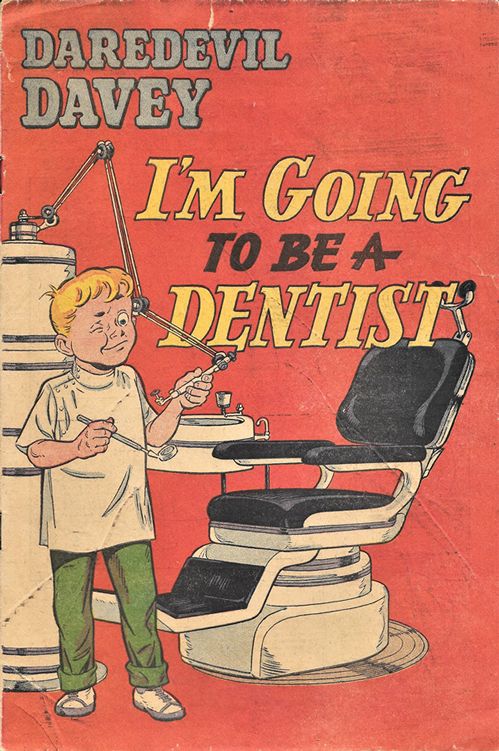

I’M GOING TO BE A DENTIST (1954)

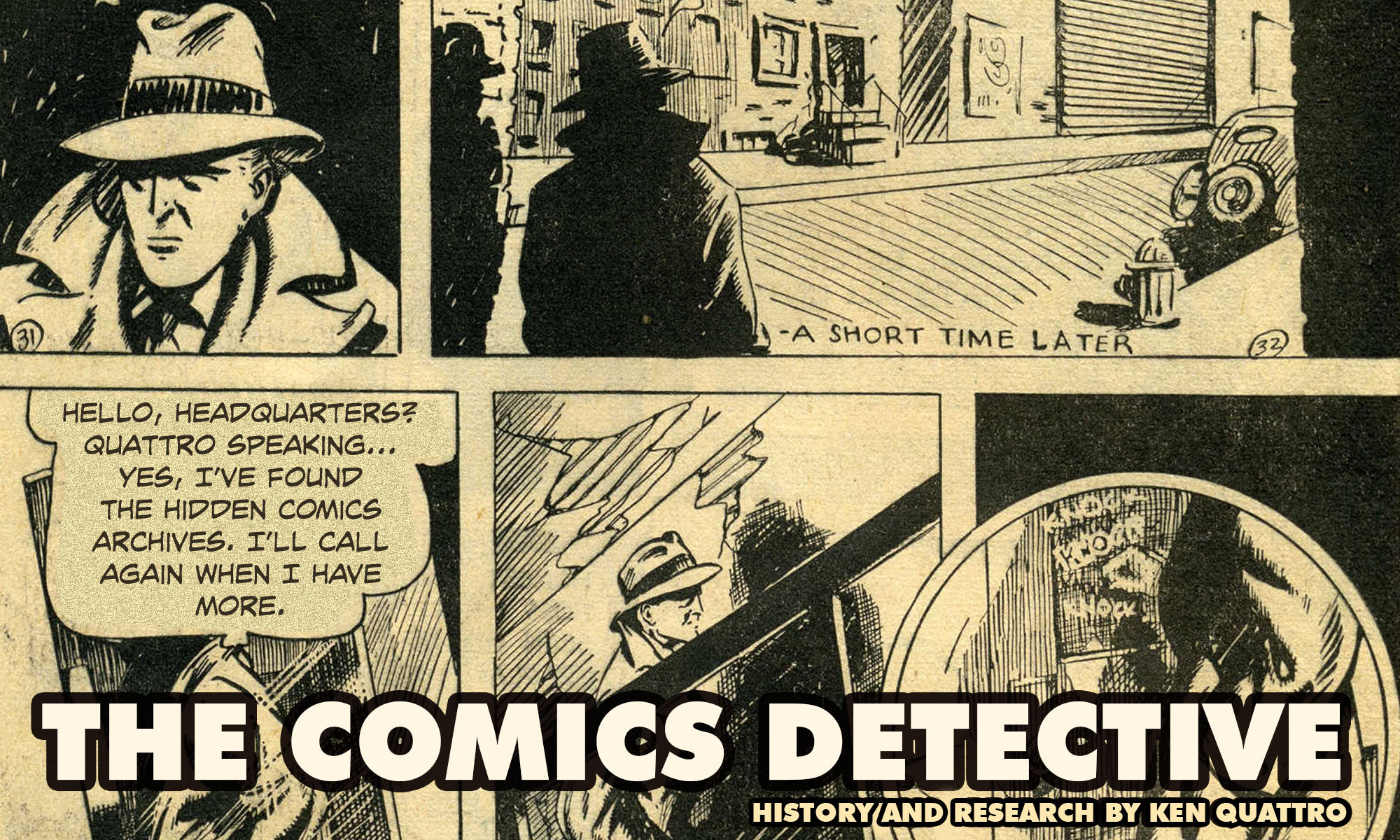

Welcome to the first in a series of what of what I call, CURATED COMICS. The purpose of these articles will be the presentation of underappreciated, little seen or overlooked comic characters, titles, series or even stories, along with background information to help give a reason for their significance and to explain why they were chosen.

©2019 Ken Quattro

Consider the challenge.

Create a comic book concerning one of the most unpleasant experiences a kid will face in their young lives: going to the dentist. No reflection upon dentists, those dedicated protectors of our dental health, but it’s generally an ordeal promising drilling, poking, whirring noises and odd smells. And, yes, sometimes pain.

So, how do you ease a child’s trepidation? Is it possible to make a trip to the dentist–dare I say it–fun?

To be fair, in today’s world, much of the trauma associated with dental appointments is a thing of the past. We have the blessings of newer technologies and drugs to thank for that. But in the early 1950s, all that was decades away and the fears were real.

It’s not clear whether the American Dental Association approached American Visuals Corporation or vice versa. What mattered was that Will Eisner’s commercial comics company had gotten the assignment to create a comic book making the trip to a dentist less stressful.

As was often the case, Eisner then assigned creation of the comic to Klaus Nordling.

Klaus Nordling

Klaus Fjalar Nordling was already a professional cartoonist by the time he began working for Eisner’s comic book shop. Born in Finland in 1910, Nordling had been a freelance cartoonist before becoming the creator of the “Baron Munchausen” daily strip for the Van Tine Features Syndicate in the 1930s under the pseudonym or “Fred Nordley.”

“Baron Munchausen” ad (Dec. 30, 1935)

Eventually, Nordling found his way to Eisner & Iger comic shop, sometime in 1939. By the end of that year, the shop partnership split as did the staff. Nordling went with Eisner and became one of his mainstays. Not only was he involved with producing the “Lady Luck” strip for the “Spirit” Sunday section, but he wrote and drew a number of features for the Quality Comics that were one of the shop’s biggest clients.

