© 2021 Ken Quattro

Jimmy Jemail had been the “Inquiring Fotographer” for the NEW YORK DAILY NEWS since 1921 and would be for several decades more when on June 14, 1947, he posed his question of the day to any likely female he encountered along the Avenue of the Americas.

Marion Helen McDermott

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

June 14, 1947

“A widow, bemoaning her inability to find a husband, exclaimed, ‘The best men are married!’ Are they?”

As expected,the answers Jemail received were varied and undoubtedly reflective of each woman’s personal experience. One respondent was a smiling young woman, with a wide face and long Veronica Lake-style hair that cascaded around her shoulders.

“No, that isn’t true,” began Marion McDermott’s response, “not in the 28-35 age bracket. Many veterans have gone back to school and cannot afford to get married. Most of them are the finest marital prospects if they could only be fortunate enough in finding women as fine as themselves.” [Jemail, Jimmy, “The Inquiring Fotographer,” NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, June 14, 1947.]

Marion was a native Californian, born in San Francisco on March 8, 1923, and Irish-American on both sides. Anita McFarlane married Francis J. McDermott back in 1921 and the young family had moved east to New York City when he was offered a job as the General Sales Manager of Julius Schmid, Inc., one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of condoms.

Francis’ position had provided the family a home in Forest Hills out on Long Island and a comfortable living during the depths of the Great Depression. Comfortable enough that they enjoyed a membership in the Westbury Beach Club, a live-in maid, and Marion could attend an all-girls Catholic high school, The Mary Louis Academy.

The academy offered a college prep curriculum to its students, some of whom went on to convents and a life as a nun, while others prepared for acceptable female careers as secretaries or teachers. Upon her graduation in June 1941, at which Marion gave an address entitled “The Lady with the Lamp,” she was awarded a scholarship to a secretarial school. Whether or not Marion used that scholarship is not known. However, she did attend the private Catholic College of New Rochelle, where she received a degree in economics.

THE TABLET

Sept. 11, 1937

After college, Marion took a position working for the NEW YORK TIMES as a news analyst and synopsis writer. It was not what her degree had prepared her for, but it was a step above the secretarial pool. As exciting this opportunity must have been for her, it would be Marion’s next job that would utilize all her talents.

Archer St. John

[photo courtesy of Shaun Clancy]

St. John had a solid, middle-class upbringing in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. Born in 1904, Archer and his two siblings enjoyed the privileges of living in the tony community, albeit from the lower end of the economic spectrum that defined the town. His father Joseph was a chemist, a pharmacist in today’s parlance, who owned two drugstores, while his mother Amy had given up her profession as a nurse to raise Archer, his sister Dorothy and his older brother, Robert.

Amy returned to nursing when her husband died i 1917 and even though she lost the drugstores as a result of his death, she still earned enough to send Archer to a private Episcopal school. In the early 1920s, Archer and Robert both became journalists; Robert at the CICERO TRIBUNE, while Archer started his own newspaper, the BERWYN TRIBUNE. They quickly became known for their critical editorials and exposés of local governmental corruption and the role gangsters played in it.

In particular, the brothers gained the enmity of mobster, Al Capone. Capone had headquartered his criminal operations in Cicero, placing him in the direct sight of the St. John brothers and they were in his. His interference in local politics had been the focus of particular scrutiny by the brothers, until finally, Capone had enough.

On April 6, 1925, Robert St. John was attacked and beaten in broad daylight by members of the Capone gang. Meanwhile, Archer was picked up by other members of the gang and “taken for a ride.” Contemporaneous accounts varied wildy–some early reports claimed he had been shot–but in the end, Archer was found hours later, wandering the streets and badly beaten.

CHICAGO HERALD TRIBUNE

April 7, 1925

After the attack, Capone purchased the CICERO TRIBUNE and Robert St. John lost his job. He joined Archer at the Berwyn paper where they struggled to keep the small newspaper operating in the face of financial difficulties.

“Archer was a good businessman, but it was a shoestring operation. Had we had a thousand dollars of backing we might have achieved some degree of financial success, or at least would not have been harassed six days a week by the pressure of collecting amounts in order to pay bills. But we had no capital and hod to go to extremes to keep our creditors from closing us out.” [St. John, Robert, THIS WAS MY WORLD, pp. 199-200, (1953)]

In their off-hours from their newspaper endeavors, Archer and Robert occasionally acted in local plays. It was likely while performing in one of these plays that Archer met Gertrude Faye Adams.

Gertrude was originally from Muskegee, Oklahoma, born in 1896 before it became a state, and was the daughter of one of that town’s leading citizens, Milo E. Adams. Milo was the owner of a large cigar store and billiard parlor which made him wealthy and garnered him much favorable hometown press. He even sold his own brand of cigars, one of which he named the “Gertrude- Fay” after his daughter.

Gertrude Faye Adams

c. 1922

Milo’s world came crashing down, however, when in 1910 he was found to be having an affair with a 20 year-old woman in Tulsa. The seamy details of the scandal played out in the local newspapers and ultimately led to the divorce of Gertrude’s parents. Nonetheless, the settlement from the divorce gave wife Martha Adams full custody of their four children, the family home and ownership of the cigar company. Milo married his young sweetheart, but that marriage, too, ended in divorce.

