©2020 Ken Quattro

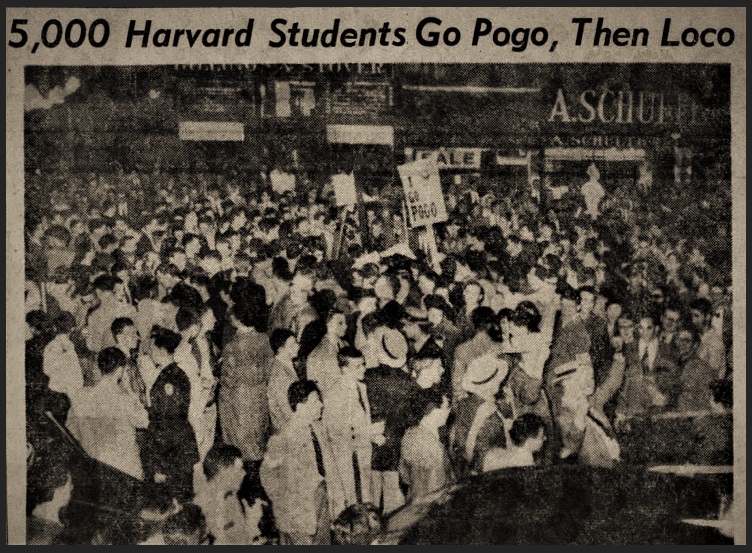

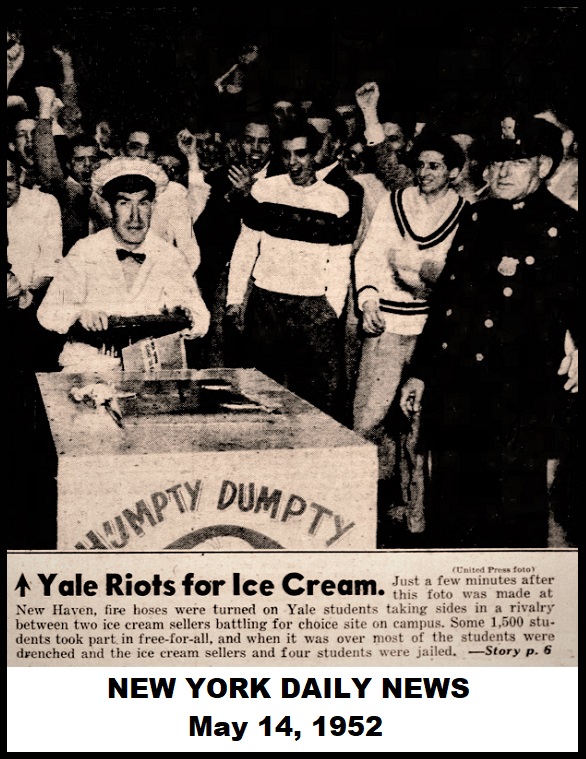

“For three days last week, Yale students watched with interest as two ice-cream venders [sic], a Good Humor man and a Humpty Dumpty man, jockeyed for position outside the university post office, a choice sales spot. Finally the argument became so heated that police told the venders [sic] to move along. A handful of undergraduates rushed into the street, shouting encouragement to either Good Humor or Humpty Dumpty. Other students jeered police from their windows and tossed paper bags filled with water down into the street.”

Just about anyone could relate to the scene. Mild spring days on a venerable college campus, a backdrop of ivy-covered buildings, budding trees, a quaint New England setting. And young men, full of life and pent-up energy, letting off some steam at the end of a school year.

“Exuberant with spring fever and the last day of classes before examinations, students poured from their rooms. Firecrackers exploded. Within minutes, 1,200 undergraduates joined in the noisy demonstration. Traffic was stopped. Fist fights erupted between Good Humor partisans and their Humpty Dumpty adversaries.”

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, May 14, 1952

“As the milling students organized a march to the Hotel Taft a block away, New Haven [CT] Police Chief Howard Young rushed 80 police to the scene, ‘This is a mob and we’re treating them as such,’ he said angrily. Police turned their nightsticks and three fire hoses on the students, trying to drive them back inside campus gates. But collegians swarmed to the hydrants and turned the water off. It was turned on again.”

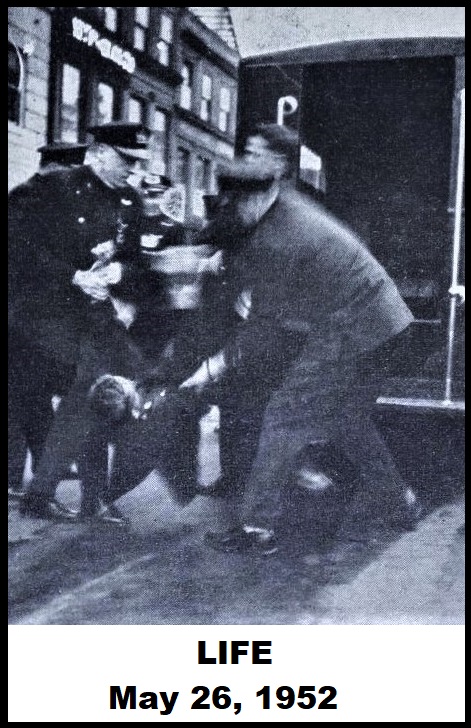

NEWSWEEK, May 26, 1952

“Two hours later, the free-for-all subsided. Four undergraduates were arrested and scores were treated for minor injuries.” [“Riots: Busting Out All Over,” NEWSWEEK, May 26, 1952.]

The story spread and was carried in newspapers throughout the country, some containing more detail.

“A motorist tried to drive through the fist-swinging students, but they turned on him, broke windows of his automobile and forced him to flee on foot.”

“[The students] attempted to attack a bus driver, but he opened a window and squirted chemical from a fire extinguisher upon them before driving slowly off with his fares.” [“Griswold Apologizes for Riot in Ice Cream’s Cause at Yale,” BERKSHIRE EAGLE, May 14, 1952.]

For many older folks, the events at Yale were part of a disturbing trend. Long accustomed to sophomoric pranks and peer-pressured fads such as goldfish swallowing and phone booth stuffing, seasoned observers saw a move from harmless fun to confrontational behavior that sometimes resulted in violence.

“More than 1,000 prankish Columbia University students staged a panty raid on Barnard College early today and the girls got blamed for egging them on.”

“The raid was another in a series of springtime revolts on America’s college campuses.”

“Male college raiders have sought out co-ed lingerie previously at the Universities of Florida, Nebraska, Iowa, Purdue, Denver, Otterbein College in Ohio and Yale University.”

“Columbia began its own investigation of the raid, which lasted more than two hours. One policeman was hurt and one male student received a disorderly conduct summons.”

