New York City Board of Education books illustrated by students (1946-1948)

©2019 Ken Quattro

New Yorkers like to claim that it’s their water that makes their pizza and bagels taste better than anywhere else. I’m not about to get into that debate, but I will say there must be something in their environment that produces comic creators.

Of course, the proximity of the comic book industry to the NYC schools has much to do with it. But you can’t overlook the quality of talent that has come out of the high schools. This wasn’t by accident.

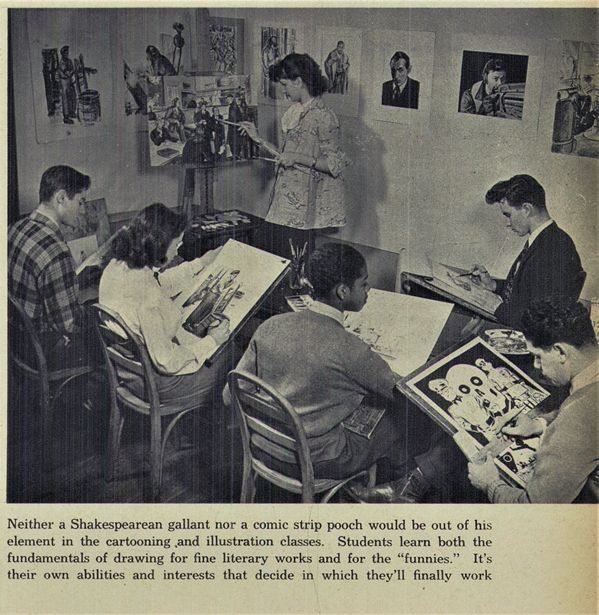

For many years, New York City has maintained magnet schools dedicated to recruiting and teaching students drawn from all five boroughs with an aptitude in the various arts—music, dance, drama and the fine arts. Among these was the High School of Industrial Art (SIA), which a bit more pragmatic approach to their approach.

“It has developed an educational program designed to train people to put beauty into utilitarianism…a practical program of applied commercial art that reaches right into your home.” [“High School for Bread ‘N Butter Artists,” SEVENTEEN, (March 1946)]

This job-oriented curriculum made sense, as the school was founded in 1937, right in the midst of the Great Depression. Teaching a youngster to draw was a worthy goal. Teaching them how to turn that talent into a paying occupation was even better.

Getting into SIA or any of the other magnet schools was no easy task.

“They take an intelligence test and a general knowledge test (successful industrial artists must have more than skilled fingers). They they make a quick drawing on an assigned subject. No one expects those drawings to look like the work of finished artists (most entrants haven’t had any previous art training at all), but they are expected to show innate talent.”

“The tests are weighed together with portfolios of the applicants’ past work and with previous school records. Finally the weeding process is completed. And a new class of SIA students is started on its way.” [Ibid.]

At the time, in 1946, males students outnumbered the female students two to one. Yet, at SIA they didn’t restrict the girls in any way.

“Until recently, too many [female students] felt that all they could do was strictly ‘woman’s work’…fashion illustrating, dress designing and the like. But employer after employer has made it clear that he’ll buy the services of good draftsmen, good photographers, good silk-screen printers…men or women. The only criterion…at long last…is beginning to be ability.” [Ibid.]

School of Industrial Art cartooning class, SEVENTEEN (March 1946)

