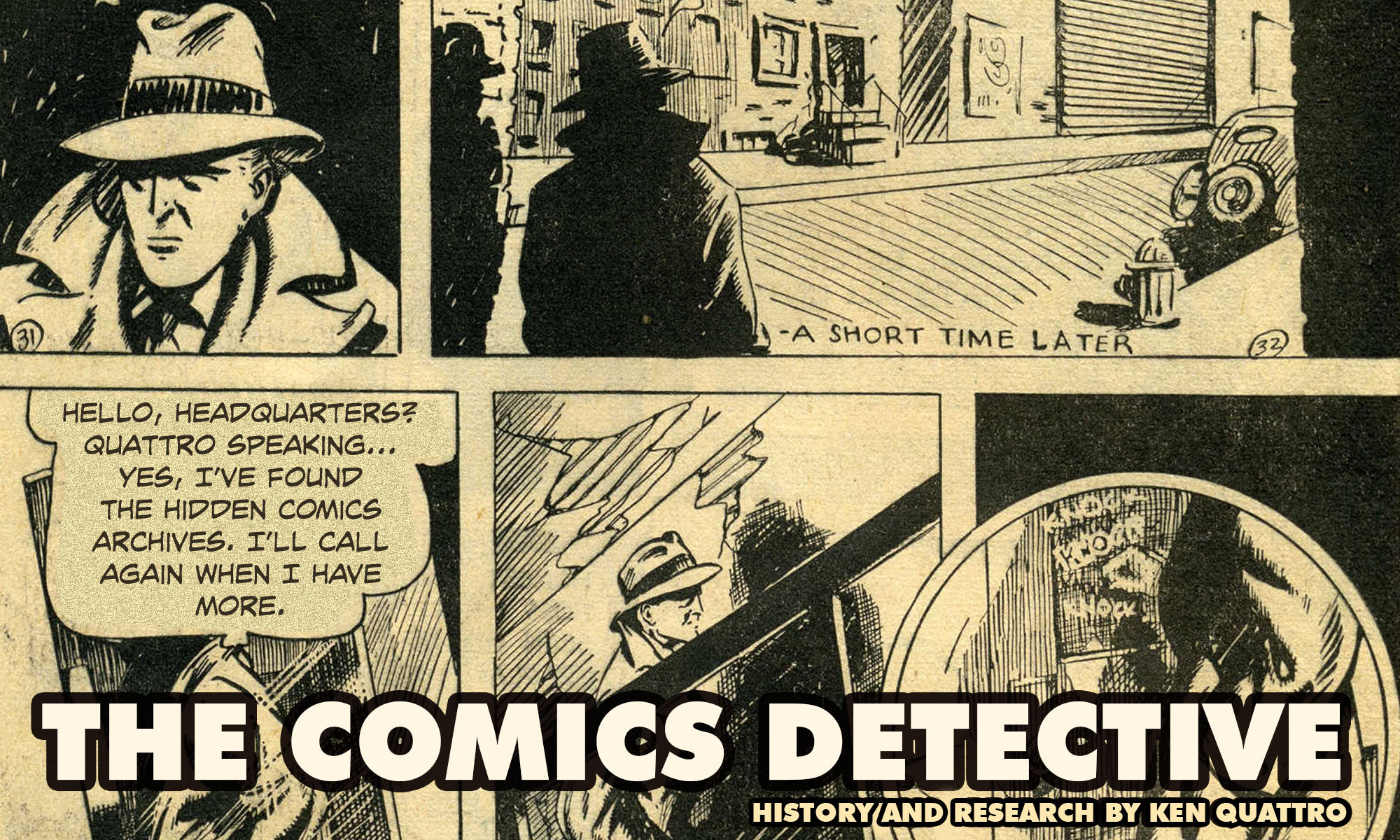

Directly across the Ohio lies Covington; so close it may as well be part of the Queen City. They two cities share an airport and the largest newspaper in the region, the CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, covers it as closely as it does its hometown. That is why the minister of Covington’s First Methodist Church was treated like one of its own.

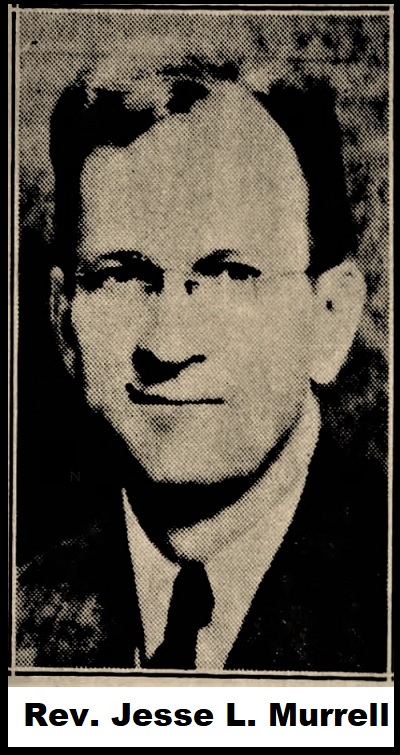

Rev. Jesse L. Murrell (1938)

“Dr. Jesse L. Murrell, new pastor of First Methodist Church, Covington, and Mrs. Murrell were guests of a reception given Thursday night at the church, Fifth and Greenup Streets. Dr. Murrell was transferred to Covington recently from Daytona Beach, Fla.” [“In Social Circles,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, July 12, 1941.]

Jesse Lobbin Murrell was a Kentucky native, born in the tiny town of Craycraft in sparsely-populated Adair County in 1889. The son of a farmer, Murrell trained for the clergy and received his first pastoral assignments in small towns in Illinois. After serving as a minister in the Navy during the Great War, Murrell got married in 1920, and moved to Florida, where he became an associate pastor of the large White Temple Methodist Episcopal Church in Miami.

Murrell served several other congregations in Florida before he became pastor of First Methodist in Daytona Beach leading to his position back in his home state of Kentucky.

Murrell brought with him extensive experience working with young people, from various roles with the YMCA, organizing Boy Scout troops and teaching. It was not surprising, then, that he chose a subject related to children as the focus of a sermon he gave in honor of National Family Week on May 2, 1948.

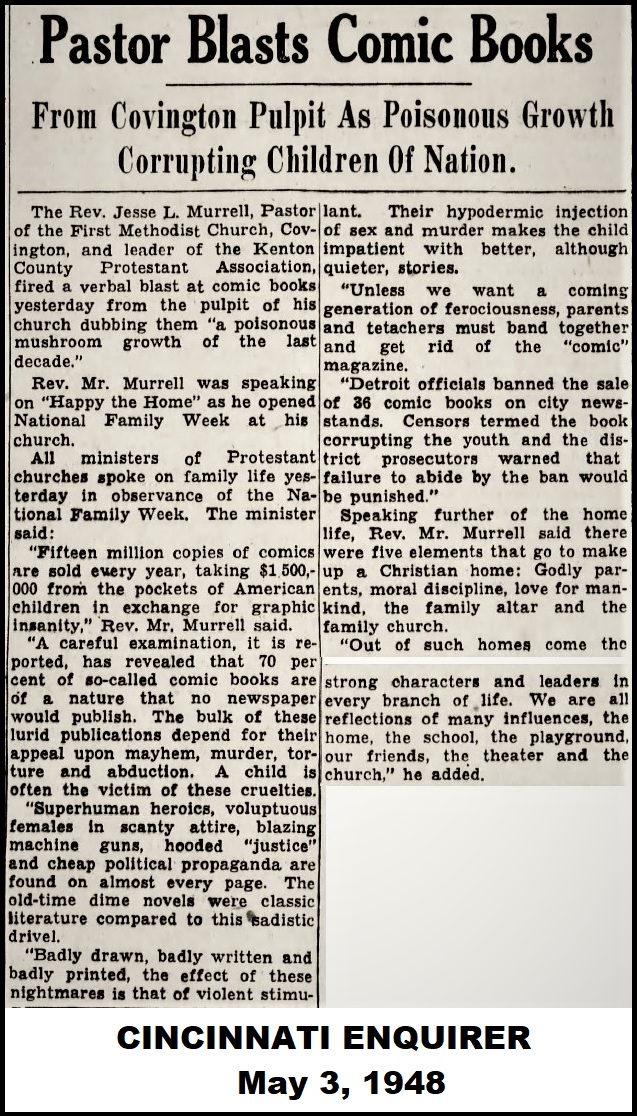

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER (May 3, 1948)

“Fifteen million copies of comics are sold every year, taking $1,500,000 from the pockets of American children in exchange for graphic insanity.”

“The bulk of these lurid publications depend for their appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction. A child is often the victim of these cruelties.”

“Superhuman heroics, voluptuous females in scanty attire, blazing machine guns, hooded ‘justice’ and cheap political propaganda are found on almost every page.”

“Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed, the effect of these nightmares is that of violent stimulant. Their hypodermic injection of sex and murder makes the child impatient with better, although quieter, stories.”

“Unless we want a coming generation of ferociousness, parents and teachers must band together and get rid of the ‘comic’ magazine.” [Pastor Blasts Comic Books,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 3, 1948.]

Rev. Murrell’s sermon was not given in a vacuum. Comic books had become controversial in the early months of 1948, due in large part to the efforts of Dr. Fredric Wertham, whose very public criticism of comics had appeared in various national magazines and on radio programs.

Murrell was apparently well-versed on the subject. Much of his sermon seemed to be drawn from previous critic’s diatribes against the medium. His use of the term ‘hooded justice’ was a direct quote from author Sterling North’s infamous column from 1940 entitled “A National Disgrace.” His other complaints echoed those made by Gabriel Lynn in his two pamphlets written for the Catholic sponsored Catechetical Guild—THE CASE AGAINST THE COMICS and THE TEACHER AND THE COMICS–both booklets Murrell was known to have read. The March 2nd broadcast of the radio program “Townhall Meeting of the Air” featured a debate on the subject and had made it a part of the national conversation. And of course, Wertham’s attacks appeared in numerous publications and provided plenty of fodder.

“A reporter sensing something here that might be of interest to the public sent a report of the sermon to the Cincinnati papers who carried the comic magazine portion of the sermon in prominent display the next day. The broadcasting stations picked up the idea and flung it abroad with the result that fan mail began to flood the minister. Phone calls commanded him and urged a follow-up.” [“What One Sermon Did,” uncredited press release, c.1948.]

The reactions to Murrell’s sermon were quick and probably stunning to the middle-aged clergyman who was more likely used to his sermons being ignored rather than seeing them run on the front page of a newspaper. He did not hesitate, though, in turning his words into action.