“In Miami, 3,000 male students raided girls’ dormitories on the university’s main campus s the co-eds waved and beckoned them on. Fire hoses were used by police to quell the boisterous young men.”

“Windows were broken and one student was cut and bruised in more than an hour of rioting.” [“Panty Raiders Rock Ol’ Barnard’s Serenity, But Look Who Is Blamed—Girls, No Less!” CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, May 17, 1952.]

The Yale “ice cream riot” was a great embarrassment for the hallowed university. Like most Elis, Yale President, A. Whitney Griswold was chagrined.

“‘On behalf of the university, I wish to express my sincere apologies to the community,’ Griswold said.” [“Griswold Apologizes,” op. cit.]

Meanwhile, Yale’s arch rival was delighting in the unwanted attention being given its Ivy League nemesis.

“Up in Cambridge, Mass., Harvard student leaders said smugly that nothing like the riot at Yale could happen there. ‘Cambridge police are among the nicest in New England,’ explained David Rattner, senior editor of The [Harvard] Crimson. ‘No Harvard man would ever eat ice cream anyway.'” [“Riots: Busting Out,” op. cit.]

The Harvard men would soon have reason to regret those words.

__________________________________________

Walt Kelly was having a very good year.

In March, THE GLOB, a children’s book written by John O’Reilly and illustrated by Kelly, was released to mostly good reviews. COLLIER’S magazine ran a two-page pictorial on “Pogo’s Papa” in that same month. On April 22, it was announced that Kelly had received the Billy DeBeck Award from the National Cartoonist’s Society as “Cartoonist of the Year.” Then a few days later, Pogo began his run for the White House.

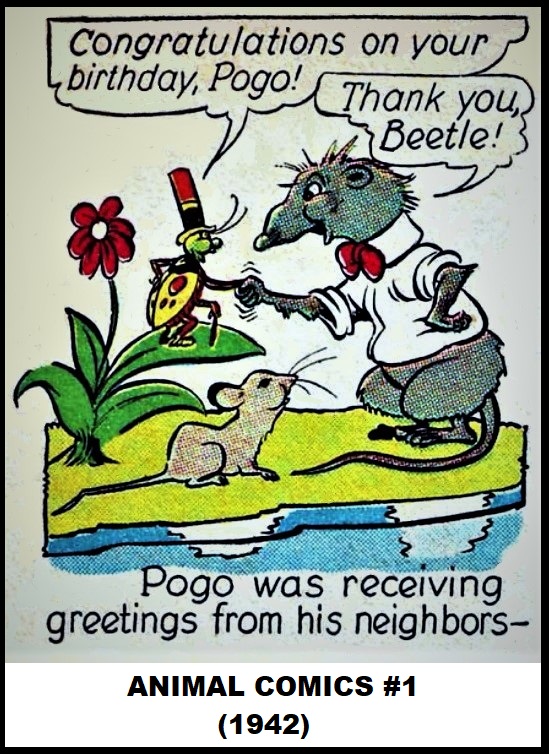

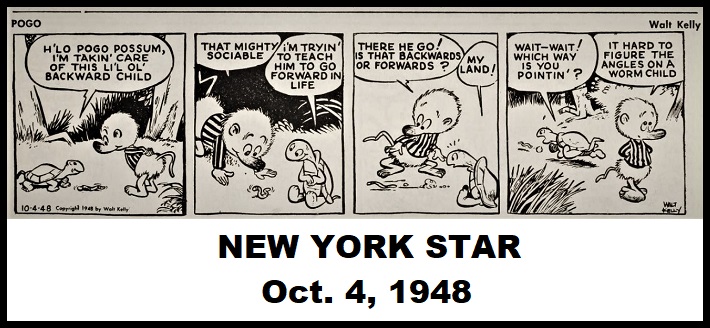

From their humble beginnings in the pages of ANIMAL COMICS #1 back in 1942, Pogo and the other denizens of Okefenokee Swamp had made the prestigious leap to the newspaper page. First appearing in the NEW YORK STAR in October1948, where Kelly had been employed as a political cartoonist. The strip was taken on by the Post-Hall Syndicate when the STAR folded in February 1949, and by 1952, it was seen in over 250 newspapers.

ANIMAL COMICS #1, (1942)

panel introducing Pogo

From its inception as a newspaper comic strip, Pogo had risen into the rarefied strata inhabited by Krazy Kat, Barnaby, Will Eisner’s The Spirit and few others, as strips appealing to children and adults alike. Indeed, Pogo enjoyed a readership among a specific demographic that was unique among its peers.

“…from the fan mail Kelly has received since ‘Pogo’ began his career some five years ago, it is obvious is for adults. Kelly has stacks of mail from college students and college professors; very little from youngsters.” [Williams, Doris, “Walt Kelly’s ‘Pogo’ Ribs Stupidities of Mankind,” EDITOR & PUBLISHER, Dec. 11, 1948.]

NEW YORK STAR, Oct. 4, 1948

First Pogo comic strip

In the ensuing years, Pogo’s popularity grew. It should not be overlooked that part of the reason for Pogo’s broad spectrum of acceptance came from the fact that Kelly’s brilliant satire crossed ideological boundaries. Sen. Joseph P. McCarthy (as Simple J. Malarkey) was as likely a target as were Communists (represented by the Cowbirds). Rock-ribbed conservatives as well as bleeding-heart liberals could get a laugh from Kelly’s creation. Although sharp, his needling rarely broke the skin.

By 1952, Pogo boasted a worldwide readership of over 37 million; many of whom were college students.

Pogo’s collegiate following was understandable. The tiny marsupial and his fellow swamp critters offered searing observations on current political and societal issues under the guise of innocent naivete. Kelly’s humor, both canny and clever and delivered in the strip’s patented patois, provided an ongoing anti-establishment commentary without the meanness of partisan acrimony. The college kids “got it” and adopted Pogo as their philosophical mascot.

It was perhaps only logical then that Pogo would emerge as the preferred Presidential pick of many collegians in the upcoming election in November 1952.

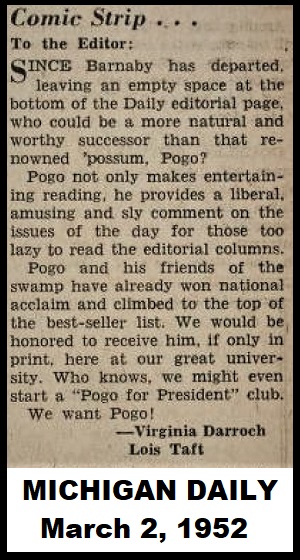

MICHIGAN DAILY, March 2, 1952

Even before the snows of winter had melted in early 1952, even before the major parties had held their first primaries, rumblings of “Pogo for President” were being heard on campuses. One letter to the editor of the MICHIGAN DAILY mentioned a possible candidacy along with a request for the strip’s publication in the paper.