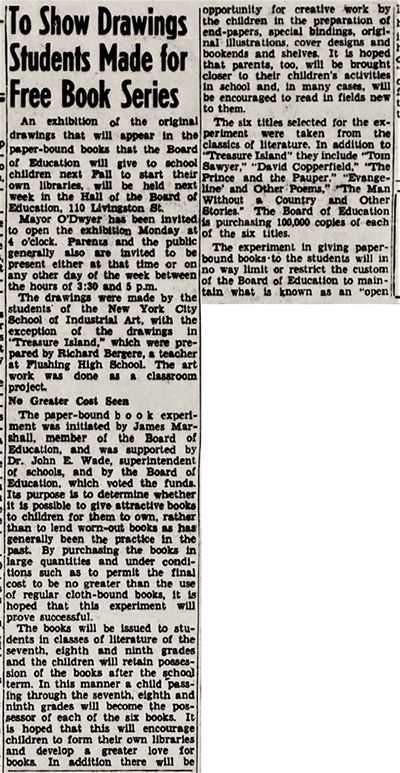

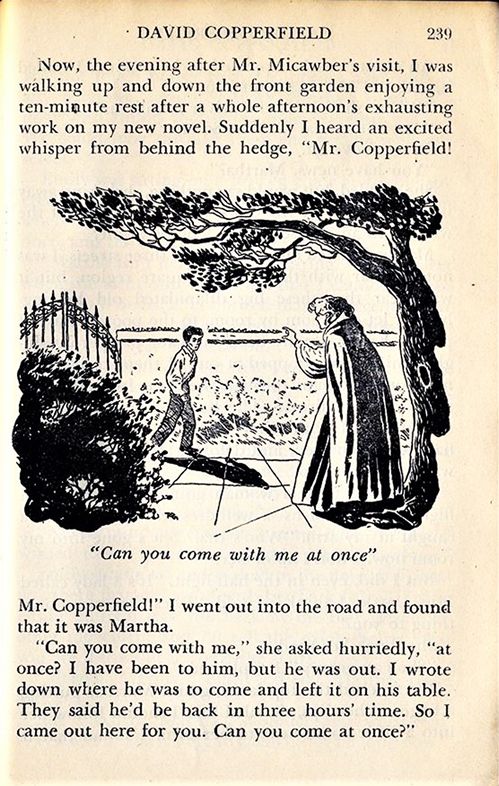

In the summer of 1945, a new initiative was rolled out by the New York City Board of Education with almost no fanfare.

“We are pleased to see that the Board of Education is distributing free copies of the classics to New York City’s school children. We agree wholeheartedly with the Mayor’s description of good reading as ‘calisthenics of the brain’…” [“Is the Mayor Willing?,” BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, July 15, 1945.]

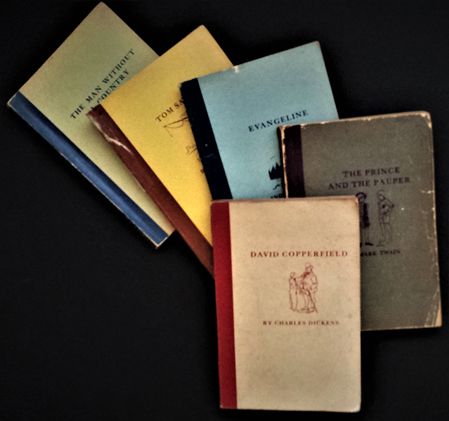

The idea was to create a series of small, (4 1/4″ x 6 3/8″) paper-bound books, reprinting classics of Western literature, were to be given to junior high students as a means of starting their own libraries. So enthused about the program was Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, that he wrote the preface to the TOM SAWYER edition of the series.

And to include the students in the publication of the books themselves, it was determined that five of the six books in the series would be illustrated by young artists from the School of Industrial Art.

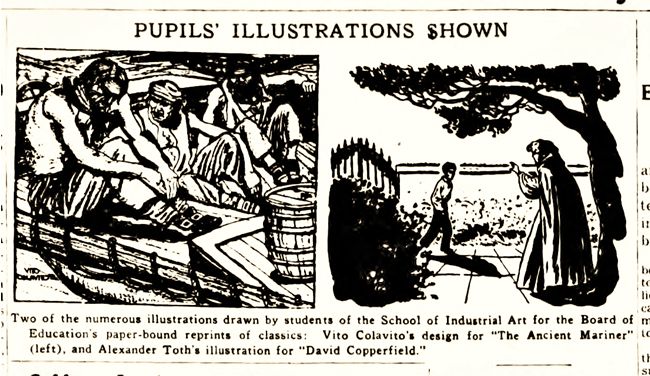

BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE (May 31, 1946)

The five classics that were to be illustrated by the students were TOM SAWYER, DAVID COPPERFIELD, EVANGELINE AND OTHER POEMS, THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER, and THE MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY AND OTHER STORIES. The sixth book was TREASURE ISLAND and that was illustrated by a teacher from Flushing High.

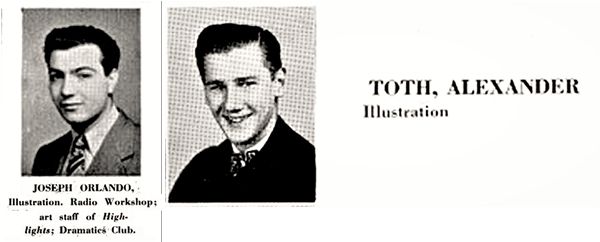

The students chosen to draw for the books were among the best artists in the school. They would go onto careers in various fields, but three of the chosen were names that became familiar to comic book fans: Alexander Toth, Joseph Orlando and Jacob Katz.

Alex Toth (1946) and Joe Orlando (1945) SIA yearbook photos

Jacob “Jack” Katz avoided his senior photo, listed in the 1946 SIA yearbook as “camera shy.”

NEW YORK SUN article illustration with Alex Toth artwork (June 3, 1946)

NEW YORK SUN (June 3, 1946)

Even before the books were published, an exhibition of the original artwork appearing in them was displayed the week of June 3, 1946, at the Board of Education building. To commemorate the event, officials from the school board, the Brooklyn Library system and even newly-elected Mayor William O’Dwyer attended the opening.