The local newspaper ran an editorial a few days after Murrell’s sermon crediting him for providing “food for thought” and agreeing that “there is a point beyond which bad taste or poor literature should not be encouraged or tolerated.”

“That sort of stuff almost inevitably leads to crime or the warping of character if it becomes a steady ‘literary’ diet.” [“Dangerous ‘Comics,’ CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 6, 1948.]

Murrell’s words had impact beyond the editorial page. Within weeks, the Covington City Commission took up the matter “as to how the output of such literature [comic books] might be curbed.”

“Members of the commission sought the advice of Stanley Chrisman, City Solicitor, as to what steps were possible under the law to limit the sale of objectionable printed material. Chrisman replied that more study was necessary before he could give a final opinion, but that he would say, offhand, that the Kentucky statutes offered no effective curb.” [“More ‘Battle Plans’ Offered In Fight On ‘Comic Books;’ Law Said To Be Ineffective,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 22. 1948.]

Murrell, already recognized as the leader in the battle against comics, was asked his opinion.

“I am leaning heavily upon the power of moral suasion,” he replied, “to accomplish the aim of discouraging injurious publications.”

“I am in favor of freedom in this and other matters to as great a degree as possible, and I feel that an aroused public opinion and the spread of information concerning the books must be looked to for more accomplishments in curbing the sale of such literature.” [“Battle Plans,” ibid.]

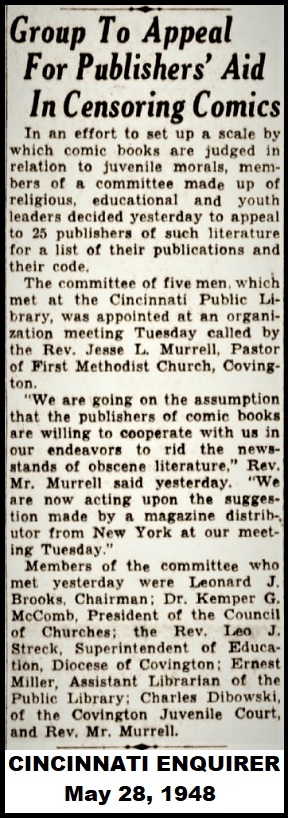

On May 25, Murrell held a meeting at Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills Public Library and invited representatives of various youth organizations, religious groups, and several city employees. The meeting had a very specific purpose.

“The clergyman [Murrell] was urged by personal appeals and fan mail to organize a movement to improve the type of juvenile comics now on sale.”

“‘Among the undesirable types of comics are to be included those which stress crime, sex, horror, sadism, racial or class prejudice.’” [“Intercity Groups Formed To Press Cleanup Of Comics; Committee To Make Report,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 26, 1948.]

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER (MaY 28, 1948)

The meeting was considered important enough that local magazine distributors were joined by an emissary of a large New York City concern, who made the case that they had little choice in what they put on newsstands.

“Representatives of local news and magazine sale companies which provide comics for dealers told the group they were powerless to change the comic books they send to the newsstands, since they are obliged to accept shipments as they come from publishers.”

“J. Louis Motz of the Motz News Co. admitted that there are both good and bad comics handled by his agency. Robert Dunham, representing the Independent News Co., New York, said his firm, which publishes 42 comic magazines, makes an effort to keep them inoffensive, but that in the last 18 months sales of less desirable comics has increased.” [“Intercity Groups,” ibid.]

Unmentioned was the fact that Independent News was part of National Periodical Publications, and under the same ownership as DC Comics. While they were not the main target of comic critics, they had a vested interest in staying on the good side of consumers and always presented to the public the face of a concerned corporation.

“A committee was appointed to find out what has been done in other cities to improve the quality of comics available to young people, and to adopt standards for judging whether or not certain reading material is objectionable from a moral standpoint.” [“Intercity Groups,” ibid.]

Essentially, this meeting formed what would become known as the Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books. In this first iteration, the group consisted of five men, which included several other clergymen, a librarian, and a member of the Covington Juvenile Court.

“We are going on the assumption that the publishers of comic books are willing to cooperate with us in our endeavors to rid the newsstands of obscene literature,” Murrell was quoted, “We are now acting upon the suggestion made by a magazine distributor from New York [Dunham] at our meeting Tuesday.” [“Group To Appeal For Publishers’ Aid In Censoring Comics,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 28, 1948.]

Apparently, Dunham had suggested the group approach the publishers individually to get the changes they desired. It was a cleverly calculated suggestion, as he knew that National Comics (DC) was in a much better position than some of its competitors to address the Committee’s concerns.

It was soon after their first meeting that the Committee began sending out letters to the various comic book publishers in New York City, making their plea for improvement of their publications. The responses came back, assuring the purity of their publications and cooperation with the Committee.

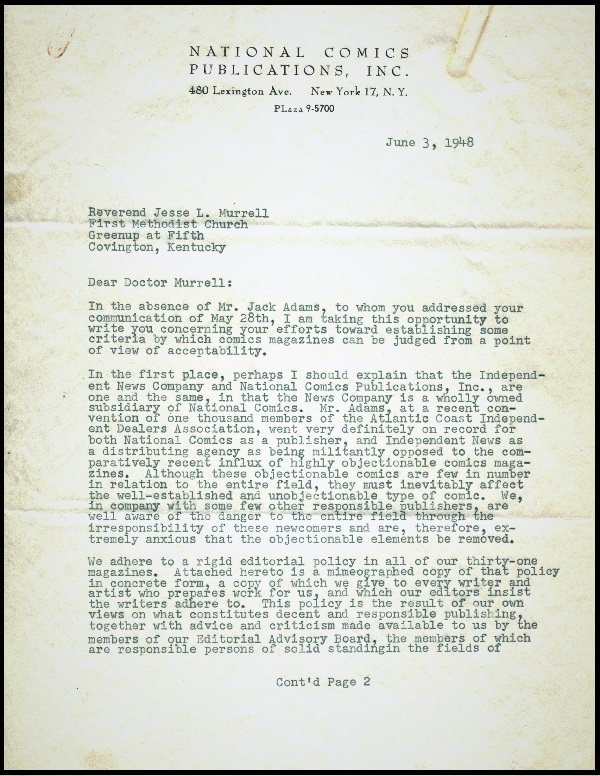

Letter from Whitney Ellsworth to Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, pg. 1 (June 3, 1948)

pg. 2

“We, in company with some few other responsible publishers, are well aware of the danger to the entire field through the irresponsibility of these newcomers and are, therefore, extremely anxious that the objectionable elements be removed.”

“We adhere to a rigid editorial policy in all of our thirty-one magazines. Attached hereto is a mimeographed copy of that policy in concrete form, a copy of which we give to every writer and artist who prepares work for us, and which our editors insist the writers adhere to.”

“We do not claim to be perfect—but we do claim that we strive to keep our standards up; if we occasionally are guilty of a minor lapse, we usually recognize the lapse ourselves,and redouble our efforts to see that such lapses are reduced to the irreducible minimum.”

“We assure you of our fullest cooperation, and any suggestions you may have toward improving any of our magazines will meet with the friendliest scrutiny.” [Letter from Whitney Ellsworth to Reverend Jesse L. Murrell, June 3, 1948.]

Another publisher, Educational Comics, Inc. (EC), was still dealing with the tragic death of its founder Max C. Gaines in a boating accident the previous August. His young son William had taken over the reins and had not yet had time to put his own stamp upon the company. That would come soon.

In the meantime, the EC comic book line was made up of holdovers from the elder Gaines tenure, a mixed bag of innocuous kid’s comics, a Western, a superhero title and a couple of crime comic books. Their response letter touted the company’s membership in a seminal publishers’ association meant to ward off critics of the industry.

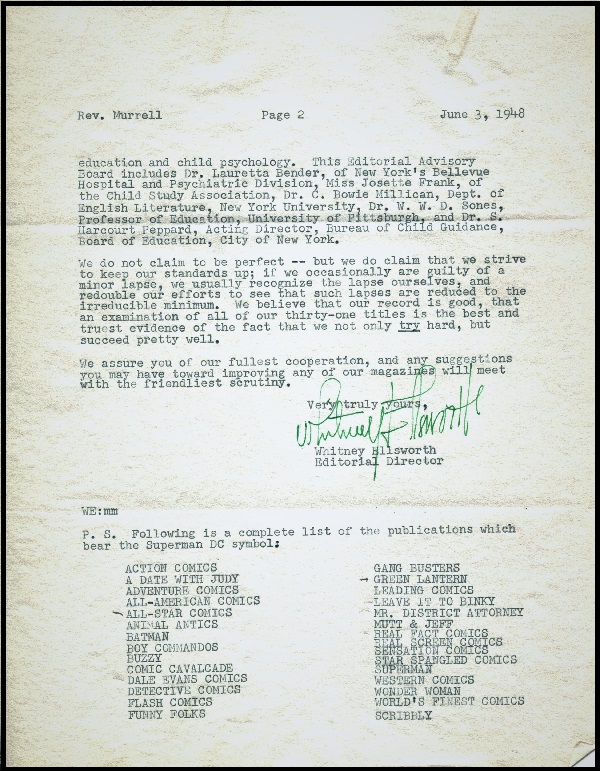

Letter from Sol Cohen to Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, pg. 1 (June 24, 1948)

pg. 2

“We are a member of the Association of Comic Magazine Publishers (ACMP). This association has adopted a code of minimum editorial standard. They are now conducting an intensive drive to secure the membership of all the comic magazine publishers in the United States and their pledge to abide by the comics code. The Code, in addition to being publicized in the press, will be sent to local societies, civic groups, and distributors of magazines.”

“The association also announces that it is considering a commissioner whose function it will be to survey the entire industry in the light of the comics code, and suggest changes, if necessary, as well as to impose restrictions on those members of the Association whose magazines do no adhere to the particulars of the comics code.” [Letter from Sol Cohen to Reverend Jesse L. Murrell, June 24, 1948.]

Cohen included the text of the entire ACMP Comics Code and his assurance that of “our desire to cooperate with you and your groups to the fullest extent.” [Cohen, ibid.]

“At the outset, a policy of cooperation with the publishers and distributors in improving the quality of comic magazines was adopted; but since this had little effect, the Committee decided that its strategy with the public would be that of education rather than censure as some advocated.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “The Greater Cincinnati Committee On Evaluation Of Comic Books,” July 1964.]