“Pogo and his friends of the swamp have already won national acclaim and climbed to the top of the best-seller list. We would be honored to receive him, if only in print, here at our great university. Who knows, we might even start a ‘Pogo for President’ club.”

“We want Pogo!” [Virginia Darroch and Lois Taft, “Comic Strip…” Letter to the Editor, MICHIGAN DAILY, March 2, 1952.]

Kelly and the Post-Hall Syndicate were well aware of this grassroots groundswell and decided to take advantage of it.

Under the “Book Notes” subheading in the April 7 NEWSWEEK, it was noted that “‘I Go Pogo,’ a new $1 collection of Walt Kelly comic strips, will appear in September. It describes a campaign to put the possum in the White House. This sequence, starting soon in newspapers, was promoted by college Pogo clubs.” [“The Periscope,” NEWSWEEK, April 7, 1952.]

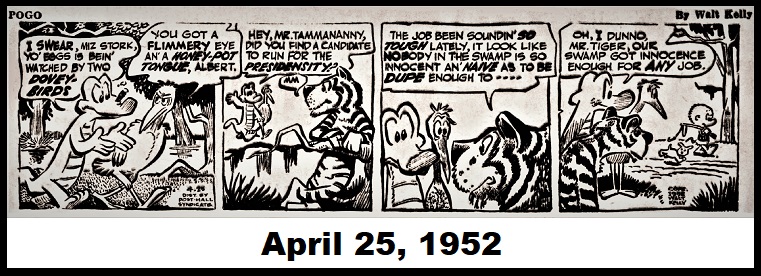

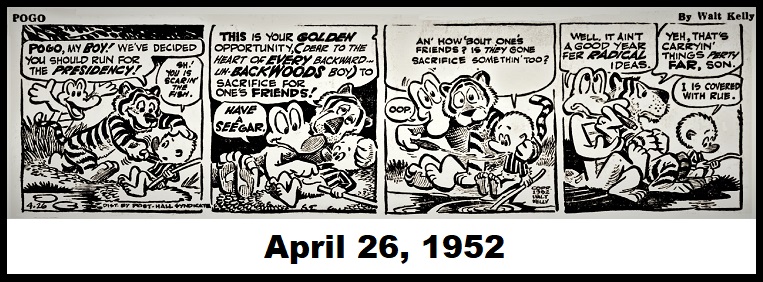

Sure enough, the first indication that Pogo was running came on April 25, 1952. In the ensuing weeks, the continuity followed the drafting of Pogo as a candidate by his pal Albert and Mr. Tamannanny, a politically-connected tiger who had come to the swamp in search of “The Big Boy,” an unnamed and elusive figure that was the preferred choice of Tamananny’s bosses.

April 25, 1952

April 26, 1952

Knowledgeable readers of the era would have understood Kelly’s winking reference of “The Big Boy” as representing Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the still-serving military hero of WWII who wasn’t yet able to officially throw his hat into the Presidential ring until he retired from the Army. Mr. Tamananny, apparently clueless to the identity of “The Big Boy,” recruits Pogo in his stead and the opossum’s political career takes off from there.

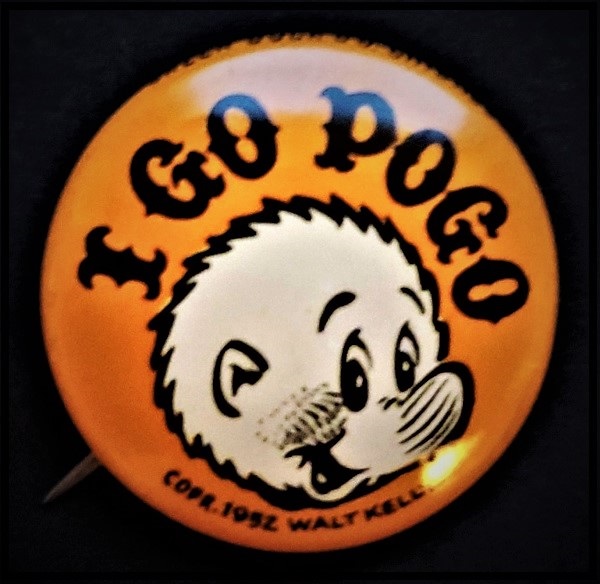

“I Go Pogo” button, 1952

“Pogo for President” clubs had already begun springing up on college campuses by the time this sequence appeared. The enterprising Kelly had ordered some 50,000 “I Go Pogo” celluloid pins, which were quickly gobbled up by students desperate to display their support.

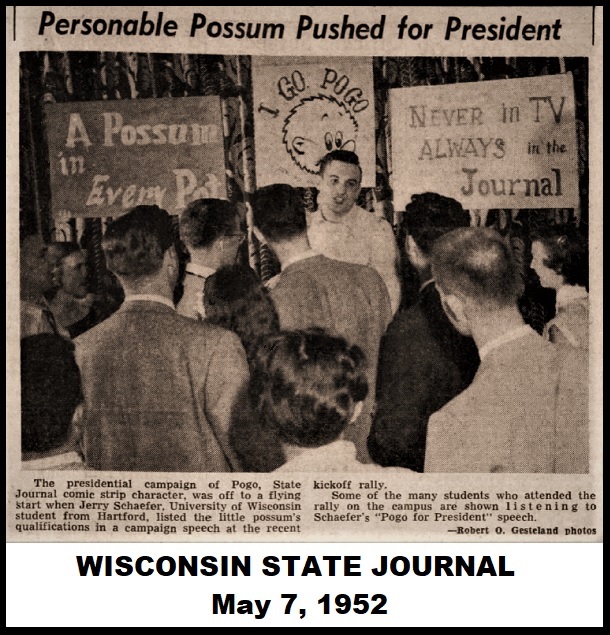

“Fact is, a University of Wisconsin co-ed is hardly dressed at all these days unless she’s wearing a [n] ‘I Go Pogo’ button.” [“Students All Go for Pogo as Drive, Right on Button, Sweeps UW Campus,” WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL, May 7, 1952.]

WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL, May 7, 1952

Concurrent with the “Pogo for President” continuity, Kelly planned a nationwide tour of college campuses to tout the candidacy and to exploit the publicity it drew. He also contacted schools personally, advocating for the campaign and offering buttons, encouragement and organizing suggestions to spread the word.