The books were printed by Carey Press Corp., which was owned by William H. Friedman, who also happened to be a commissioner of the New York City Tunnel Authority and a political appointee of outgoing mayor LaGuardia. If any questions of impropriety were raised about a city official having a contract to print books for the city, none were mentioned in news reports.

The future comic book pros were represented well in the series. At least one of them had an illustration in each book. Alex Toth had work in DAVID COPPERFIELD and THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER, Joe Orlando’s drawings appeared in THE MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY AND OTHER STORIES, THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER and TOM SAWYER and Jack Katz was the most prolific, with illustrations in EVANGELINE, THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER and DAVID COPPERFIELD.

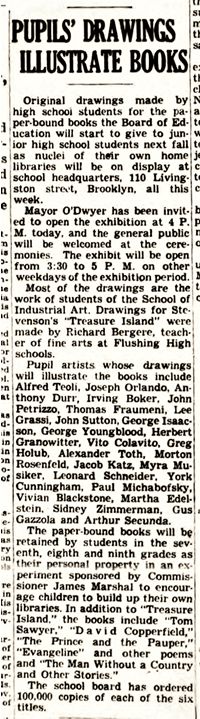

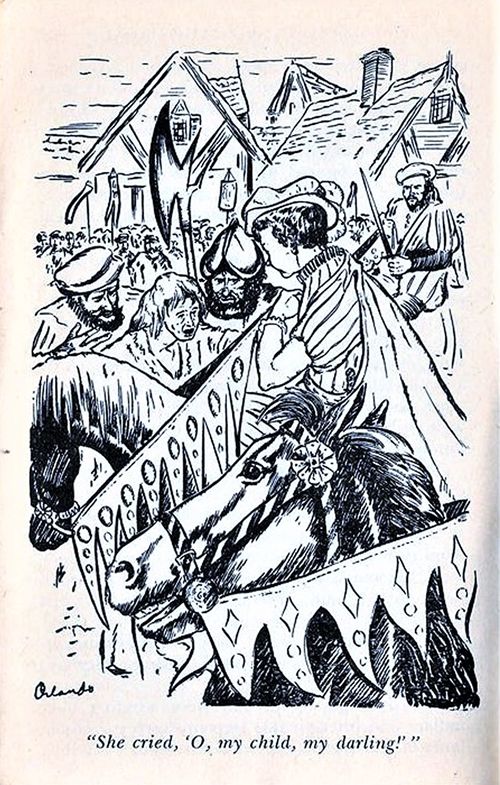

Alex Toth PRINCE AND THE PAUPER illustration

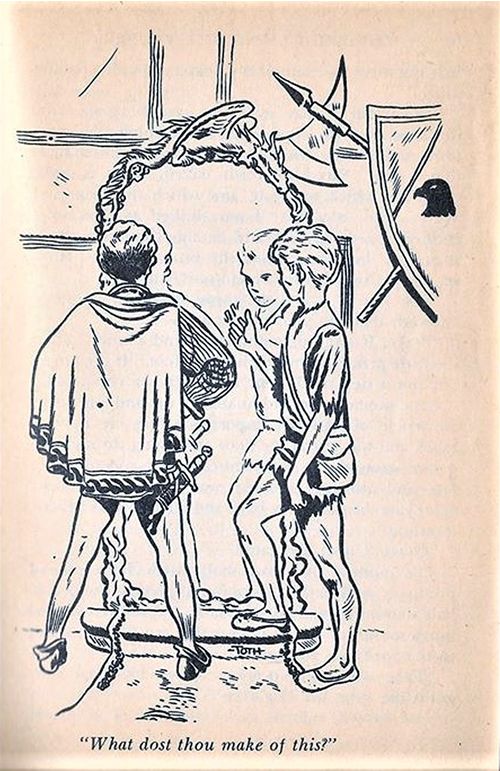

Alex Toth DAVID COPPERFIELD illustration

Joe Orlando PRINCE AND THE PAUPER illustration

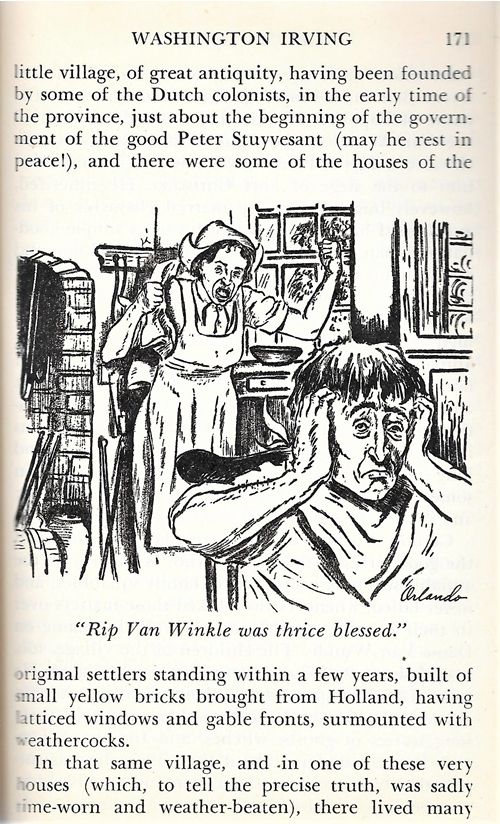

Joe Orlando “Rip Van Winkle” illustration from MAN WITHOUT A COUNTRY AND OTHER STORIES