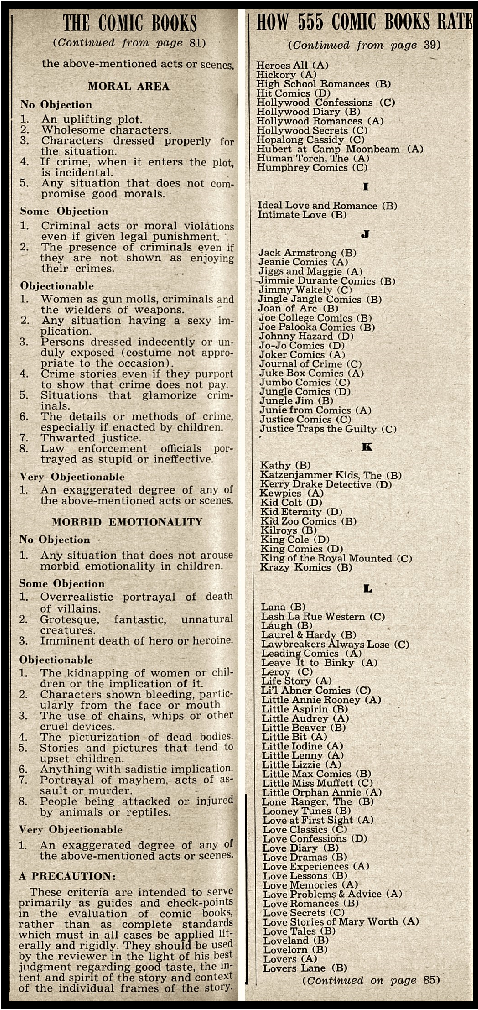

To perform their accepted task, the Committee would have to have their own guidelines by which to evaluate comic books. By October 1948, Murrell and the Committee had worked out the first draft of a comics code that they would use as a set of standards to rate the comic books they considered.

“The three standards set up are cultural, moral and morbid emotionality. Poor art work, printing injurious to children’s eyes, obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, divorce treated humorously or represented as glamorous, sympathy with crime and the criminal, prejudice against race, color, religion or nationality are included under the cultural area.”

“Situations having a sex implication, women as gun molls, criminals and wielders of lethal weapons, persons dressed indecently, crime stories glamorizing criminals, law enforcement officials portrayed as stupid or ineffective are included as objectionable features of comic books in the moral area.”

“Portrayal of kidnapping of women or children; gory scenes such as bleeding, showing of bodies, pictures having a sadistic implication, acts of mayhem, assault or murder and pictures tending to upset the nervous composure of children will be regarded as objectionable by the committee.” [“Comic Books—Graded By Code,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Oct. 1, 1948.]

At the same time, he was putting together the comics evaluation committee, Murrell’s primary concern were his pastoral duties and the reconstruction of the First Methodist church. It had nearly been destroyed in a January 1947, fire and its grand reopening came along in late summer of 1948. It is not clear if Murrell’s sudden notoriety increased his congregation size, but a few more parishioners contributing to the collection plate would have been a welcome result.

Armed with their code restrictions, the Committee set about training 35 volunteers to be comic book reviewers. Once again meeting at the Walnut Hills Library, the Committee was convened by Murrell and the reviewers were coached by Dr. Herbert B. Weaver, a psychology professor from the University of Cincinnati.

“The charts to be used in evaluating comics found on local newsstands were worked out by Dr. Weaver and a committee.”

“Each person present took three comic books to judge and will return the report next Tuesday night in the same place. Each book then will be judged by a second person. When a book is rated objectionable by a unanimous vote of the reviewers, the publishers will be asked to suspend its publication. By such a method Dr. Murrell and the committee hope to enlist the cooperation of the publishers in improving the type of comic book sold.” [“Volunteers Are Briefed In Comic-Book Reviewing,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Oct. 20, 1948.]

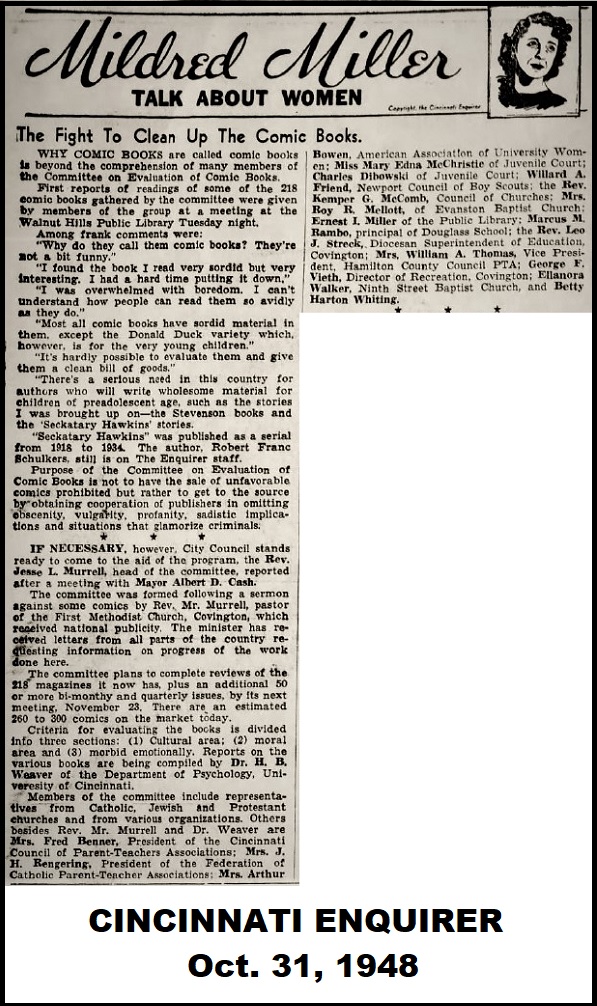

The efforts of the Committee were covered by the press with the enthusiasm generally reserved for the hometown baseball team. Not only news stories, but local columnists found ways to work mentions of the evaluation group into their writings.

“Why comic books are called comic books is beyond the comprehension of many members of the Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books,” wrote Mildred Miller in her column aimed at women.

“First reports of readings of some of the 218 comic books gathered by the committee were given by members of the group at a meeting at the Walnut Hills Public Library Tuesday night.”

“Purpose of the Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books is not to have the sale of unfavorable comics prohibited but rather to get to the source by obtaining cooperation of publishers in omitting obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, sadistic implications and situations that glamorized criminals.” [Miller, Mildred, “Talk About Women,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Oct. 31, 1948.]

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER (Oct. 31, 1948)

Indeed, the Committee’s approach of working with publishers instead of resorting to ordinances banning comics, stood in stark contrast to many other cities and organizations which exhibited no tolerance for comics at all. Still, Murrell was willing to accept any help he could get.

“If necessary, however, City Council stands ready to come to the aid of the program, the Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, head of the committee, reported after a meeting with Mayor Albert D. Cash.”

“The committee plans to complete reviews of the 218 magazines it now has, plus an additional 50 or more bi-monthly and quarterly issues, by its next meeting, November 23.” [Miller, ibid.]

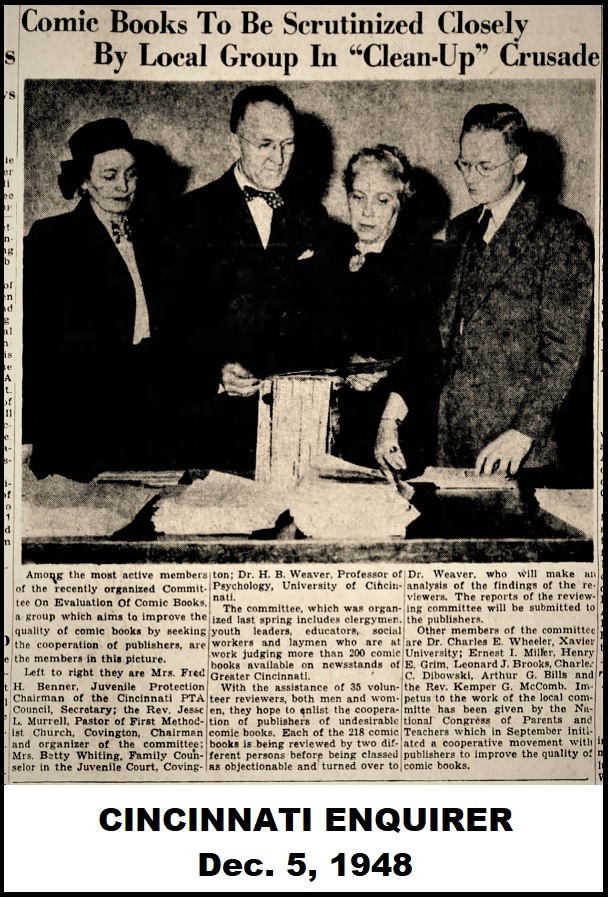

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER (Dec. 5, 1948)

The Committee had gained national attention and it was reported that the National Congress of Parents and Teachers (forerunner of the PTA) was supportive and cooperating with the Committee’s goals of publisher engagement.

Following the lead of the national organization, the Ohio Congress of Parents and Teachers met in Akron in December 1948, to coordinate efforts throughout the state in addressing the “curbing objectionable comics, movies and radio programs.”

“At the first hearing in Akron recently, it was made clear that although not all comics are objectionable, some illustrate the most advance techniques of delinquency. Local civic, community and educational authorities joined with the committee in this opinion. Among those in the audience were representatives of a prominent comic book publishing company who showed a willingness to cooperate with public sentiment.” [“Ohio PTA Congress Moves To Unify Review Of Comics,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Jan. 16, 1949.]

The appearance of this unnamed representative from a New York comic publisher was an indication at how seriously the industry was taking the Committee. It would behoove them to work with such a group instead of the chilling alternative of having their publications banned by local ordinances.

Other cities took notice of Cincinnati’s approach and modeled it. Up the road in Dayton, a similar comics study committee was formed involving the local PTA, religious and civic groups and Joseph G. Schaller Jr., an editor with Dayton-based George A. Pflaum Co., publishers of the Catholic comic, TREASURE CHEST.

Joseph G. Schaller and members of Dayton comics committee (Jan. 20, 1949)

Despite the Committee’s insistence upon appealing to comic publishers as the preferred tactic to combat offending comics, the City Council Law Committee of Cincinnati held their own meeting to consider an ordinance “which would ban the sale and distribution to minors of comic books and material depicting crime.”

“The Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, Chairman of the Cincinnati Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books, which is trying to suppress distribution of objectionable comic material, believes that ‘you have to get the publishers or there will be bootlegging going on.’” [“Boycott Of Dealers Urged,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Feb. 1, 1949.]