“Oh, I worked very close with him [Eisner]. Will Eisner had a tremendous capacity for ideas and a terrific comedy sense. A real satire sense. With a lot of this stuff, when he was with Quality Comics at the same time I was, often what would happen is this: Will was really what you might call the editor or the prime-mover guy, the guiding genius. He’s day, ‘Why don’t you do a new feature for the book?'”

“You realize he did not do this with everybody. He did it with me because we had a certain rapport.” [“The Fabulous ’40s–The First Full Decade Of Comic Books,” Klaus Nordling in panel discussion, July 24, 1966, ALTER EGO #60, pg. 72 (July 2006)]

Nordling’s comic book work is deserving of a full retrospective, but that is not the focus of this article. What is pertinent is that Eisner and Nordling had a symbiotic working relationship that evolved from Eisner’s trust in Nordling’s talents and outlasted their tenure in producing newsstand comic books.

It helped that Nordling’s style complemented Eisner’s own. They both had the ability to tell a story succinctly within the given limitations of a comic book format. A reason for this may well have been their shared interest in theater presentation. Eisner had studied it while attending DeWitt Clinton High School and Nordling wrote, staged and acted in plays throughout his life.

Both creators, as well, brought humor to their work. It wasn’t always out front, often understated, many times lingering in the look of the artwork; applying a lighter tone to an otherwise bleak or serious story. Eisner’s “Spirit” was famous for it, Nordling’s “Lady Luck” and his lesser-known Quality work projected the same ambiance.

American Visuals had came into existence in the late 1940s, as storm clouds were forming around the reputation of newsstand comics. Dr. Fredric Wertham and other critics had begun their attacks upon “bad comics” and the industry as a whole and rather than fight, Eisner avoided the fray and begun producing commercial comic books. It helped that he had also recently failed in his own venture as a newsstand comic book publisher.

The majority of clients for American Visuals in the early 1950s were seemingly mostly from Baltimore, such as the Baltimore Colts football team and the Baltimore Medical Society, continuing a relationship with that city going back to Eisner’s days in the Army during WWII when he was stationed at nearby Aberdeen Proving Grounds. Attracting, and hopefully pleasing, a large national organization like the American Dental Association (ADA) had to be a coup.