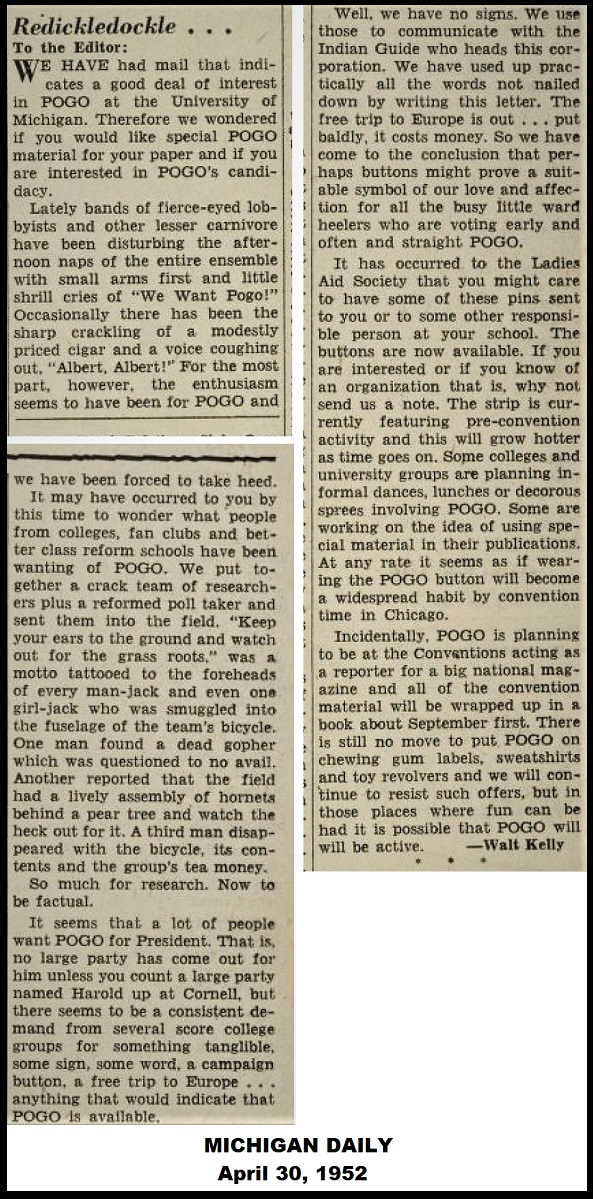

MICHIGAN DAILY, April 30, 1952

“It seems that a lot of people want POGO for President. That is, no large party has come out for him unless you count a large party named Harold up at Cornell, but there seems to be a consistent demand from several score college groups for something tangible, some sign, some word, a campaign button, a free trip to Europe…something that would indicate that POGO is available.”

“Well, we have no signs. We use those to communicate with the Indian Guide who heads this corporation. We have use up practically all the words not nailed down by writing this letter. The free trip to Europe is out…put baldly, it costs money. So we have come to the conclusion that perhaps buttons might prove a suitable symbol of our love and affection for the busy little ward heelers who are voting early and often and straight POGO.” [Kelly, Walt, “Redickledockle…” MICHIGAN DAILY, April 30, 1952.]

Walt Kelly and wife Stephanie

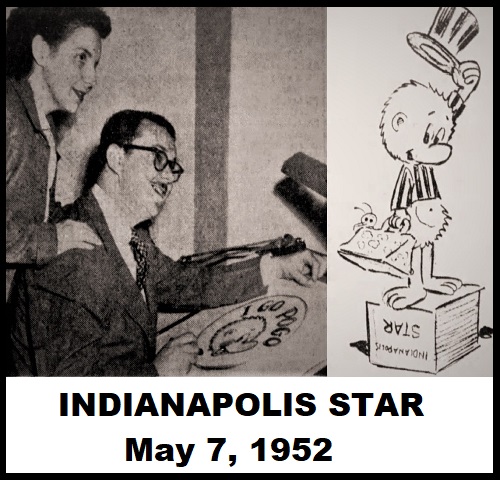

INDIANAPOLIS STAR, May 7, 1952

Not to be left out, Ivy League schools wanted in on the fun as well. On May 7, Harvard University received one of Kelly’s letters accompanied by a box of the coveted buttons.

“A carton containing 3000 of these buttons was left on the CRIMSON’s door-step last night, and in the cause of equal representation for all political movements, these buttons will be available to all students at the CRIMSON building while they last. . . “ [“I Go Pogo,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 8, 1952.

News of the buttons arrival spread quickly and the demand for them seemed to catch everyone off guard.

“Hundreds of students, faculty members and men in the street swarmed to the CRIMSON building yesterday morning and emptied it of over 3,000 I GO POGO buttons in little over an hour and a half. Long after the Pogo for President buttons were gone, people kept filing into the building with mute pleas in their eyes for more. There will be several thousand more early next week.”

“Jay R. Nussbaum ’53, who quickly began plans for forming a University Pogo club, admitted surprise last night at the reception the little ‘Possum had received. ‘It’s beginning to look serious,’ he muttered when contacted last night.” [“Pogo Starts Ruckus,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 9, 1952.]

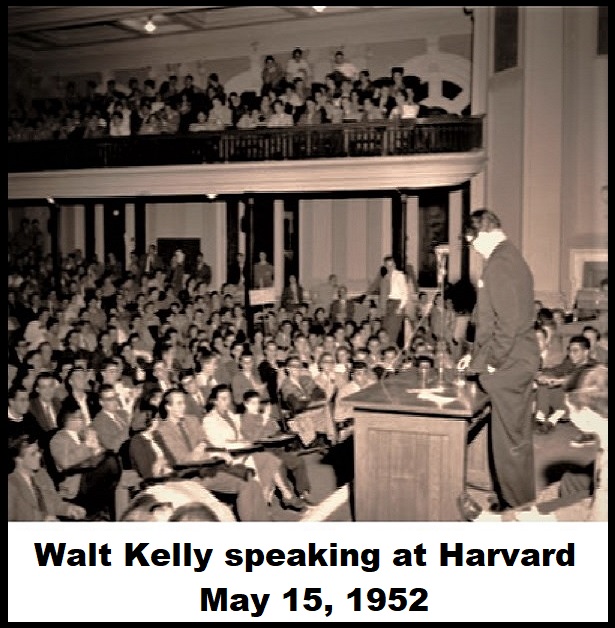

Kelly must have been aware of this outpouring of support at Harvard and the attention it would bring. Even though he had already started upon his “Pogo for President” tour, he scheduled a talk at the prestigious university.

“Walt Kelly, creator and curator of Pogo, the presidential ‘possum, will speak at the New Lecture Hall at 7:30 p.m. tomorrow, his New York office announced yesterday. Kelly plans to Begin his national stumping tour in Cambridge, and will deliver a chalk talk, free of charge, ‘to everyone who can take it.'”