The politicians listened to Murrell’s suggestions and made a few of their own. The head of the Law Committee suggested that Murrell solicit the cooperation of the Druggists Association and “undertake an effective campaign that will bring the ‘heat of public opinion’ to bear against distributors and dealers.”

“Mayor Albert D. Cash suggested the possibility of a ‘boycott,’ to be conducted under an accepted committee, that could say to a druggist or some other outlet for comic books on the objectionable list: ‘You either refrain from selling these books or we won’t deal with you.’” [“Boycott,” ibid.]

Murrell asked the Law Committee for time to use his method of persuasion to effect voluntary change. In response, the Law Committee gave him one month before they would pass a city ordinance.

It took Murrell and the Committee only a week to get back to the City Council. On February 7, 1949, the Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books announced the completion of their first list of acceptable and objectionable comics.

“Rev. Mr. Murrell told the City Council Law Committee that his group hoped to have ready in about a week a list of acceptable comic books for distribution by the PTA’s.”

“The Law Committee currently is trying to determine what recommendations to make to Council on the distribution of comic books. It has before it an ordinance that would ban sale of objectionable comics to children.”

Mayor Cash proposed the creation of a city-run committee to meet with retailers and newsstand owners “to see what could be worked out on a cooperative basis.”

“Ultimately, he said, it might be necessary to license comic book dealers.” [“Nearly Half Of Comics O.K.’d,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Feb. 8, 1949.]

There was some grumbling about the licensing proposal, as it would appear to be an additional tax on retailers, so the idea was tabled for further consideration.

Local magazine distributor Louis Motz was anxious to put the onus on the comic book publishers to control their content.

“[Motz] said the best way to tackle the problem was at the source—the publishers. If the Rev. Mr. Murrell cannot get their cooperation, then ‘I’ll back him 100 percent.’” [“Nearly Half,” ibid.]

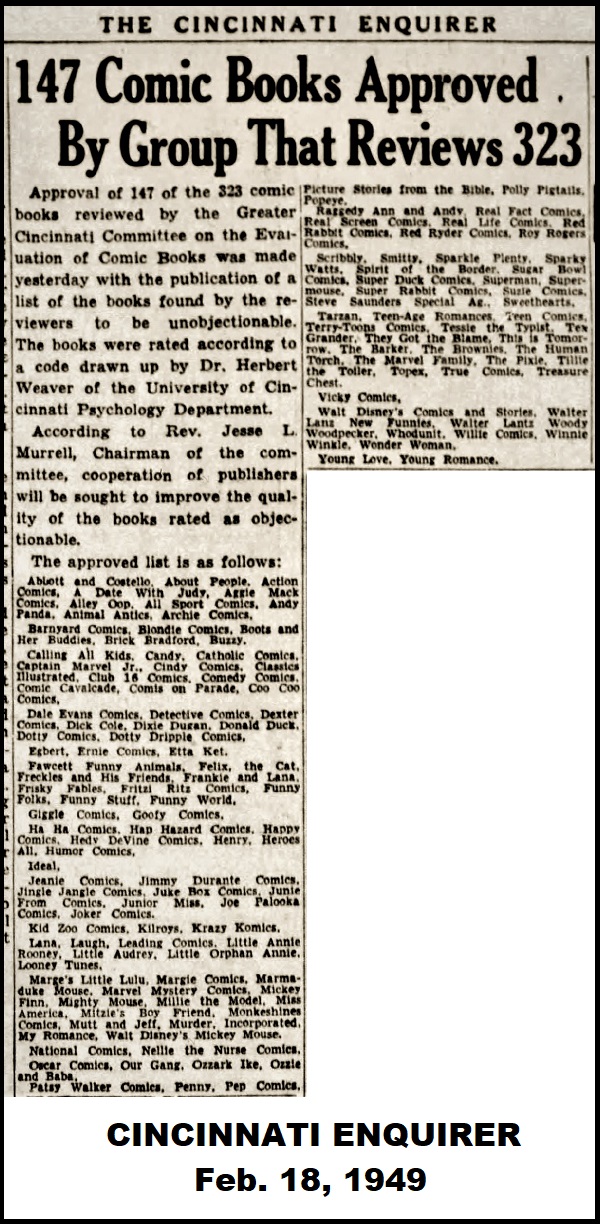

First list of comic books evaluated (Feb. 18, 1949)

The complete list of acceptable comics appeared in the Feb. 18th edition of the CINCINNATI ENQUIRER. Using their own criteria, the Committee approved 147 comic titles out of the 323 that they reviewed. Parenthetically, the similarly-tasked Dayton committee released their own list of approved comics in May, with 159 comics getting their approval. The Cincinnati committee also printed 10,000 copies of its list for distribution throughout the country.

The list contained some curiosities. While SUPERMAN and ACTION COMICS were approved by the Committee, ADVENTURE COMICS, starring the younger version of the Man of Steel, “Superboy,” did not. BATMAN was excluded, but his companion title, DETECTIVE COMICS, was approved. “Wonder Woman” met the same fate. Her self-named title was fine by the Committee’s standards, but something about her other starring vehicle, SENSATION COMICS, kept it off the list. At least they had partial validation. Their “Justice Society of America” cohorts “The Flash” and “Green Lantern” were nowhere to be found and neither was ALL STAR COMICS, which featured all the JSA.

Similar irregularities were scattered among other comic publishers as well, indicating that it was basically the luck of the draw as to which comic reviewer rated which comic. Some obviously had stricter personal guidelines than others.

Apparently, individual comic publishers were sent copies of the Committee’s list along with a request from Murrell for their reactions. As before, Whitney Ellsworth, Editorial Director for National Comics (DC) responded personally and in detail.

“You ask for opinions and suggestions concerning your method of evaluation. As I see it, there are only a couple of approaches that I could wish to see clarified. It seems to me that the profile chart might be of more value to the editor and publisher in locating the exact spot in a story in which an ‘objectionable’ situation appears if the chart could be made specific in this respect. I must confess that it is in many cases difficult specifically to locate objections falling within the moral area.”

“This examination of the moral area leads directly to my second suggestion—namely, that some way be found, if possible, to rephrase and/or make more specific point No. 4 under the subhead ‘objectionable’ in the moral area. I agree, of course, that the practice indulged in by a very few publishers of glorifying crime and the criminal for 68 panels and then saying in panel 69 that crime does not pay is a vicious and cynical approach.” [Letter from Whitney Ellsworth to Dr. Jesse L. Murrell, March 1, 1949.]

Ellsworth’s focus on the moral aspects of the objectionable comics was a canny decision. He was writing to a Methodist minister, after all, and morality was an important consideration in the judging of the comics. Furthermore, his sly interjection of the term “crime does not pay” was probably an indirect indictment of competing publisher Lev Gleason’s very popular crime comic book of the same name.

Despite their mutual agreement about the cynical glamorizing of crime in some comics, Ellsworth offered the contrary opinion “that valuable moral lessons can be taught when stories concerning criminals are presented from the standpoint of the Law, and showing criminals to be the low-grade creatures they are…” [Ellsworth, ibid.]

The real concern Ellsworth came when he noted the absence of certain DC titles from the “Approved” list. He spent the rest of the letter assuring Murrell of his company’s dedication to maintaining “a high standard of acceptability,” which was demonstrated by their use of an in-house editorial code and employing the services of an Editorial Advisory Board. To assist Murrell and the Committee in the next comic book evaluation, Ellsworth sent along a package containing a sample issue of each comic they published.

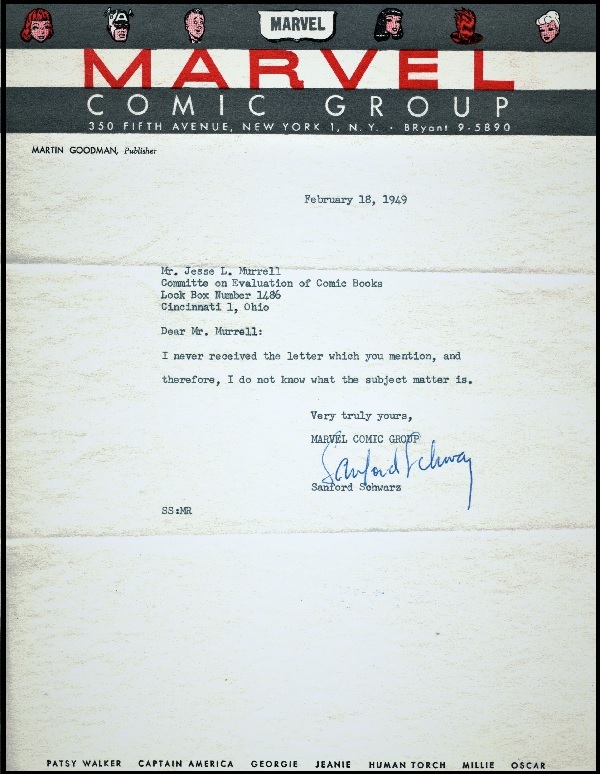

Not all publishers were as forthcoming. Curiously, one other large publisher’s response, dated the same day the list was published, was short and seemingly oblivious.

Letter from Sanford Schwarz to Jesse L. Murrell (Feb. 18, 1948)

“I never received the letter which you mention, and therefore, I do not know what the subject matter is.” [Letter from Sanford Schwarz to Jesse L. Murrell, February 18, 1949.]

The release of the Committee’s list came at a time when the comics controversy had become a part of the national conversation. Religious, educational, and civic groups all seemingly had their own ongoing comics studies. Censorship and bans were debated at city and statewide levels.

Notably, although the ACMP had been formed in July 1948, and members of the group tacitly supported the efforts of the Cincinnati committee, it took until January 17, 1949, until it created its own office to “screen” the comics of its membership. Yet, comics bearing the ACMP stamp of approval began appearing on newsstands in February 1949, long before any of them could have possibly been screened.