Financially secure, Martha Adams and her children frequently appeared on the Muskegee society pages. While partly due to their prominence in the city, the fact that Martha was also the society page editor of the MUSKEGEE PHOENIX certainly helped.

In November 1912, Martha remarried. Her new husband was Wilberforce “Jerry” Rand, the former state editor of the PHOENIX. In 1914, Gertrude was sent away to attend her final two years of high school in Chicago at Bowen Preparatory. Upon graduation in June 1916, she studied art in that city under John Singer Sargent, but her main interest was acting. To further her study of that art, she attended the Anna Morgan Studios, housed in the historic Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue.

Gertrude returned to Oklahoma in 1921 and brought what she had learned from Anna Morgan back with her. She performed in local productions and began offering classes in “Expression and Dramatic Art” out of her home.

OKMULGEE DAILY TIMES

Sept. 10, 1921

By this time, Gertrude had added an “e” to the end of her middle name, giving it a sophisticated flair. The young actress moved to New York City in a likely attempt at furthering her acting career, did some modeling and after about a year, returned to her home state. That stay, too, was short-lived, as she moved once again, back to Chicago. This move proved to be life-changing.

“Often, early in the week when we had no deadlines forcing us to stay up all night, Archer and I would go off for an evening in Chicago’s Near North Side and forget pay-roll and publication problems by taking part in semi-professional plays.”

“The ‘Little Theater’ was run by two girls, the Udell sisters, and their blind mother, who had rented a store on North Clark Street in the rear of which they had built a stage. There they put on plays of an eclectic nature, interspersed with a few classics and some Broadway plays that had never come to Chicago.” [St. John, pg. 202]

The St. John brothers joined the Studio Players in their Little Theater productions performed in the converted storefront at 826 N. Clark Street. It is likely there that Archer met Gertrude while both were performing in one of these plays.

By 1927, the BERWYN TRIBUNE’s financial troubles became too burdensome and it soon closed. Robert accepted a job as managing editor of a Rutland, Vermont newspaper, while Archer married Gertrude, had a son and became advertising manager for Lionel Trains.

Archer’s new position necessitated a move across country to the New York City area, where the young family settled in Noroton, Connecticut, a tiny village abutting Darien. Their new home was located in affluent Fairfield County, where, despite the long commute into Manhattan, many business executives resided.

Even while the world was suffering the crippling effects of the Great Depression, the St. John’s were prospering. Throughout the 1930s, both Archer and Gertrude were socially active in their community. Archer with the Boy Scouts and Gertrude involved in numerous activities at St. Matthews Episcopal Church. She even sang solos in front of the congregation at Christmas time.

Later in the decade, they moved to Wilton, another exclusive enclave located even further from the big city. The family appeared frequently on the society page; even though Gertrude was now always referred to as “Mrs. Archer St. John,” having surrendered her own first name according to the custom of the era.

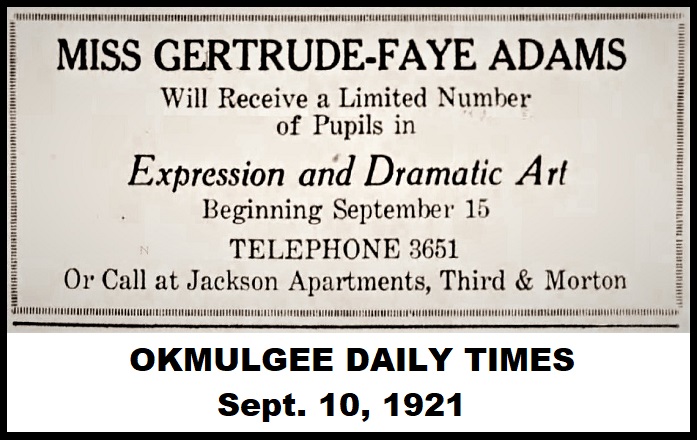

AIR NEWS vol. 1 #1

May 1941

When WWII broke out, both St. Johns patriotically volunteered to be enemy airplane spotters in March 1942. It was a task for which Archer was particularly well-suited. He had recently left his high-paying advertising position at Lionel to begin his own publishing venture, AIR NEWS magazine, an aviation oriented publication which hit the newsstands with its first issue in May 1941.

Archer’s interest in AIR NEWS did not last, though, as he soon turned the magazine over to its editor, Phillip Andrews. It was a curious transaction, described during a later Senate investigation of the National Defense Program.

“It was owned by Archer St. John, and it was not making any money. Mr. St. John decided to discontinue it and gave it to Mr. Andrews as a property.” [Investigation of the National Defense Program. 78th Congress. 10423. (1944) (testimony of Edward Lefler).]