Early on, Eisner entrusted Nordling to create some of the material coming out of American Visuals. One notable example was the main story in THE ADVENTURES OF JACK TAR, a giveaway comic intended to help sell an upscale line of children’s clothing. So, when tasked with producing a comic for the ADA, Nordling’s came up with the character of “Daredevil Davey.”

How much of “Daredevil Davey” was Nordling and how much was Eisner, can be divined from Nordling’s later recollection of their working methods.

“[Eisner] called me into the office–he called me at home, but into the office–and say we need a new feature and he’d say, ‘I have an idea. I want this kind and this kind of area, a milieu. Now you dream up a set of characters, and it operates in this particular theater.'”

“Well, I’d go home and I’d figure out some characters and also the first story, and he [Eisner] would say, ‘Well, this is good, this is fine, but let’s change this and change that.'” [Ibid.]

Although Nordling’s words were in reference to his work for Eisner on newsstand comic books, there is no reason to believe that they changed methods when it came to the commercial comics.

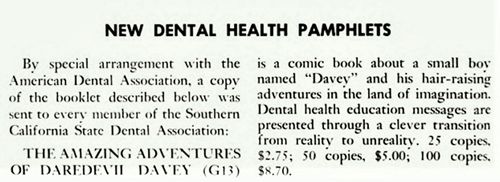

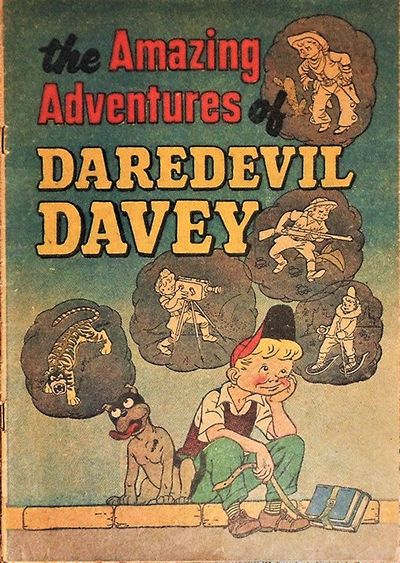

The first appearance of “Daredevil Davey” came in THE AMAZING ADVENTURES OF DAREDEVIL DAVEY, which was released on Sept. 1, 1951, with sample copies distributed to dentists through their state dental associations.

“New Dental Health Pamphlets,” JOURNAL: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA STATE DENTAL ASSOCIATION (Oct. 1951)

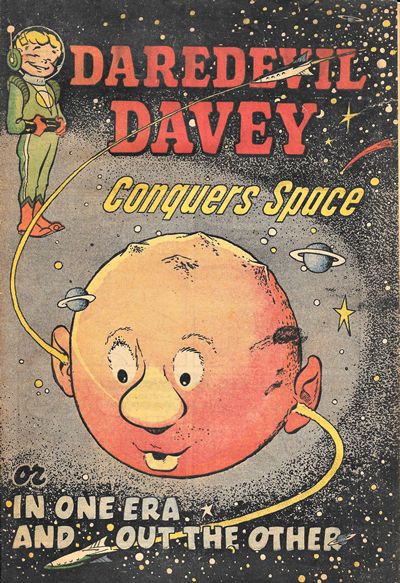

AMAZING ADVENTURES OF DAREDEVIL DAVEY (1951)

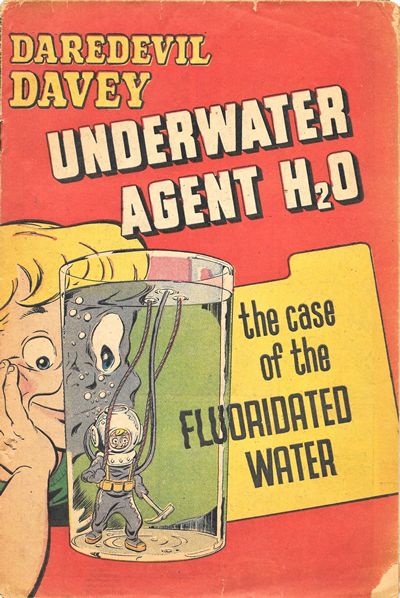

Apparently, the comic was a success. It went into at least two printings, the second coming in 1953 with a print run of 50,000 copies. This success prompted the ADA to order a series of comics starring “Daredevil Davey,” with the first of this series being DAREDEVIL DAVEY UNDERWATER AGENT

DAREDEVIL DAVEY UNDERWATER AGENT H₂O (1953)

The story concerns the then controversial fluoridation of water by communities. Basically, a daydreaming Davey envisions himself as “Agent ,” whose mission was to convince doubters of fluoridation as to its positives.