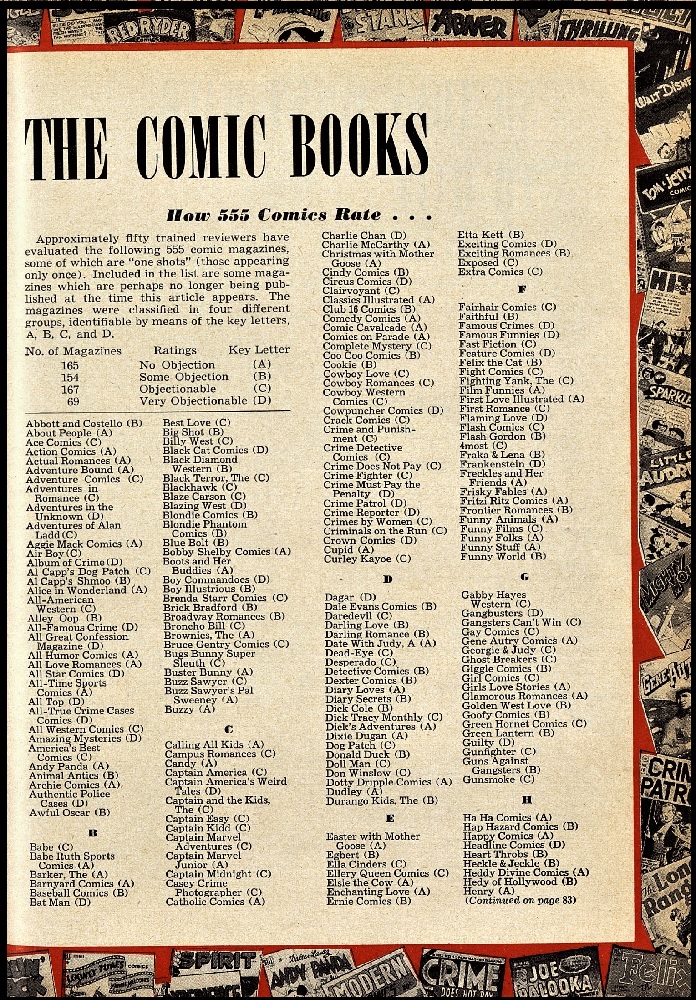

Meanwhile, self-proclaimed, and media-created experts were everywhere giving their opinions on and Rev. Murrell joined them. He appeared at PTA meetings, before church congregations, gave talks to politicians and law enforcement personnel. His lectures recounted the efforts of the Committee and he penned articles with titles such as “What Can Be Done About Comic Books” based upon his insights.

“What Can Be Done About Comic Books?” pg. 1 (c. 1949)

pg. 2

pg. 3

pg. 4

pg. 5

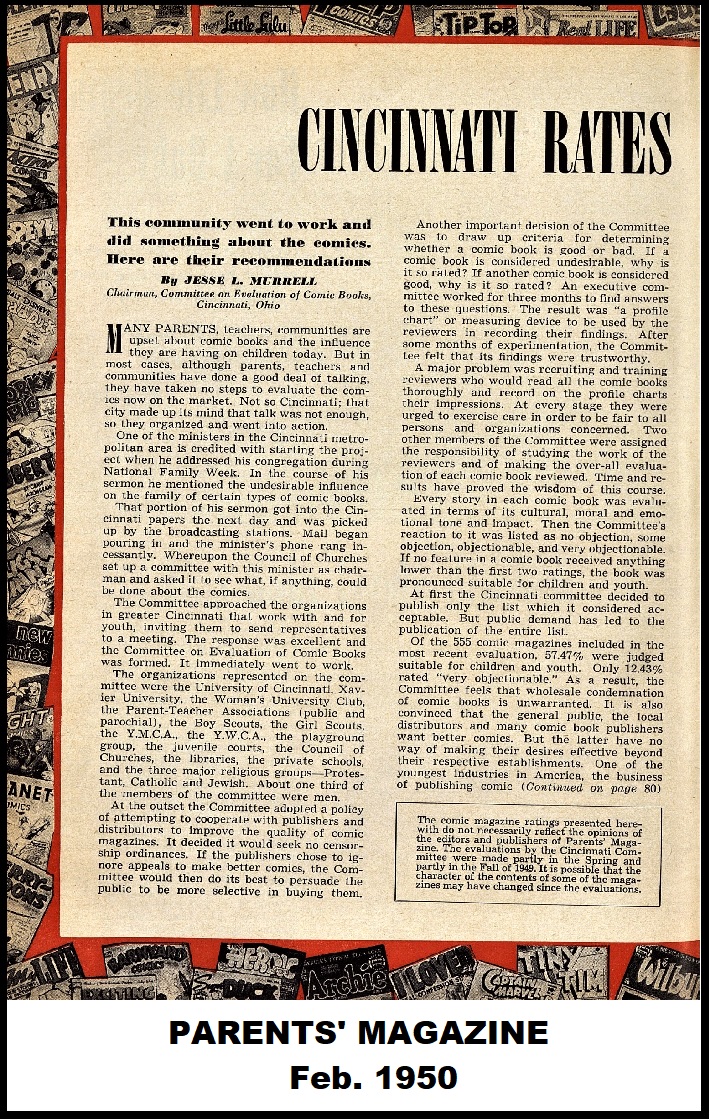

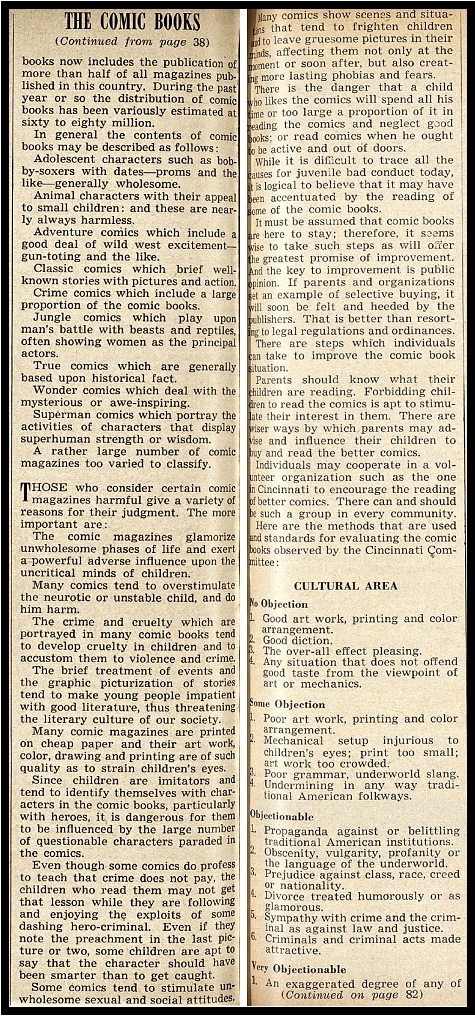

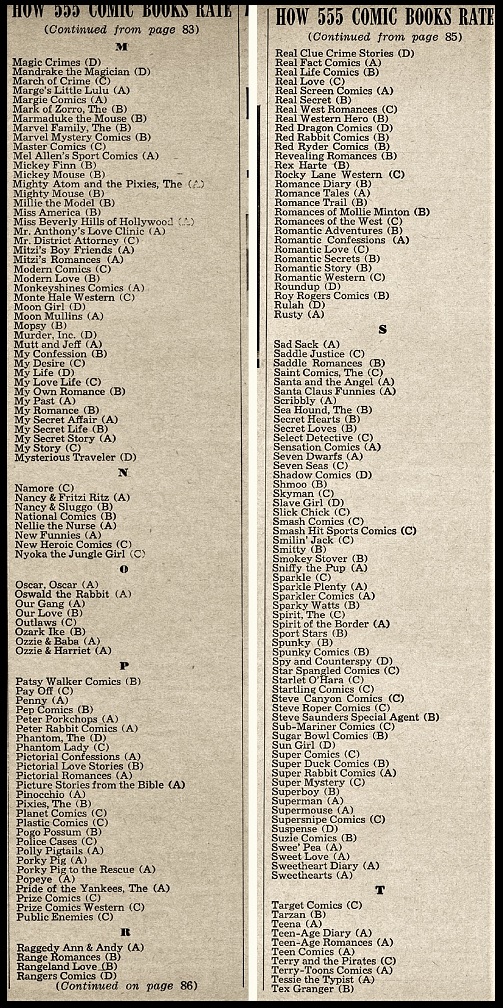

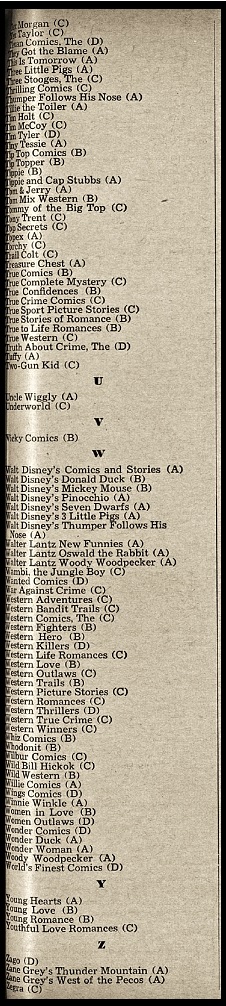

All the while, the Committee was busy evaluating a new crop of comic books. They announced that the comics surveyed would be classified into four groups: “No objection,” “Some objection,” Objectionable,” and “Very objectionable.” The group of reviewers grew to 60 and the number of titles reviewed ballooned to 531.

“‘The last comic books we reviewed averaged considerably higher than those in previous reviews,’ the Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, Chairman of the committee, said yesterday. ‘The features we deplored most in the earlier comics have almost completely disappeared and several of the books which we place on the ‘very objectionable’ list have ceased publication.’”

“‘I am very much encouraged over the evident improvement in this form of literature. While it may be hard to assess causes, it is only fair to claim for our committee a reasonable proportion of the credit.’” [“New List Of Ratings Put Out,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Dec. 18, 1949.]

Murrell was wise to downplay the effect the first list issued by the Committee had upon the comic book industry. While it added to the pile of criticism and scrutiny coming at the publishers, alone it probably had little meaning to them. Furthermore, actual sales and the changing tastes of comic book readership likely affected what appeared on newsstands more than the words of any concerned parents or critics.

By the end of 1949, the super-hero comic had almost disappeared. Except for a few franchise-defining stars, most publishers had given up on the genre. For the time being. Romance, Western, humor and crime comics dominated, with science fiction and especially horror comics just making their footholds. If Murrell thought his committee had thwarted the threat posed by comics with his 1948 list, he had no idea of what was lurking just over the horizon.

The Cincinnati Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books was to get a big boost in notoriety when its 1949 list appeared in the Feb. 1950 issue of PARENTS’ magazine, along with an article written by Murrell titled, “Cincinnati Rates The Comic Books.”

PARENTS’ MAGAZINE, pg. 1 (Feb. 1950)

pg. 2

Writing in the third person, Murrell presented a brief history of the Committee’s formation and detailed its composition and how it performed its reviews. Some of the numbers used in this article varied from the first reports of the list back in December 1949, but the conclusions were the same.

pg. 3

pg. 4

pg. 5

pg. 6

“Of the 555 comic magazines included in the most recent evaluation, 57.47% were judged suitable for children and youth. Only 12.43% rated ‘very objectionable.” As a result, the Committee feels that wholesale condemnation of comic books is unwarranted. It is also convinced that the general public, the local distributors and many comic book publishers want better comics.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Cincinnati Rates the Comic Books,” PARENTS’, Feb. 1950.]