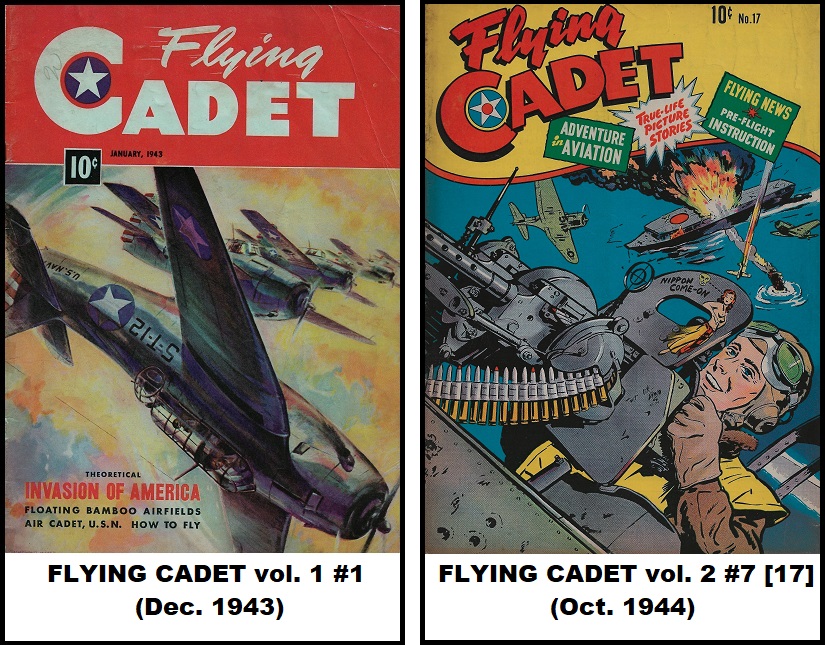

However, Archer did not leave publishing. Late in 1942, the first issue of his latest venture was released. It was titled FLYING CADET and like AIR NEWS, it was aimed at aviation devotees.

FLYING CADET was a unique hybrid: part photo magazine, part comic book. Archer, who was listed as its editor, stated in its debut issue that the publication was aimed at “young men, between the ages of 15 and 19, [giving them] accurate and clarified information that will be helpful to them in preparing themselves for aviation careers.” [St. John, Archer, FLYING CADET vol. 1 #1 (Jan. 1943).]

FLYING CADET vol. 1 #1 (Dec. 1943) and FLYING CADET vol. 2 #7 [17] (Oct. 1944)

While the black and white photos constituted most of the content, each issue contained a short comic book section drawn by noted illustrator L.Meinrad Mayer provided instructional information to its readers. FLYING CADET continued using this format until its final issue–FLYING CADET #17 (Oct. 1944)–when it suddenly eschewed much of its photographic material and became more readily identifiable as a comic book.

Notable as well was the owners statement on the last page of this issue. Archer was now listed as the publisher, but that didn’t tell the entire story. .

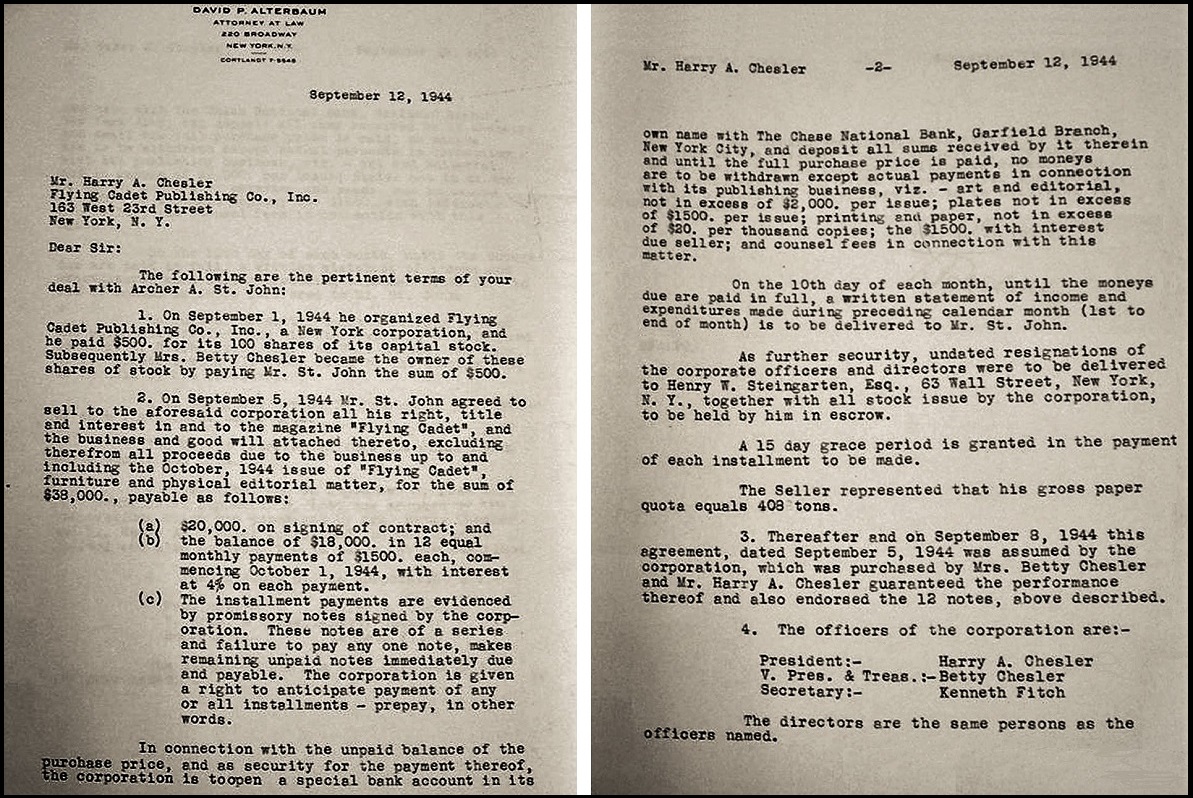

Even though the owner’s statement in FLYING CADET #17 (Oct. 1944) names St. John as editor, business manager and owner, by the time it was published on October 1, 1944, he had already assigned the copyright to Harry ‘A’ Chesler on September 8th of that year.