“A mess demonstration will begin for Okeefenokee’s favorite son in Harvard Square at 7:00. Signs and buttons will be distributed to all marchers. Anyone who wishes to play in the band should get in touch with the CRIMSON before then.”

“Meanwhile, a spontaneous demonstration for Pogo broke out at the second Yard concert last night, when the Lampoon stunt men began their act. Cries of “We Want Pogo” went up, followed by a steady underchant of ‘I–Go–Po–Go.'” [“Walt Kelly, Pogo’s Pa, To Deliver Chalk Talk On ‘Possum Thursday,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 14, 1952.]

All seemed to be in order for Kelly’s talk and a planned rally in honor of his visit.

“[Cambridge] Police Chief Patrick J. Ready gave his go ahead yesterday–to the Pogo rally scheduled before Walt Kelly’s talk tonight. Kelly will speak in the New Lecture Hall at 7:30 p.m.”

“Pogo’s penman [Kelly] will arrive from New York on the evening train, and meet the demonstrators in the Square at 7, from where he will lead the parade to the New Lecture Hall.” [“Walt Kelly, Pogo’s Creator, Due In Town for Chalk Talk Tonight,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 15, 1952.]

Walt Kelly speaking at Harvard

May 15, 1952

The CRIMSON staff dutifully covered Kelly’s talk, without indication of any problems surrounding the event.

“More than 1000 students jammed New Lecture Hall last night to attend the most popular course of the year-a one night stand by Pogo’s papa, Walt Kelly.”

“The rotund and genial creator of the comic strip possum had a little difficulty with traffic conditions in the Square and arrived a few minutes late for his scheduled lecture. Kelly, in fact, spent the first part of his informal talk explaining to students his impression of ‘the way a person in a uniform must feel when surrounded by so many people without uniforms.'”

“Kelly, who was given a three-minute ovation at the start of his speech, had obviously been well-instructed before hand in local jokes. He mentioned ‘little disturbances in a place down the line that had something to do with ice cream’ and added that he had heard of some trouble in Cambridge when a fellow who couldn’t sleep at night went looking for his socks.”

“His talk was interrupted at several points by pogo stick races down the aisles.” [“Over 1000 Fill New Lecture Hall For Cartoonist Kelly’s Pogo-Talk,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 16, 1952.]

This account of Kelly’s speech focused on his talk itself; a trifling bit of entertainment sprinkled with the expected witticisms and an off-hand reference to the recent Yale “disturbances” that “had something to do with ice cream.” Other than the casual mention that Kelly was slightly detained due to “a little difficulty with traffic conditions in the Square,” there were no indications that anything out of the ordinary had occurred. Whether by choice or assignment, this CRIMSON reporter noted nothing of what happened outside the lecture hall. It fell to other reporters for the paper to supply that perspective.

“The long arm of the law came to Harvard Square last night swinging its billy club, swimming it hard and to the head and not pulling its punch. It was police-state law, the enraged and petty law of men who know something is wrong and don’t know what to do about it, the frustrated law of men who are laughed at and can only reply with a quick crack at your skull.” [“The Riot Squad,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 16, 1952.]

Though this incensed paragraph gave little detail, it was apparent that the scene outside the New Lecture Hall where Kelly was giving his talk was anything but peaceful. The local Boston newspapers provided a fuller account of the circumstances in Harvard Square.

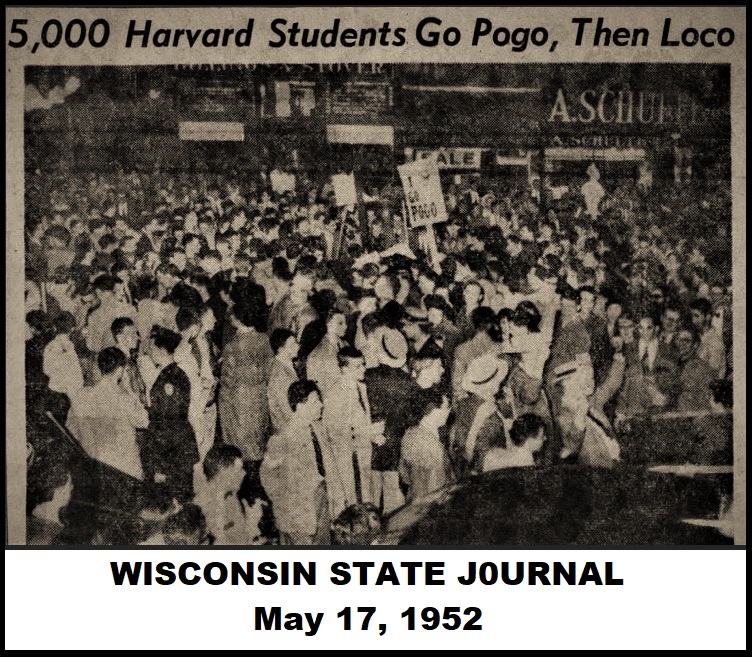

WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL, May 17, 1952

“Trouble started in Harvard sq. [sic] last evening after a mock Presidential campaign involving ‘Pappy Yokum,’ a hillbilly character in Al Capp’s ‘Li’l Abner’ comic strip and ‘Pogo,’ another comic strip character.” [“Harvard Pair Get Day in Jail,” BOSTON EVENING GLOBE, May 16, 1952.]

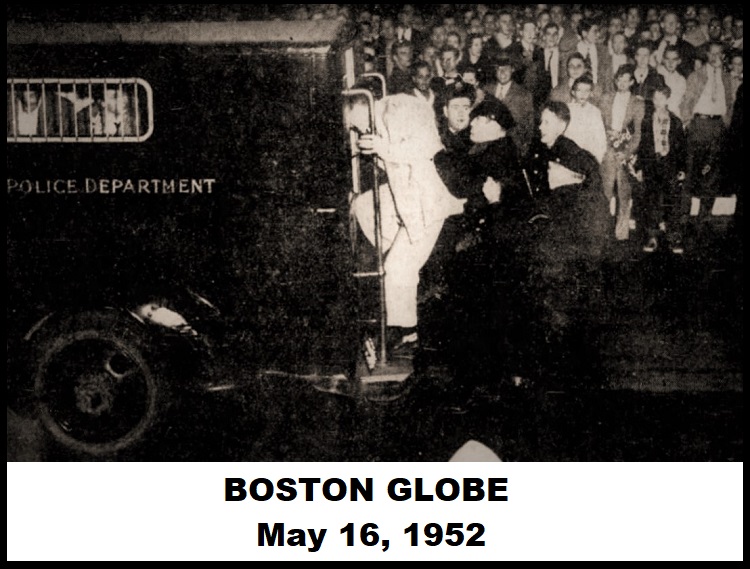

BOSTON GLOBE, May 16, 1952

“The demonstration got under way in orderly fashion around 7 p.m. when 500 students poured into the square from nearby dorms, but within the hour it got out of hand and police stepped in to break up the throng which had grown to around 2000 Cantabrigians.”