The fact that PARENTS’ would choose to publish the Cincinnati committee’s list and Murrell’s accompanying article reflected its analogous position on comic books.

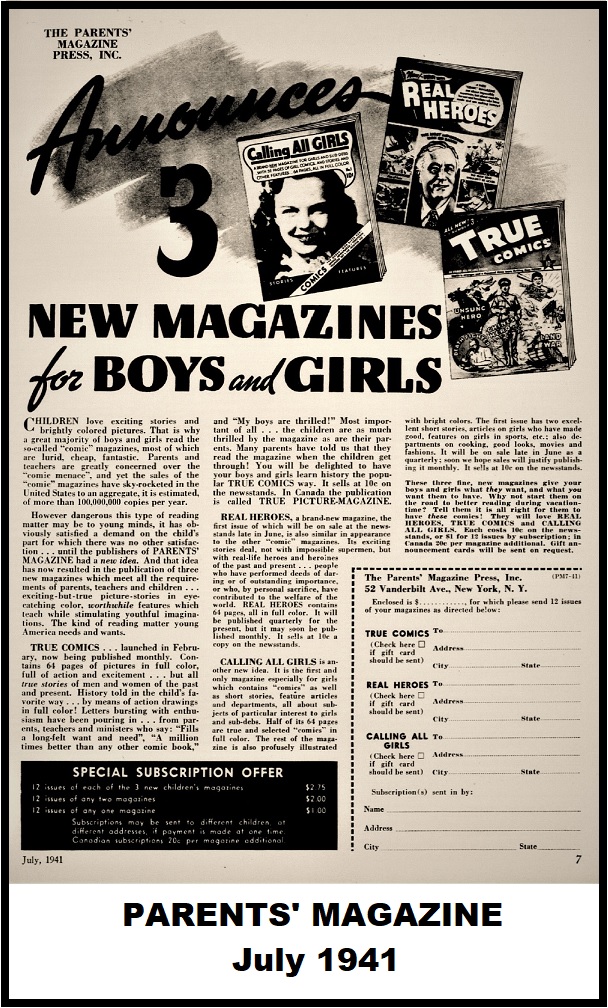

The magazine’s publisher and president of the Parents’ Institute, Inc. was George J. Hecht. Hecht. His long career had been devoted to the betterment of child rearing and he had a very public love-hate relationship with comic books.

At the beginning of his career during WWI, Hecht formed the Bureau of Cartoons, which encouraged American cartoonists to produce propagandist work in support of the war effort. And even after founding PARENTS’ magazine, he published an article supportive of comic strips, such as Florence Yoder Wilson’s “Should Kids Read Comics?” in its November 1928 issue. But his views on comic books was mixed.

“Presenting facts and figures on the extent of the reading of comic magazines by the nation’s youth, George J. Hecht, president and publisher of Parents Magazine, yesterday attacked this form of children’s reading, terming it a threat to character development, and called on the publishers of books for children to counteract the comics’ effects.” [‘Comics Effects On Youth Scored,” NEW YORK TIMES, Nov. 6, 1941.]

Written years before Murrell had formed his Cincinnati comics evaluation committee, Hecht’s comments were amazingly similar. What made his words even more striking was the fact that he was a comic book publisher himself.

“He said his magazine, in an effort to ‘fight fire with fire,’ was now publishing three comic magazines, hoping thereby to check the comics ‘by substitution rather than prohibition.’ The publisher declared, however, that he would be glad ‘all comics, including our own, were put out of business.’” [“Comics Effects,” ibid.]

Beginning with TRUE COMICS in the spring of 1941, and soon followed by CALLING ALL GIRLS and REAL HEROES that fall, were shining examples of what he and others would call “good comics.” Needless to say, the output of Parents’ Magazine Press (the publisher of Hecht’s comic book line) routinely made the list of approved comics.

PARENTS’ MAGAZINE ad for new comic book line (July 1941)

The PARENTS’ magazine appearance greatly enhanced the profile of Murrell and the Cincinnati committee. Columnists, commentators, and news outlets cited its results often and Murrell was quoted frequently. Even governmental institutions, right on up to the US Congress, took the Committee’s work seriously and cited its ratings whenever comics were the matter at hand.

The Committee’s ratings proved so popular that for a time, they were published twice a year, in spring and fall, in issues of PARENTS’. Each time, Murrell would write an accompanying article giving context to the results. In the Oct. 1950 PARENTS’ he happily noted that “the ratings published in the February, 1950, issue of PARENTS’ MAGAZINE showed that 57.47 percent of these magazines were suitable for children and young people, 69.18 percent have made that rating in this latest round of reviews.”

‘In assessing reasons for the present higher level of comic books, the Cincinnati group credits, first, the national outcry against certain types of comics during recent years; second, selective buying made easier by such evaluation lists as this one; third, the discovery by publishers that the better comic books sell more extensively as a rule.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Cincinnati Again Rates The Comics,” PARENTS’, Oct. 1950.]

Murrell was cognizant that other comic book critics, particularly Dr. Wertham, were making their cases and unlike Murrell and his Committee, these others were not as forgiving of the industry. Bans and boycotts sprung up, publicity stunts in the form of comic book burnings held for the benefit of news cameras, were plastered on the front pages of newspapers and politicians looking to make political hay, took it up as a cause. The measured approach of the Cincinnati committee and PARENTS’ magazine must have seemed a welcome alternative to beleaguered comic publishers.

It must be noted, though, that the comic book industry did not make it easy on themselves. Despite Murrell’s assertion that the publishers had realized that “better comics” (that is, approved comics) sold more, the success of the newly re-imagined EC (now Entertaining Comics) comics line, featuring the horror, science fiction and crime genres, had spawned a number of imitators. In pursuit of a quick buck, some publishers pushed the limits of “good taste” with depictions of gore and violence that generated sales but made even comic book defenders uneasy.

Murrell’s previous happiness with the improved state of comic book content must have taken a hit, as he noted the increase in the troubling genres and mentioned it in his 1951 PARENTS’ article.

“There has been a considerable increase in mystery and horror in comic books and this accounts in part for the fact that 9 percent of the comic book evaluated here fall in the category of ‘very objectionable’ whereas there were only 6 percent a year ago.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “How Good Are The Comic Books?” PARENTS’, Nov. 1951.]

By the following year, Murrell commented upon the Committee’s perception of further degradation in comic book content.

“The proportion of comic books that deal with crime remains the same over the last four years but today there is a sharp increase in war comics, nearly all of which are poor according to the Committee’s standards. There are comics that deal with witches and ghosts, and most of these are frightening. Some portray grotesque and sinister creatures. Others deal with mystery and horror in a way that was considered disturbing. There are comics that carry the reader into outer space where he finds strange, fearful weapons and creatures. Most of these were judged unsuited to children.”

“Nearly all of the 11 magazines dealing with the American Indian and many of the 45 Western comics put the Indian in a bad light. This was considered undesirable and unfair to the many American Indians who are law-abiding citizens. The criteria of the Cincinnati Committee condemn all acts, words and deeds that tend to belittle or misrepresent any such group.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Annual Rating Of Comic Magazines,” PARENTS’, Nov. 1952.]

It is a revealing that the Committee’s complaints regarding the comics they evaluated extended to the depiction of a minority group such as Native Americans. The progressive attitudes of many comic book critics of this era have often been overlooked and as consequence, they have been stereotyped as narrow-minded reactionaries.

Murrell’s 1953 article tried to remain upbeat, but he regretfully remarked that the Committee reviewers were, “distressed, however, to find that there has been a downward trend during the past two years and attributes this to the great influx of comic magazines that treat war, ghosts, witches, outer space filled with grotesque and frightening creatures and presenting weird and frightful scenes and situations.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Annual Rating Of Comic Magazines,” PARENTS’, Oct. 1953.]

More and more the complaints of the Cincinnati reviewers paralleled the criticisms of Wertham, et. al. The ACMP stamp of approval on a comic was basically meaningless as it had no enforcement capability behind it for violators and so it was generally ignored by the publishers. Unrestricted and facing fierce competition, many comic book publishers sought the surest path to sell their comics and if that was through depiction of graphic violence and gore, so be it.

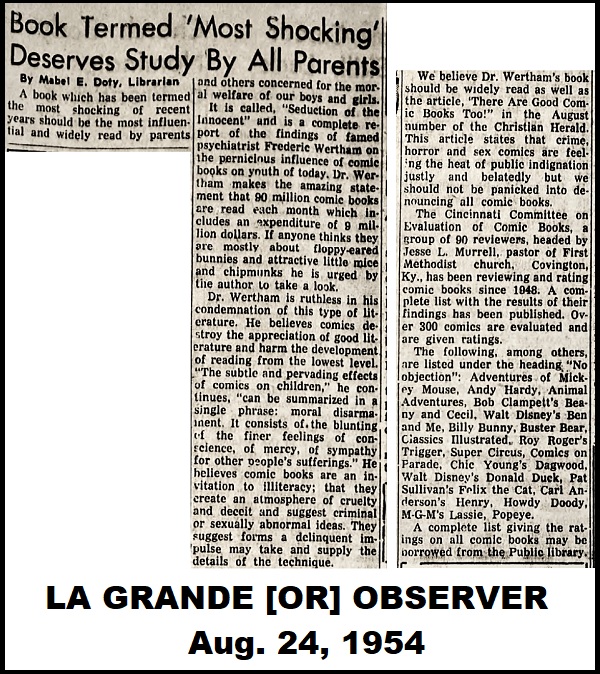

The article Murrell wrote to accompany the 1954 list was surprisingly short and noticeably, it did not mention the recent Senate hearings into the effects of comic books upon juvenile delinquency, nor Dr. Wertham’s notorious, best-selling book, SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT. This take-down of the comic book industry got most of the headlines and generated most of the discussion regarding comics, but Murrell seemed blissfully unaware.

“There are 384 comic books in the present listing and the Committee finds 59 percent of them suitable for children and young teenagers. That compares favorably with the 54 percent rated as suitable last year for boys and girls of these ages.”

“Each year the Committee’s influence has increased and it is doubtful if there is a county in the United States that has not received and used its materials.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Annual Rating Of Comic Magazines,” PARENTS’, Aug. 1954.]