A letter dated September 12, 1944, notes that on September 1st, St. John organized the Flying Cadet Publishing Company, Inc., paying $500 for its 100 shares of capital stock. In turn, St. John sold those shares to Betty Chesler (Harry’s wife) for the sum of $500. Subsequently, St. John then sold, “…all his right, title and interest in and to,” the subsequent corporation owned by Chesler. Given these facts,it is a fair assumption that this influx of cash helped finance the start up of St. John’s comic publishing company a few years later.

Harry ‘A’ Chesler agreement with Archer St. John

Sept. 12, 1944

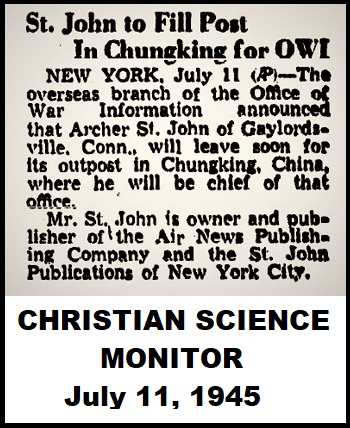

But before he embarked upon that next venture, Archer had a duty to perform. Even though he was not draft eligible due to his age and marital status, he took a position with the Office of War Information (OWI) to do his part to help with the war effort.

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

July 11, 1945

“The Overseas Branch of the OWI announced today that Archer St.. John of Gaylordsville, Conn., will leave soon for its outpost in Chungking, China, where he will be chief of that office.” [“Connecticut Man Gets OWI Post in Chungking,” CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR, July 11, 1945.]

Archer returned from overseas by the end of October 1945, and that same month, his mother died. Although he apparently had money of his own, he also likely received an inheritance from her estate. In any case, a little more than a year after his return, the first comic books from St. John Publishing began to appear.

The initial releases entitled COMICS REVUE and A TREASURY OF COMICS were anthologies of reprinted newspaper comic strips. Similar reprint titles would soon follow. It would be about a year or so before any St. John comics carried original material and although Archer apparently acted as editor in the beginning, he needed help if he was to compete.

COMICS REVUE #1

(1947)

Archer took a multi-faceted approach to producing his comic book line. Along with the continued practice of using reprinted comic strips, he hired the team of Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer, who packaged THE THREE STOOGES and several other titles for him in their own studio. Moonlighting animators from Paul Terry’s New Rochelle-based studio produced MIGHTY MOUSE and TERRYTOONS comics, Gladys Parker contributed with the comic book version of MOPSY and reused Chesler shop reprints filled out issues of AUTHENTIC POLICE CASES.

It made for an eclectic, if somewhat chaotic, line of comics. St. John comics had no identity of their own. This must have occurred to the savvy publisher, who was surely aware that he had to make a splash with the look of his comics if he wanted them to stand out on the very crowded newsstands. To this end, Archer went and hired the most-copied cover artist of the time, Matt Baker.

To this point in 1948, Baker had worked exclusively through the Jerry Iger shop. His covers for the various Fiction House and Fox titles the shop produced were stunning eye-catchers. The almost always featured a comely young woman, provocatively posed and scantily clad. The sexual lure worked, as the pubescent male readership coveted by publishers lusted mightily after these comics and they sold in the millions. Other artists tried to follow suit, but Baker was at the head of the pack, and he was now working for Archer St. John.

Michael A. St. John

1948

Meanwhile, there were personal changes in Archer’s life as well. His son, Michael Archer St. John, was attending Staunton Military Academy in Virginia, and eventually the family bought a historic estate a few hours away in Mount Holly, Virginia named Bushfield.

The estate contained a small farm and the urban-dwelling St. John family needed help to run it. They ran ads in the local newspapers looking to hire a “farmer and wife, white or colored, middle-age,” for a combined wage of $120 per month.

As a result of this move, Archer maintained two homes. Part of his time at Bushfield and part of his time at the New York Athletic Club when he had business in the city. He was a member of the club and it would be the address he used frequently over the next few years.

It was around this time that Marion McDermott began working for St. John.

Although she apparently had no experience in comic book editing, Archer evidently saw something in the young woman. He assigned her the editorship of his new romance comics line. It seems he had a penchant for hiring young women for editorial positions, as McDermott was not the only one.

In 1952, Archer expanded his publishing company to include digest-sized magazines. First out was MANHUNT, a detective magazine that would eventually become legendary for its cast of great crime writers. To edit this new venture, Archer hired a 24 year-old woman who signed herself as “E.A.Tulman,” to hide her feminine first name of Eleanor.

“Miss Tulman attributes her success to hard work and an understanding boss (publisher Archer St. John who thinks young people with ability should get the breaks.)” [“Girl, 24, Edits New Detective Story Magazine,” SANTA MARIA TIMES, Feb. 24, 1953.]