“With Harvard sq. [sic] traffic blocked and snarled along all streets surrounding the area, Sgt. Anthony Rubbicco, in charge of a detail of 20 Cambridge police officers, ordered the students to disperse after it was noted that several were engaged in pulling down poles from the trolley cars.”

“Apprehension of one of the students involved in ‘Operation Trolley Car’ changed the pep rally into a near riot.” [“28 Arrested in Melee at Harvard,” BOSTON GLOBE, May 16, 1952.]

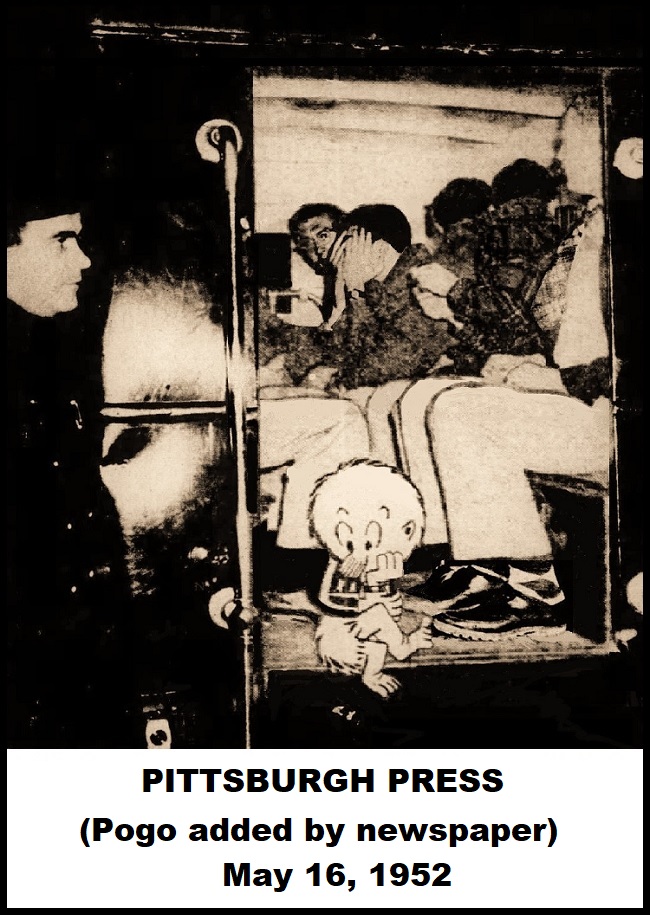

PITTSBURGH PRESS

(Pogo added by newspaper)

May 16, 1952

As is often the case, accounts of what happened varied wildly. The official police version, reported in the city’s newspapers and around the nation, differed from the students. The uncredited author of this CRIMSON report gave a well-written, if biased, description.

“By and large, local police have been a tolerant lot, not unfriendly to the demonstrations that periodically crop up in the Square. But last night the police went out for a fight and when it didn’t turn up, they made one. They had given their permission for the rally. Yet they reacted to the crowd in the Square with the indignant surprise of a man who has found a herd of goats in his vegetables garden. The crowd was not particularly large nor unruly by local crowd standards. Yet the police waded into it as if it were hell bent for the vaults of the Harvard Trust Company. They insulted women and bashed undergraduates and ripped out camera films and told proctors to ‘go back where you come from.’ It was a good chance to throw around a little weight. One cop summed it up pretty well: ‘We knew they were cutting up a little, so we came down to break it.'” [“The Riot Squad,” op. cit.]

LIFE, May 17, 1952

Another student wrote a less-flowery account in the same issue of the CRIMSON that filled in some detail.

“According to signed statements delivered to the CRIMSONS, many people were arrested ‘for no reason at all’ and dragged by force to waiting police cruisers and paddy wagons.”

“‘Clubs were used freely,’ eye-witnesses said; many prisoners were cut and bleeding.”

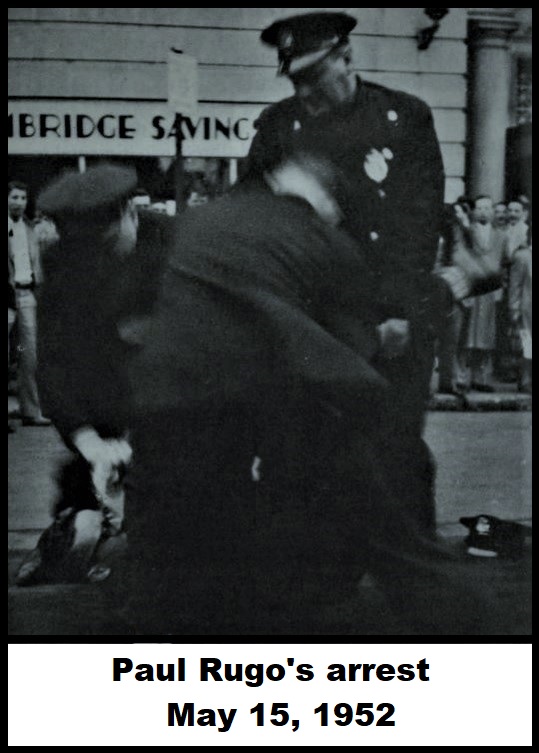

“One report told of how Paul Rugo ’55, who was walking along with his date, was apprehended by a patrolman. He said ‘You’re under arrest.'”

“‘What for?'” Rugo asked.”

“The policeman replied, ‘Never mind, come with me.'”

“The account by Guy Ciannaver ’55 stated that ‘Rugo struggled…and the cop was joined by four others. During the course of the fight he was struck by clubs on the left cheek and skin.'”

“Another student, Theodore Rose ’54, elaborated on the story. ‘The cops piled on him,” he said,’ ‘two holding and three hitting. They used clubs freely, and he had a gash on the side of his face. The coat of his ROTC uniform was open and the buttons ripped off.'”

“A CRIMSON photographer, Norman Weil, Jr. ’54, claimed that the officer who arrested him said: ‘Getting arrested will teach you Harvard bastards a lesson.'”

“‘One student merely tried to cross the street,’ Ira Levy ’54 said. ‘A cop came up to him and said ‘get going.'” He said ‘I am, I am,’ and tried to get away. The policeman started to push him and then dragged him toward the Waldorf Cafeteria and the cruisers.'”