LA GRANDE OBSERVER (Aug. 24, 1954)

Despite the stated goal of the Committee that their list be used to persuade comic book publishers to produce “better” comics, the fact was that the list was also being used a cudgel against the industry. It was cited in the Senate hearings and critics seeking to ban comics entirely used the list as a justification.

Still, it probably had some impact upon the comic publishers themselves. The impotent ACMP faded into history and a newly-formed industry group, the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) was created in its wake. Unlike its weak-willed predecessor, the CMAA determined that it had to have an independent censorship arm in which to enforce its proclaimed standards and to provide legitimacy to the Comics Code Approval stamp their comics would henceforth bear on their covers.

The CMAA’s formation had Murrell taking a victory lap, although with some qualifications.

“The leading crusader against objectionable comic books in Greater Cincinnati took a ‘wait and see’ attitude yesterday at the news that the comic book publishers had established a self-policing program.”

“‘They [comic publishers] have violated the moral code so flagrantly and so long that only action will show they mean what they say.’”

“If they really are sincere, it is a welcome and wonderful development. We hope that they have realized finally that they must reform or something worse than a clean-up will happen to them.’” [“Wait And See Is Policy Taken,” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, Sept. 17, 1954.]

Murrell’s tone was more pointedly critical than his PARENTS’ articles let on. Perhaps he was expressing his frustration with the publishers whom he had long tried reasoning with and who only decided to reform when facing bad publicity and threatened with governmental intrusion into their industry.

“‘If the really are sincere, it is a welcome and wonderful development. We hope that they have realized finally that they must reform or something worse than a clean-up will happen to them.’” [“Wait And See,” ibid.]

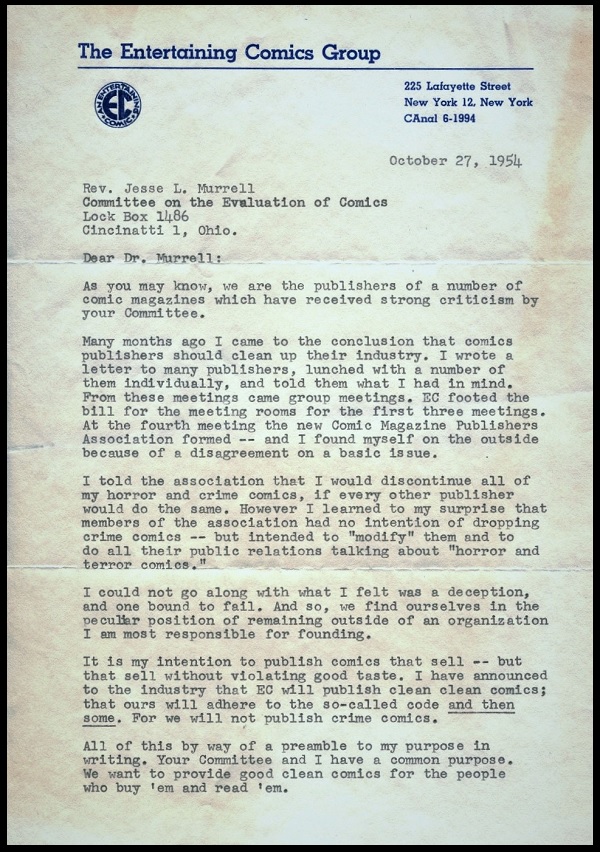

Not long after the formation of the CMAA and very soon after the announcement of Judge Charles F. Murphy to be its Code Administrator on October 1st, Murrell received a letter from William M. Gaines, publisher of EC comics. Its opening line was intriguing and in no way prepared Murrell for what the rest of the letter contained.

“As you may know, we are the publishers of a number of comic magazines which have received strong criticism by your Committee.”

“Many months ago I came to the conclusion that comics publishers should clean up their industry. I wrote a letter to many publishers, lunched with a number of them individually, and told them what I had in mind. From these meetings came group meetings. EC footed the bill for the meeting rooms for the first three meetings. At the fourth meeting the new Comic Magazine Publishers Association [sic] formed—and I found myself on the outside because of a disagreement on a basic issue.”

“I told the association that I would discontinue all of my horror and crime comics, if every other publisher would do the same. However, I learned to my surprise that members of the association had no intention of dropping crime comics—but intended to ‘modify’ them to do all their public relations talking about ‘horror and terror comics.’”

“I could not go along with what I felt was a deception, and one bound to fail. And so, we find ourselves in the peculiar position of remaining outside of an organization I am most responsible for founding.”

“It is my intention to publish comics that sell—but that sell without violating good taste. I have announced to the industry the EC will publish clean clean comics; that ours will adhere to the so-called code and then some. For we will not publish crime comics.” [William M. Gaines letter to Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, Oct. 27, 1954.]

At this point, Murrell must have wondered what this all had to do with him. Even though he may have welcomed Gaines’ newfound commitment to producing “clean clean comics,” he was probably suspicious of the publisher’s intent. That intent became clearer with the next paragraph.

Letter from William M. Gaines to Rev. Jesse L. Murrell, pg. 1 (Oct. 27, 1954)

pg. 2

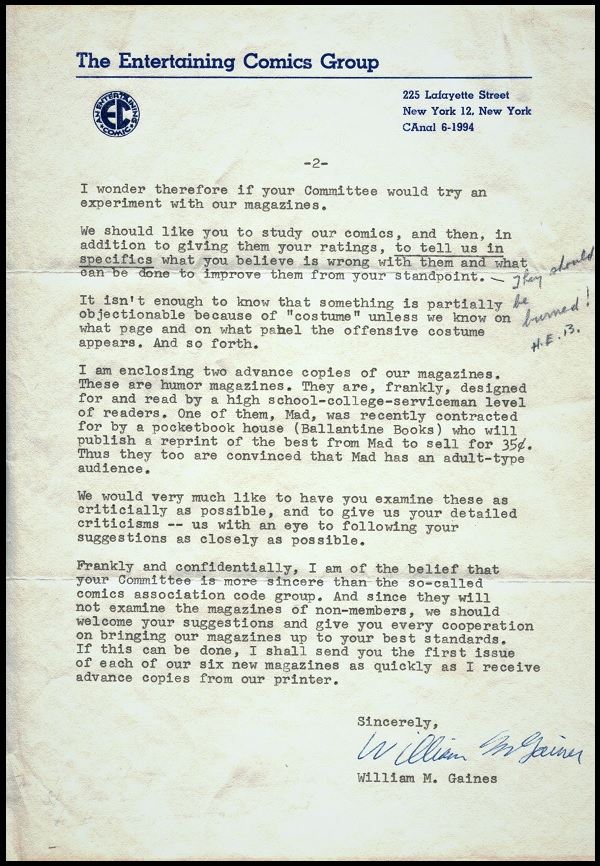

“All of this by way of a preamble to my purpose in writing. Your Committee and I have a common purpose. We want to provide good clean comics for the people who buy ’em and read ’em.”

“I wonder therefore if your Committee would try an experiment with our magazines.”

“We should like you to study our comics, and then, in addition to giving them your ratings, to tell us in specifics what you believe is wrong with them and what can be done to improve them from your standpoint.”

“It isn’t enough to know that something is partially objectionable because of ‘costume’ unless we know on what page and on what panel the offensive costume appears. And so forth.” [Gaines, ibid.]

Gaines included a copy of MAD and PANIC with the letter and informed Murrell that they were “designed for and read by high-school-college-serviceman level of readers.” He asked that the Committee examine the two comics and give him detailed criticisms. His finish by offering the compliment that he felt that “your Committee is more sincere than the so-called comics association code group,” and if Murrell was agreeable to Gaines’ request, he promised to send along copies of future comics as soon as they were available from the printer.

One can only imagine Murrell’s reaction. He likely knew that Gaines was the man who sat in front of the Senate subcommittee and declared one of his comic covers depicting the severed head of a woman as being in “good taste” since it didn’t show blood dripping from her neck.

It was apparent that Gaines was attempting an “end around” the CMAA. There was no love lost between him and the other comic publishers, some of whom viewed him as a nuisance and an embarrassment after his Senate appearance. While the Code had been written to meet the major complaints of comic book critics, it had the beneficial side effect of ridding the industry of its worst offenders and annoyances as well. If Gaines decided to go it alone, nobody would miss him.

In reality, Gaines had little to lose. His offer to the other members of the CMAA to end horror comics if they would end their crime comics, was calculated. He knew that his only “crime” comic, CRIME SUSPENSTORIES, had just ended with the issue currently on the newsstands. Conversely, many of the other publishers had plenty of titles that could fall under the banner of being a “crime” comic. Not just the obvious, such as Lev Gleason’s CRIME DOES NOT PAY, but more benign titles, like DC’s GANGBUSTERS or even its flagship title, DETECTIVE COMICS.

Gaines had nothing to lose by his offer, the others had a lot. He was also aiming for the higher moral ground, hoping to claim that his comics were approved by Murrell’s religion-based committee rather than the corporate code administrators.

Something that Gaines was not aware of was the reception his letter would get from Murrell and the Cincinnati committee. On the letter that Murrell received, someone with the initials “H.E.B” gave their response to Gaines’ proposal. Right next to the paragraph asking, “what can be done to improve them from your standpoint,” the unknown respondent wrote, “they should be burned!”

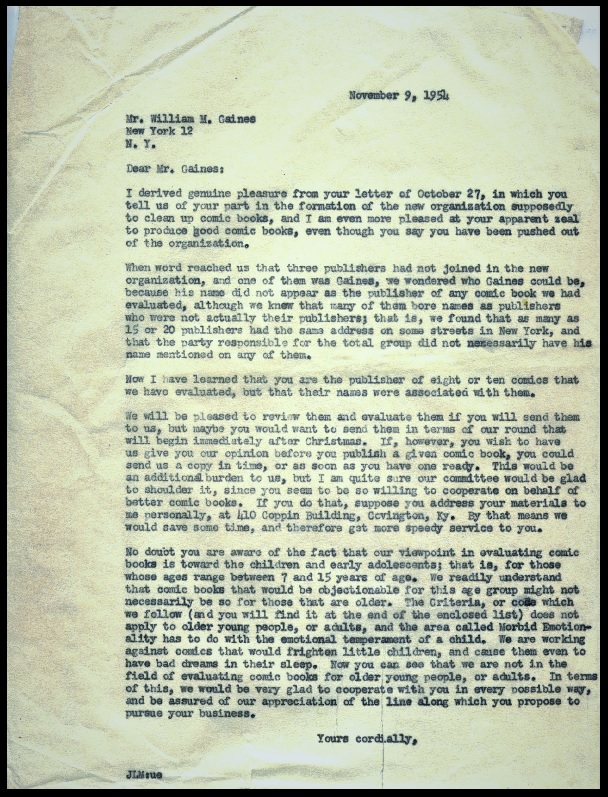

Murrell’s official reply was far more diplomatic.