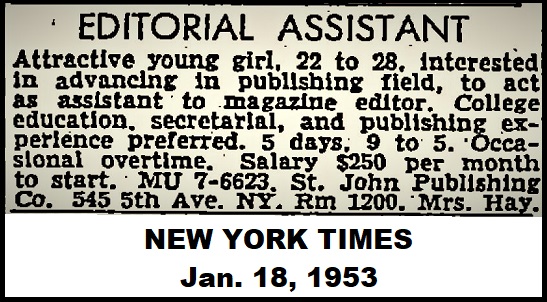

NEW YORK TIMES

Jan. 18, 1953

Archer, it seems, required a specific type. A classified ad that ran in early 1953, stated among its requirements for Editorial Assistant, that the candidate should be an “Attractive young girl, 22 to 28, interested in advancing in the publishing field, to act as assistant to magazine editor. College education, secretarial, and publishing experience preferred.” [“Editorial Assistant,” classified ad, NEW YORK TIMES, Jan. 8, 1953.]

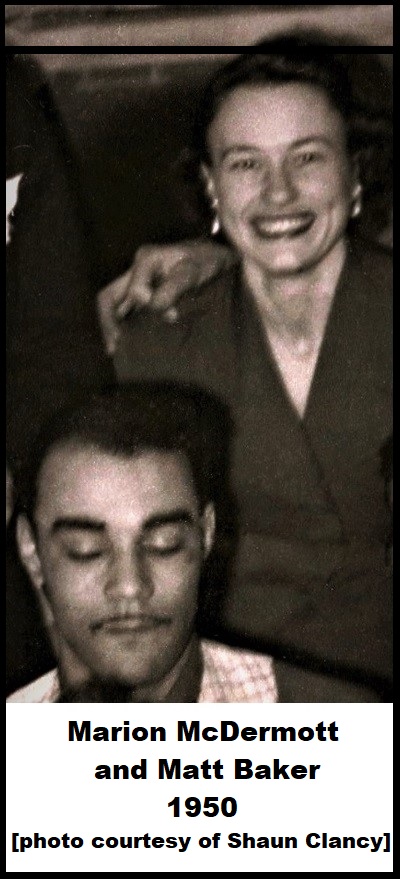

Marion McDermott and Matt Baker

1950

[photo courtesy of Shaun Clancy]

Marion certainly fit the mold and she was more than capable of handling her new job.

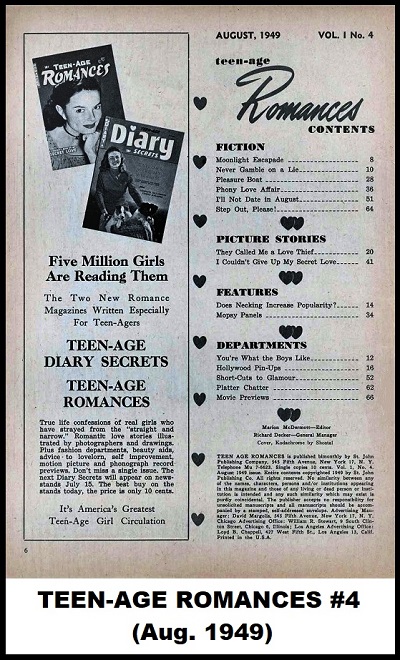

Marion took over editing of the romance comics right at or very near their introduction. She is named on the contents page of several early issues of TEEN-AGE ROMANCES and DIARY SECRETS in 1949. Later, she is seen in a photograph taken at the company’s 1950 Christmas party standing right behind Matt Baker, the only woman in the group.

Whether it was per her request or just happenstance, Marion ended up with Baker as her primary artist and she used him with great success.

Baker began working on St. John’s romance comics with TEEN-AGE ROMANCES #1 (Jan. 1949). These comics required Baker to restrain his natural tendency to use cheesecake poses flaunting the bodies of women. He was now appealing to a female readership and was tasked with depicting women more realistically, with less focus on suggestive posturing and more emphasis on emotion. Baker blossomed while working for Marion. His work became more illustrative and his eye for fashion and design resulted in covers that are masterpieces of comic book art.

TEEN-AGE ROMANCES #4

(Aug. 1949)

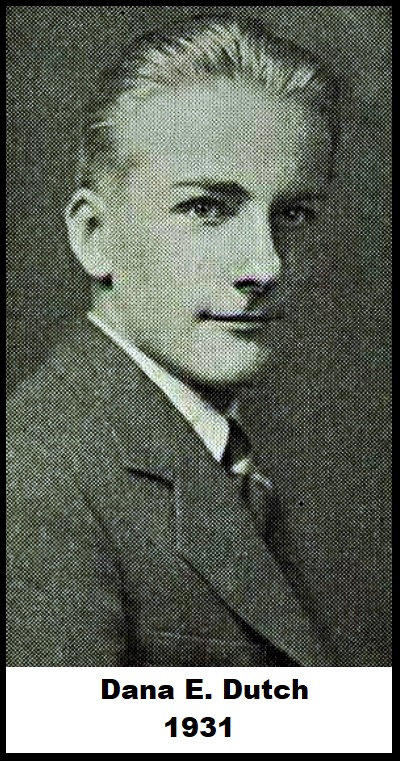

Along with Baker, Marion also had the writing talents of Dana Erskine Dutch to utilize. Dutch was born in 1912 and hailed from Newton, Massachusetts. He had been a writer and editor in the Harry ‘A’ Chesler shop before coming over to St. John and he would prove to be a valuable and prolific asset to the company.