“Another CRIMSON editor, David L. Halberstam ’55, claimed that he had been kneed in the groin by one policeman after that officer had failed to catch a photographer he had been chasing.” [“Students Claim Mishandling In Police Methods at Melee,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 16, 1952.]

[note: Halberstam would eventually become the Managing Editor of the CRIMSON, but went onto even greater fame as a noted journalist and author.]

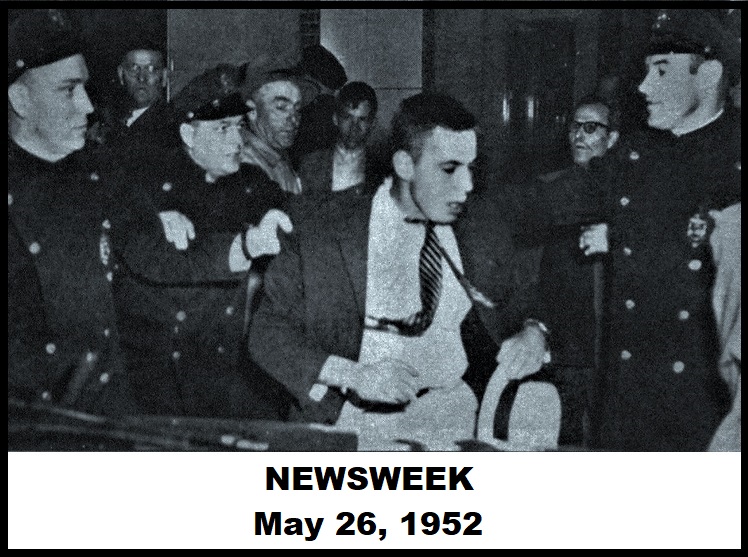

NEWSWEEK, May 26, 1952

Similar complaints of police brutality appeared in the mainstream newspapers as well, but these publications leaned heavily upon the official accounts.

“Responding slowly to orders to disperse, the students cast threats at police and found themselves tossed into one of two ambulances shortly after the word left their lips.”

“Police ordered all prowl cars in the city to the scene to augment the detail assigned to the square. Alvan T. Randall, chief of the Harvard Yard police, put in an appearance in civies. He was the sole member of the force seen in the square.”

“Their pep demonstration stamped out by police, the students then marched to the new lecture hall on Kirkland st. [sic], where they were addressed by the comic strip author, Walt Kelly, in whose honor the rally had been planned.”

“Kelly was cheered to the echo every time he started to talk and his words were drowned out in the tumult. From snatches of his talk that penetrated the noise, it appeared that Kelly was flattered that his comic strip could generate such enthusiasm but he indicated he also was sympathetic to police who had to deal with such enthusiasm.” [“28 Arrested,” op. cit.]

And students were not the only ones claiming injuries. The same article reported that, “It was a rough ‘campaign’ for at least three Cambridge patrolmen. One was treated for a bite at Cambridge City Hospital, a second was hit on the head with a beer can and a third suffered contusions and abrasions of the hand in a tussle.” [“28 Arrested,” op. cit.]

BOSTON GLOBE, May 16, 1952

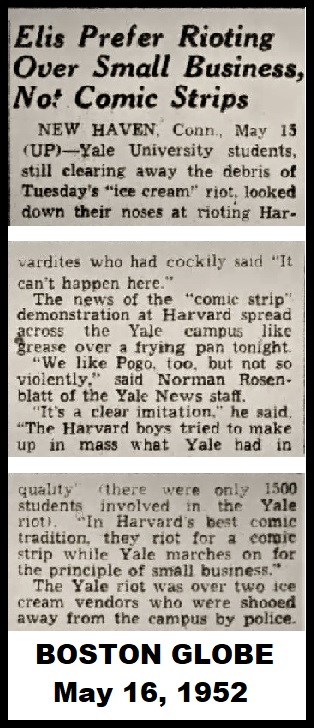

Needless to say, news of the Harvard troubles were met with glee in New Haven, Connecticut.

“Yale University students, still clearing away the debris of Tuesday’s ‘ice cream’ riot, looked down their noses at rioting Harvardites who had cockily said, ‘It can’t happen here.'”

“We like Pogo, too, but not so violently,’ said Norman Rosenblatt of the Yale News staff.”

“‘In Harvard’s best comic tradition, they riot for a comic strip while Yale marches on for the principle of small business.'” [“Elis Prefer Rioting Over Small Business, Not Comic Strips,” BOSTON GLOBE, May 16, 1952.]

Charges and counter-charges were made by both sides of the Harvard dust-up in the coming days. Twenty-eight students, including at least five staff members of the HARVARD CRIMSON, were arrested. The school paper carried articles regarding the melee for weeks, each supplying a new bit of information from eye-witnesses, ongoing coverage of court appearances and even nuanced discussion of whether the incident should be termed a “rally” or rose to the level of a “riot.” The terminology mattered. If Harvard’s Administrative Board considered it a “riot,” those students who were already facing criminal charges could face discipline and perhaps even expulsion from the university.

“This assumes that those present were there expecting a riot, which was not the case last Thursday. The occasion then was an authorized demonstration in honor of a cartoonist, and the majority of the demonstrators had no interest in pulling trolley wires or over-turning automobiles. The rally became something of a riot only when the police arrived in force, and it is difficult to expect everyone present to scamper off quickly before the object of their interest had arrived. In this particular case, there was obviously no riot in the usual sense of that word, and the Mere Presence rule should not apply.” [“Riot Policy: II,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 21, 1952.]

Of the 28 arrested, 26 pleaded “not guilty” at their May 16 arraignment, while two others were convicted of disturbing the peace, sentenced to one night in jail. The duo immediately filed an appeal. Paul Rugo, the student whose photographed arrest was published in newspapers and magazines all around the country, was the only one charged with assault and battery.

Paul Rugo arrest

May 15, 1952

“The complainant against Rugo is patrolman William Story, one of the four officers who helped put Rugo in the patrol wagon when he was arrested during the riot. Story said the student, who was with a date at the time, violently resisted arrest.” [“Rugo Given Separate Hearing for Battery, Assault Charge Friday,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 21, 1952.]

Walt Kelly personally offered to pay the $25 bail for each student charged.

In the days leading up to the trial of the students, a protest was held and the CRIMSON gathered more than 50 eyewitness accounts supporting the students version of events. They also reported that the Law School’s Voluntary Defenders, a group usually restricted to doing pro bono work for indigent persons, offered legal assistance to any student needing it.

In a surprising move, the mayor of Cambridge, Joseph A. DeGuglielmo, was asked and agreed to be the attorney representing the five CRIMSON staff members. It is not hard to imagine that the mayor’s counsel was motivated by political expediency given the influence of Harvard’s moneyed families.