Letter from Rev. Jesse L. Murrell to William M. Gaines (Nov. 9, 1954)

“I derived genuine pleasure from your letter of October 27,” it began cordially, “ in which you tell us of your part in the formation of the new organization supposedly to clean up comic books, and I am even more pleased at your apparent zeal to produce good comic books, even though you say you have been pushed out of the organization.”

“When word reached us that three publishers had not joined in the new organization, and one of the was Gaines, we wondered who Gaines could be, because his name did not appear as the publisher of any comic book we had evaluated, although we knew that many of them bore names as publishers who were not actually their publishers; that is, we found that as many as 15 or 20 publishers had the same address on some streets in New York, and that the party responsible for the total group did not necessarily have his name mentioned on any of them.”

“Now I have learned that you are the publisher of eight or ten comics that we have evaluated, but that [there were other] names were associated with them.”

Murrell was referring the common tactic used by publishers of using a number of names and “front” businesses on their various comic titles as a way of getting around tax and postal regulations. Many others studying comics who were not aware of this practice were similarly confused.

The minister went on to agree to the “additional burden” of reviewing Gaines’ comics individually, but he cautioned the publisher that the work of the Committee was evaluating comic books “for those whose ages range between 7 and 15 years of age.”

“We readily understand that comic books that would be objectionable for this age group might not necessarily be so for those that are older.”

“Now you can see that we are not in the field of evaluating comic books for older young people, or adults. In terms of this, we would be very glad to cooperate with you in every possible way, and be assured of our appreciation of the line along which you propose to pursue your business.” [Rev. Jesse L. Murrell letter to William M. Gaines, Nov. 9, 1954.]

Murrell’s response must not have been Gaines had hoped for. As much as it pained him, he apparently agreed to join the CMAA and submit his comics to the Comics Code Authority’s oversight. At least, he did so for about a year. The final EC comic with the Comics Code stamp on its cover was INCREDIBLE SCIENCE FICTION #33 (Jan.-Feb. 1956), which appeared on newsstands on Nov. 1, 1955.

On December 15, 1954, the Committee incorporated as a non-profit corporation. While Murrell remained as Chairman, Hildegarde Banner, Ernest Miller, and Charles F. Wheeler were named as trustees.

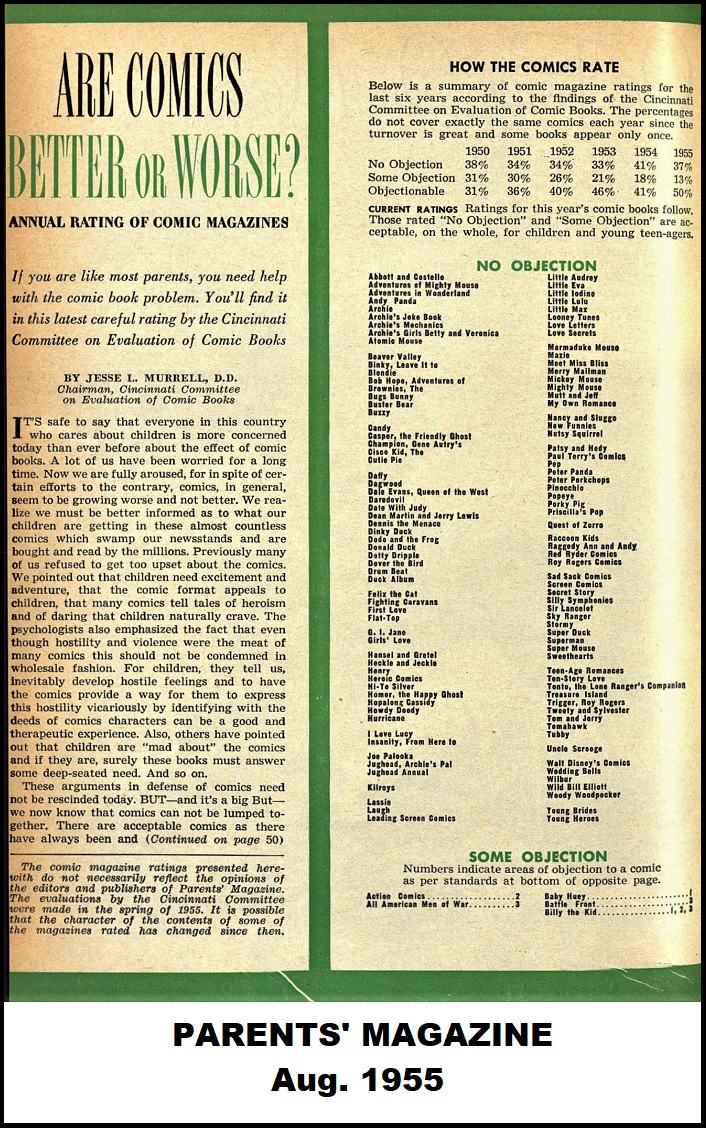

In the August 1955 issue of PARENTS’, Murrell finally acknowledged the Senate hearings of 1954, and quoted from its conclusion that, “The welfare of this nation’s young makes it mandatory that all concerned unite in supporting sincere efforts of the comics industry to raise the standards of its products and in demanding adequate standards of decency and good taste…Continuing vigilance is essential in sustaining this effort.”

PARENTS’ MAGAZINE (Aug. 1955)

“It is here that the Cincinnati Committee on Evaluation of the Comic Books offers help.” [Murrell, Jesse L., “Are Comics Better Or Worse?” PARENTS’, August 1955.]

The remainder of the article is self-congratulatory, with Murrell citing how the efforts of the Committee have received positive reactions from all over.

“The mail runs high and requests range all the way from those for single copies of the list of evaluated comic books to pleas from near and far for speakers and resource persons. The flood of mail comes from the entire English speaking world.” [“Are Comics,” ibid.]

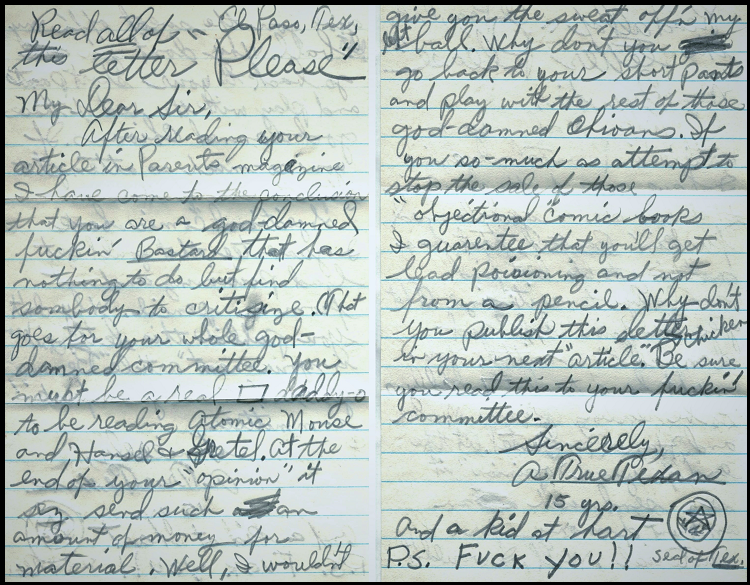

As is always true, though, you cannot please everybody. One example came in the form of an anonymous letter sent to the Committee from El Paso, Texas in August 1955. In a profanity-lace diatribe filled with misspellings, the letter-writer preceded to call Murrell and “the rest of those god-damned Ohioans” every vulgar name he/she could. In a final show of state pride, the author signed the missive: “A True Texan, 15 yrs. And a kid at hart [sic]” [Anonymous letter to Jesse L. Murrell, Aug. 8, 1955.]

Hate letter from anonymous writer to the Committee (Aug. 8, 1955)

By 1956, the bloom was off the rose. While the Committee was still frequently cited and used by late-to-the-party groups concerned about the comics coming out with the Comics Code approval, essentially its goals had been achieved.

The 1956 rating that appeared in PARENTS’ magazine was written by Charles F. Wheeler, a trustee of the Committee and an English professor at Xavier University. Murrell, who was now in his late 60s, well above retirement age, was not even mentioned in Wheeler’s list summary. Unsurprisingly, of the 203 comics reviewed, only 50, less than 25%, fell into the “objectionable” category.

“A letter from Parents’ Magazine in 1957, answering one from the Committee that it would not be making a complete evaluation of the comic books that year for the reason that the quality of printed matter carried in the comic magazines had improved, brought a reply embodying the following observation: ‘We have considered your last letter for several weeks now and have finally decided that the Committee on Evaluation of Comic Books has done such a good job that it has practically put itself out of work. The comics are certainly much better now than when the Committee was first created.’” [Murrell, “The Greater Cincinnati Committee,” op. cit.]

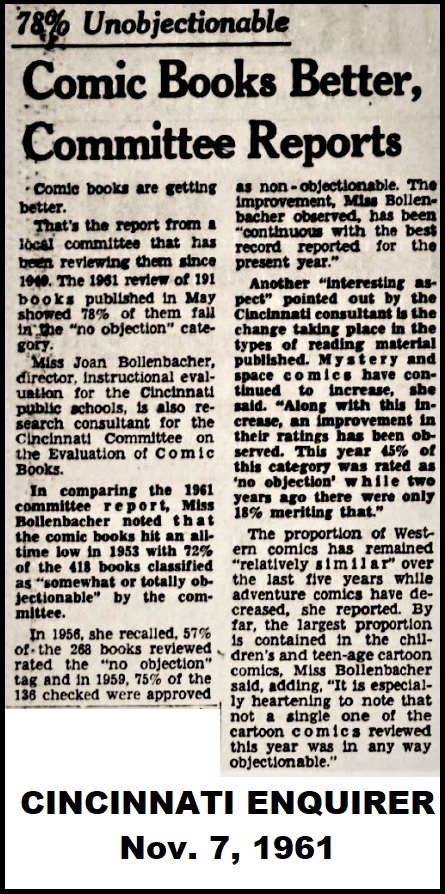

The Cincinnati Committee on the Evaluation of Comic Books formally stopped reviewing comics in 1960. Thereafter, it would occasionally evaluate comics intermittently, as it did in November 1961, when they determined that 78% of the comic books for sale were unobjectionable. The Committee finally disbanded in April 1979.

CINCINNATI ENQUIRER (Nov. 7, 1961)