Dutch had deep New England roots and spoke with an thick Boston accent. Educated at Columbia University, Dutch had entered the comic book industry in the early 1940s when his journalistic career stalled. His scripts for the St. John romance comics were notable for their portrayal of strong, independent women, likely reflecting Marion’s influence as his editor.

However, Marion’s tenure as editor was not without controversy. Irwin Stein was also an editor for St. John and his editorship overlapped with that of Marion. He later characterized her role in the romance comics as minimal and steeped in office gossip.

Dana E. Dutch

1931

“…she prepared the first [DIARY SECRETS], and then I actually saw it to press,” Stein told interviewer John Benson.

“Archer and Marion McDermott had been having an affair. And Mrs. St. John, whose name I never knew, found out about it.”

“I had run an ad in the Sunday Times, and Saturday night I got a phone call from Archer, saying, come in Monday morning. He hired me on the spot.” [Benson, John, CONFESSIONS, ROMANCES, SECRETS AND TEMPTATIONS, pp.9-10, (2007)]

Stein implied to Benson that Marion had stopped working for St. John at that point and he was dismissive of any role she played in the company afterward.

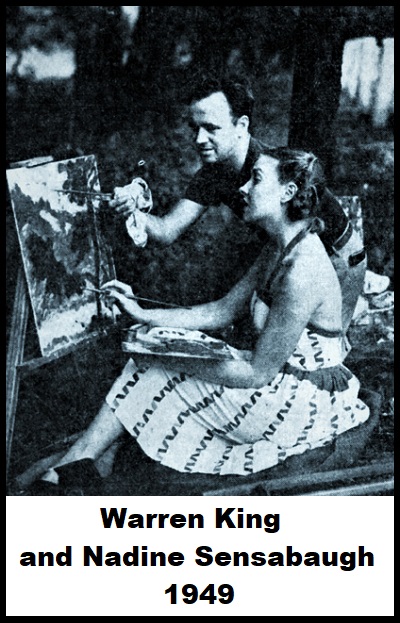

Stein’s remembrances coincided in some details with those of Nadine King, but differed in others.

King, née Sensabaugh, began working for St. John when he was just beginning the expansion of his comic book line and she was working as his secretary when Marion was hired. When asked by Benson whether or not Marion was “a true editor,” King replied:

“Yes she was. Of course.”

“She came there for a job and St. John hired her. She worked on all the magazines. And then when Nugget was in its embryonic stages, she was very involved with that.” [Benson, 25.]

Warren King and Nadine Sensabaugh

1949

Benson also interviewed artist Warren Kremer, who also had a more positive view of Marion’s editorial input than did Stein.

“…she was always in on the discussions, in with [Archer] St. John when I was there. I can’t remember what she was, whether she was his secretary, or whether she was his top editor, or what. But she was very close to him, I know that. And, of course, you hear other things.” [Benson, 33.]

It was those “other things” that creep up again and again in memories of Marion. In a personal letter to the author, artist Lily Renée Phillips, who worked as a freelancer for St. John, gave her impressions of both Marion and Archer.

“Archer St. John was a very nice man, I liked him but he liked me a little too much.”

“I thought Marion was an efficient editor and [she] later became Archer’s girlfriend.” [Phillips, Lily Renée, letter to the author, April 4, 2007.]

And yet another freelancing artist, Ric Estrada, remembered Marion with fondness and perhaps from the viewpoint of a young man with a crush.

“She was a very attractive woman, perhaps a little older than me. She was perhaps in her late twenties or even early thirties. Very attractive, very good looking, and, you know, there was a mutual admiration. I think she knew I admired her for her looks and her intelligence…”

“…I remember her as having green eyes and a very languorous smile, and a very sensitive voice.”

“…I saw that she exuded a sort of a quiet subdued eroticism toward every man. She was a lovely woman.”

“…one of the reasons I remember Marion McDermott so fondly [is] because she encouraged my style. She was encouraging in my trying these black-and-white patterns, and so on. She didn’t criticize me negatively; on the contrary, she said, ‘Oh, this looks wonderful; this is very strong. Can you do more of this?’ And I felt encouraged to develop a certain style which otherwise I might not have. She was a great encouragement in my career.” [Benson, 59-61.]

Perhaps it was inevitable, but the rumored affair between Marion and Archer hangs over every memory of her. While Stein repeated details of hotel assignations and was generally dismissive of Marion’s editorial input, most others who worked with her admired her professionalism and viewed the affair as unfortunate.

As noted, Archer apparently preferred a specific type of female employee. Young, attractive, college-educated. Marion was much younger than him. In 1949, she was only 26 years old, while he was 19 years older. And it should be noted that his wife Gertrude was eight years older than him and 27 years older than Marion.