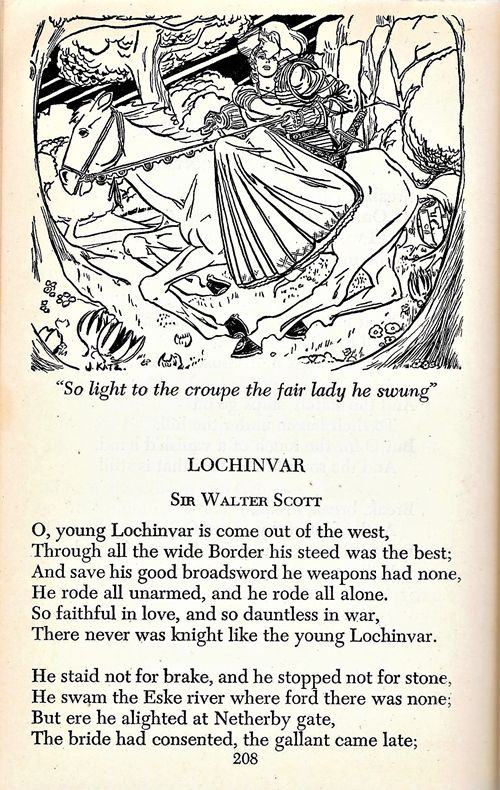

Jack Katz “Lochinvar” illustration from EVANGELINE AND OTHER POEMS

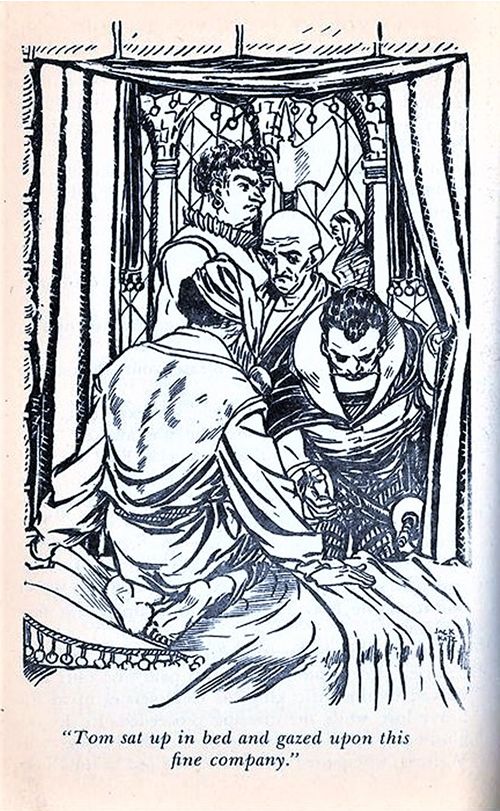

Jack Katz PRINCE AND THE PAUPER illustration

The book series was a hit with both teachers and students and their distribution garnered them coverage in the local newspaper. Of course, the article’s writer couldn’t help but take a side-swipe at the lowly comic book as he touted the classics series.

BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE (Nov. 3, 1946)

“Comic books and their ilk, which have been attacked in some quarters for their influence on youngsters, have come up against some fair competition at John J. Pershing Junior High School.”

“George Goldberg, chairman of the English department, has been pleasantly surprised by the enthusiasm expressed by the pupils. A sampling of sentiment on the part of the children shows in most cases a pride of ownership in books.”

“William Saparito, for instance, remarked, ‘It’s nice to have a book to keep so we can start our own libraries.'”

“‘They’re a good size and easy to carry around.'”

“‘I read mine and passed in on to my sister.'”

“‘I lent mine to a friend.'”

“‘I like the idea of having a book of poems of my own.'” [“Students Like Books Mates Illustrated,” BROOKLYN DAILY NEWS, Nov. 3, 1946.]

The series was successful enough to go into at least three editions, the last in 1948. If one of the reasons for the creation of the book series was to provide students with a literary alternative to comics, then there was an irony attached to that belief likely nobody realized.

By the time the books were first distributed in 1946, Jack Katz and schoolmate Carmine Infantino had drawn at least one story for CAPTAIN AERO and Alex Toth had already been a working comic book artist for over a year.

1 Comment ?>

This is a great article!! Great find, great research!! Do you have any scans of the David Copperfield work that Jack Katz did ?