The trial of the student defendants got national attention, with the plight of the five CRIMSON staff members particularly in the spotlight.

“A member of the American Society of Newspaper Editors [ASNE] has asked the Cambridge chief of police to explain reports that police interfered with The Harvard Crimson’s coverage of the May 15 clash between officers and students.”

“[James S.] Pope, executive editor of the Courier-Journal and Times, Louisville, Ky., said ‘The Crimson feels that the newsmen have been discriminated against in that they were not permitted to cover the event properly by your police. Also, there is clear evidence (we have a picture of the remains of the films) that one of your officers destroyed film belonging to a Crimson photographer.” [“U.S. Editors Group Asks Why Newsmen of Harvard Arrested,” BOSTON GLOBE, May 26, 1952.]

Pope was the chairman of the ASNE’s Freedom of Information Committee and he wasn’t about to let the issue go.

“‘So far as we know,’ [Pope] continued, ‘there is no law in the State of Massachusetts against snapping a camera in a public place. If not, it would seem to us that the photographer and the Crimson have a legitimate suit for damages against anyone who willfully destroyed their property and damaged the publication of their newspaper without legal warrant.'”

“In Cambridge, Chief Ready’s reaction was: ‘I would like to sit down with Mr. James Pope and talk this matter over. It is very evident he has no idea what we have to put up with in Cambridge.'” [“ASNE Aide Intervenes in Pogo Riot,” CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR, May 26, 1952.]

Ultimately, it was all for naught.

“A hurried deal with the Cambridge police brought to a quick close Tuesday what had promised to be a long but interesting trial of students arrested for disturbing the peace at the May 15 Pogo rally in the Square.”

“As a result of the bargain, the 22 men before the count Tuesday and yesterday were sent home with a judicial warning and their cases placed on file. The six remaining defendants, who will appear before Judge Edward A. Dever today, are expected to get similar treatment.” [“Men Plead ‘Nolo’, All Cases On File,” HARVARD CRIMSON, May 29, 1952.]

The trial hadn’t begun promisingly. The prosecuting attorney asked to try all the defendants together instead of separately and the judge agreed, despite protests from the attorneys representing the students individually. After a long morning of testimony, the judge adjourned the session and called all the defense attorneys into his chambers for a conference.

“‘This trial will last several days of weeks at this rate,’ he said. ‘The situation the night in question was serious, Many might have been hurt. I am convinced that it did not start deliberately. The group intended to have a rally, but it got out of hand. The police did good work and saved many injuries.'”

“‘I am satisfied that these men did not intend any harm. They are all without criminal records. Many have futures in which criminal records would be harmful. There has, of course, been much expense to the state already. I’m asking the court to forget that, too. I’ve spoken to the University deans and to Chief Patrick Ready. They have been in co-operation in the past. If this trial were to go on. It might cause a serious break between them.'”

“‘I think the situation can be worked out. Therefore, I want you to put all these cases on file.'”

“[Police Chief Patrick J.] Ready also promised the several of the officers present during the Pogo uprising will be reprimanded.”

“After the trial, police officers and students talked and joked together in the lobby. One undergraduate was heard to say as he left the building, ‘this is the way the rumpus ends, not with a bang but a whimper,’ But all involved expressed satisfaction at the outcome. The University will not take any action against the participants.” [“Men Plead Nolo,” ibid.]

The remaining six student defendants also pleaded nolo contendere (“no contest) and received the same treatment. Finally, on June 3, the two men who had already been convicted pleaded nolo contendere as well and had their sentences suspended.

Years later, students involved in the case reminisced and provided some insights into the events of May 15, 1952.

“The instigator of the mayhem, students who were here at the time say, was Crimson Managing Editor Laurence D. Savadove ’53, whom two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning writer J. Anthony Lukas ’55 describes as ‘a shrewd cookie.'”

“‘Lukas says, when Savadove told him that he intentionally delayed Kelly’s arrival in the Square, he believed him.”

“‘Larry masterminded the Pogo Riot,’ Lukas says. Savadove, it turns out, picked Kelly up at the airport, but took him for a pit stop at at a bar before driving on to Cambridge.

“‘Savadove deliberately delayed the route so that the crowd would be large and restless,'” says David Halberstam ’55. ‘Something was likely to happen,’ Lukas remembers.” [Belcove, Julie L., “Looking Back 35 Years: The ‘Possum Caused a Riot,” HARVARD CRIMSON, June 9, 1987.]

One participant in the rally was not as forgiving as some of the others.

“”What the [riot] revealed,’ says Ellsberg, ‘was the rage, envy and fury on the part of the police, a hatred for Harvard boys, a chance to beat the shit out of them.'”

Daniel Ellsberg’s (class of 1952) blunt interpretation of events was perhaps indicative of a disdain for authority that would play out two decades later with his release of the U.S. government documents known as the Pentagon Papers.

Meanwhile, Walt Kelly and the “Pogo for President” tour rolled on. He would speak at colleges all over the country in the next few months, gaining support for the pleasant-natured opossum who, undeterred by the nastiness of partisan politics, was resolute in proving that despite the odds against him, he wouldn’t roll over and play dead for anybody.

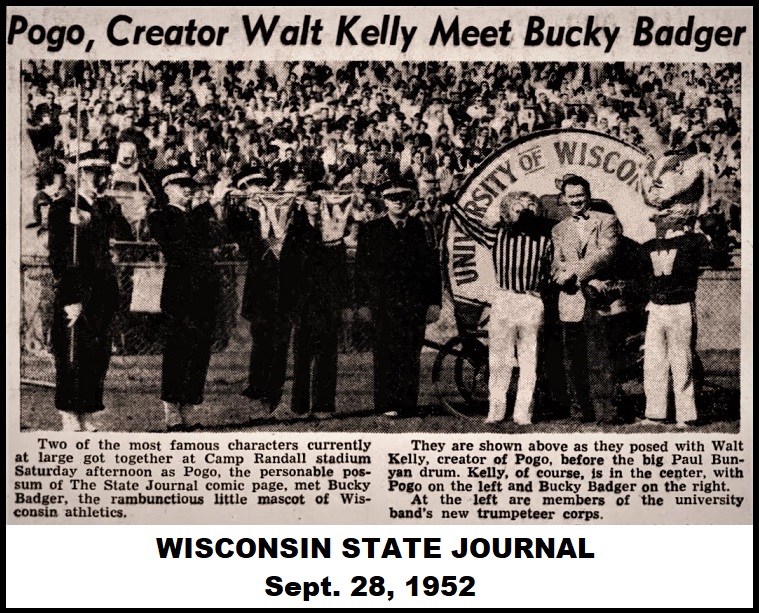

WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL, Sept. 28, 1952