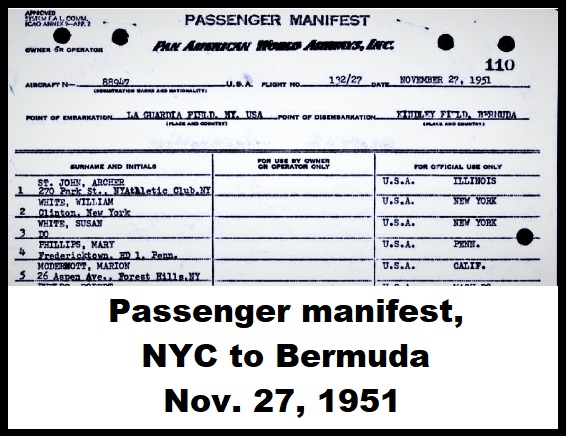

Gertrude stayed in Virginia, at Bushfield, while son Michael attended the University of Virginia. Archer, at least initially, split his time between that home and New York. Even while he was in the throes of his affair with Marion, he was still involved with life on his Mount Holly farm. One newspaper article from October 1951 noted that he was the top bidder for a prized Hereford heifer. Yet, just a month later, he and Marion took a flight together to Bermuda.

Passenger manifest, NYC to Bermuda

Nov. 27, 1951

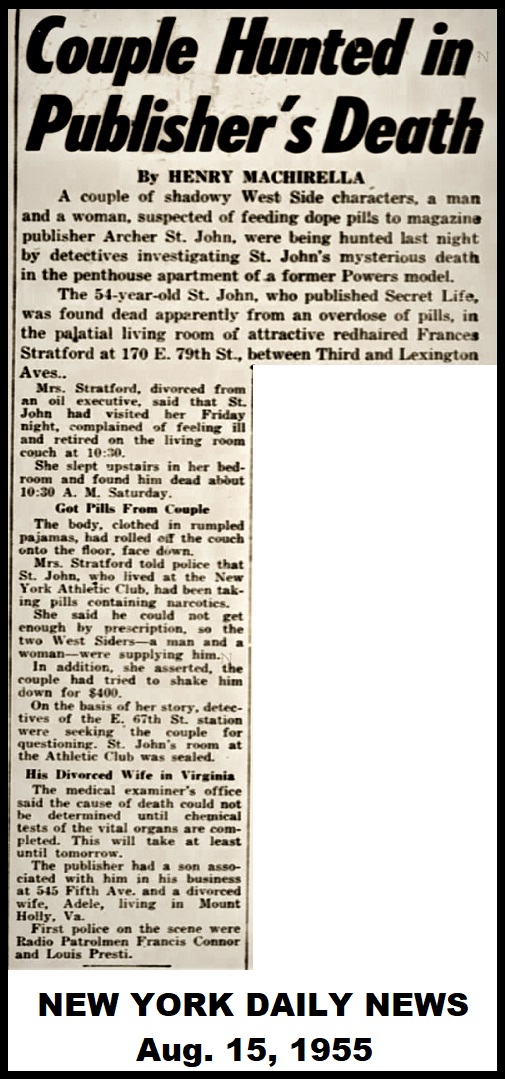

Marion remained working for St. John Publishing into 1954 and possibly even later. Owner’s statements made on Oct. 1, 1954, corroborate that information. Whether or not her romance with Archer continued as well is understandably unknown. In any case, it all came to a quick end with the death of Archer St. John on August 13, 1955. The sordid circumstances of Archer’s death was welcome fodder for the tabloids

“A couple of shadowy West Side characters, a man and a woman, suspected of feeding dope pills to magazine publisher Archer St. John, were being hunted last night by detectives investigating St. John’s mysterious death in the penthouse apartment of a former Powers model.”

“The 54-year-old St. John, who published Secret Life, was found dead apparently from an overdose of pills, in the palatial living room of attractive redhaired Frances Stratford at 170 E. 79th St., between Third and Lexington Aves.” [Machirella, Henry, “Couple Hunted In Publisher’s Death,” NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, August 15, 1955.]

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Aug. 15, 1955

A subsequent autopsy showed that he indeed died of an overdose of amphetamines. Whether it was accidental or intentional was never determined. Behind the scandalous headlines, though, was a personal tragedy. Despite their estrangement, Gertrude had lost a husband and Michael a father.

Some sources claim that the Monday after Archer’s death, Gertrude angrily stormed into the offices of St. John Publishing and fired most of its staff. Michael St. John, only 25 years old at the time, was thrust into the role of publisher and he would head the company through the rest of its existence, for better and for worse.

Gertrude returned to Virginia and in April 1957, she put the Bushfield estate up for sale.

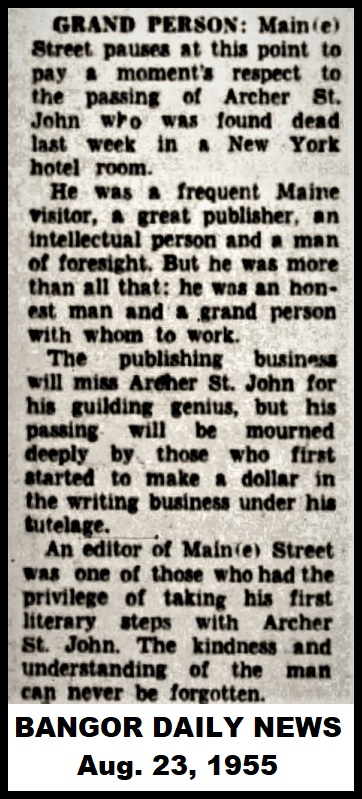

BANGOR DAILY NEWS

Aug. 23, 1955

Not everyone had such a bitter reaction to Archer’s death. A week after it was reported, a column run in a Maine newspaper made reference to Archer’s demise and recalled the publisher fondly.

“Main(e) Street pauses at this point to pay a moment’s respect to the passing of Archer St. John who was found dead last week in a New York hotel room.”

“He was a frequent Maine visitor, a great publisher, an intellectual person and a man of foresight. But he was more than all that: he was an honest man and a grand person with whom to work.”

“The publishing business will miss Archer St. John for his guilding [sic] genius, but his passing will be mourned deeply by those who first started to make a dollar in the writing business under his tutelage.”

“An editor of Main(e) Street was one of those who had the privilege of taking his first literary steps with Archer St. John. The kindness and understanding of the man can never be forgotten.” [“On the Main(e) Street,” BANGOR DAILY NEWS, Aug. 23, 1955.]

This unsigned tribute was actually the work of Dana Dutch. Dutch was a summer resident of Castine, Maine and a part-time editor of the local newspaper. His touching recollection of Archer was reflective of many who knew him. A talented, generous man, beset with flaws.

FORT LAUDERDALE NEWS

Sept. 23, 1966

But what about Marion McDermott? What happened to her in the wake of Archer’s death? The mystery of Marion McDermott begins when her career at St. John Publishing ends.

If the recollection of Nadine King were accurate and Marion contributed to the creation of NUGGET magazine in 1955, she was there right up until Archer died. At this point, Marion McDermott seems to disappear, only to reappear under a different name in February 1956. At this time, Social Security records indicate that she changed her name to Marion Cameron.

Most times when a woman changed her name, it was as a result of her marriage and she had taken the last name of her new husband. If Marion had married, though, no record of it has yet been found. To compound the mystery, she also is named as the mother of a son named Christopher Cameron, born April 24, 1953.

This surprising fact raises more questions: If she is indeed the mother of this boy, then she gave birth when she was working at St. John Publishing. If so, who was the father? Did she marry him? And whatever happened to him?

Not one former co-worker of Marion’s ever mentioned that she had married, nor given birth to a son. It would seem it would have been mentioned by someone, particularly in light of her affair with Archer.

About the same time she began using the last name of Cameron, Marion relocated to Florida in 1956, where she found work at WTVJ, the largest television station in Miami. The rest of her family, her parents and her brother William, all moved to Florida as well. In 1966, Marion was named as the on-air promotion coordinator at the station. She remained in that position until her retirement in July 1978.

Still, the only time a husband is mentioned at all came in an article regarding a flock of guinea fowl found a home on her street and it resulted in a feature article in the local newspaper.

“The neighborhood, which lies south of Granada Golf Course, has been home to the father of the [birds] for two years, said Chris Cameron., who lives next door to [756 Malaga Ave.]. Cameron and other neighbors have been feeding the bird who wheat crumbs since he showed up.”

“This spring, the bird started wailing again. Within weeks, another female came.”

“‘And on May 27,’ Cameron’s wife Marion said, ‘the whole family came around the corner–they looked like 23 fur balls rolling in the grass.'” [Kollars, Deb, MIAMI HERALD, July 11, 1985.]

That was it. So, was Christopher also the name of Marion’s husband? Or did the reporter mistakenly identify Marion’s son as her husband?

To make it even more confounding, Social Security records indicate that Christopher Cameron died in October 1986 at 33 years of age. And no obituary has yet been found.

These mysteries aside, Marion lived a full life after her retirement. When she died on May 14, 1999, her obituary summed up her final years.

“Her many charitable works included 10 years as a Hospice volunteer and the editor of the Hospice newsletter. A reader for the blind, [she] worked with the Missionary of Charity. A weaver of stories, a world traveler, she took great joy in being a practitioner as of Tai-Chi as taught by Stephen Chin.” [“Obituary: Cameron, Marion, MIAMI HERALD, May 17, 1999.]

While her obituary listed her next of kin, missing were any mention of a husband, alive or dead, or her son Christopher.

EPILOGUE:

The story of Marion McDermott is yet to be fully told. Not only is there the curious lack of information regarding her name change, her presumed marriage to a man named Cameron or details about her son Christopher, but her legacy as a comic book editor is framed by her personal relationship with Archer St. John.

Despite his intellect, his noteworthy accomplishments as a journalist, and the testaments to his kindness and generosity, Archer St. John had another side. In many ways he was the stereotypical “Mad man” portrayed in books and film. The respectable, gray flannel-suited Manhattan businessman who was also a heavy drinker and, in the parlance of the era, a womanizer. He died over a drug overdose, yet according to Irwin Stein, “Archer St. John was a very uptight, very moral guy,” but Stein added, “it was a convenient morality.” [Benson, 12.]

Marion’s career in the comic book industry died with Archer. She changed her name, moved to another state and followed an entirely different career path. Such drastic decisions are not usually made casually or without reason. The mystery of Marion McDermott will only be solved if her decisions could be explained. And those explanations may have died with her.