Davey confronts each of the prevailing naysayers and puts their fears to rest. Nordling’s gorgeous artwork features a different solid-tone color scheme for Davey’s daydreams to differentiate them from his full four-colored his “real” world.

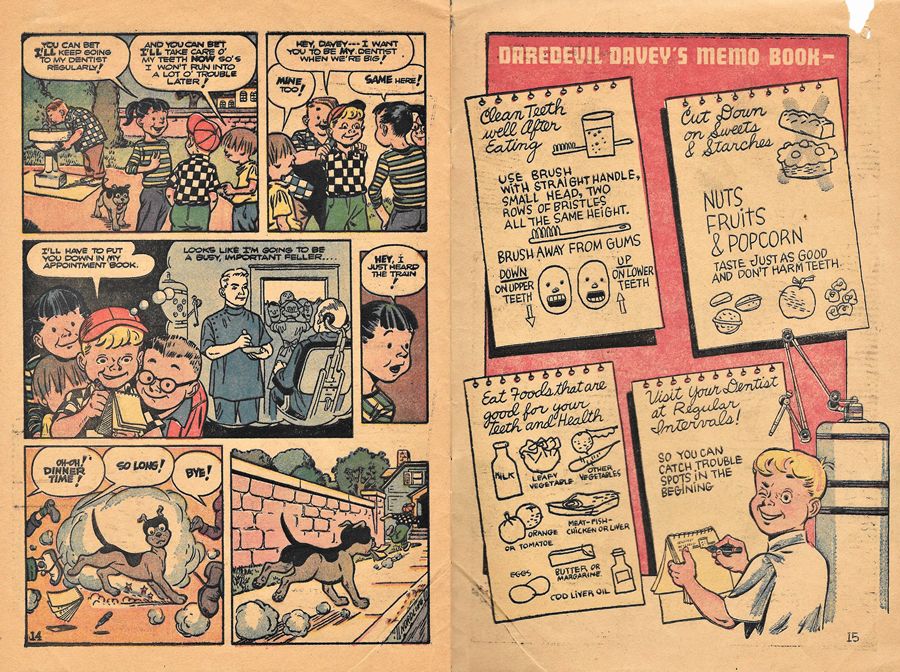

The back cover of this issue depicts four other upcoming “Daredevil Davey” comics: the reprinted THE AMAZING ADVENTURES OF DAREDEVIL DAVEY, DAREDEVIL DAVEY CONQUERS SPACE, I’M GOING TO BE A DENTIST and the never published, DAVEY SHOWS HOW. Why that comic didn’t come to be is unknown.

DAREDEVIL DAVEY CONQUERS SPACE (1953)

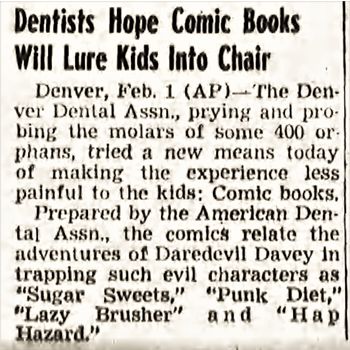

Coordinated with the release of the new comics in the series, a short wire story went out nationwide on Feb. 1, 1954, regarding the use of “Daredevil Davey” comics in the city of Denver.

“Dentists Hope Comic Books Will Lure Kids Into Chair,” (Feb. 1, 1954)

Despite the seemingly obvious popularity of “Daredevil Davey” with children, they weren’t met with the same positivity by teachers. At a 1954 conference involving dental professionals and educators, the latter group made their concerns known.

“The Association materials that were criticized as being of questionable value in the school program were the Daredevil Davey comics and the coloring leaflets for first and second grade children. Although it was pointed out that children’s comics are here to stay and that the Daredevil Davey comics are well written and drawn, the educators preferred other types of material for school use.” [“Teaching Aids Needed,” JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION, vol. 49. pg. 75 (July 1954)]

Eventually, the series stayed in print, with the addition of DAREDEVIL DAVEY ON THE TRAIL, DAREDEVIL DAVEY MAKES THE TEAM and DAREDEVIL DAVEY BREAKS THE TIME BARRIER, all published in 1954.

The “Daredevil Davey” series lasted until 1957, at which time the ADA ended it and began discounting their remaining copies and selling them in bulk quantities. In 1970, the copyright of DAREDEVIL DAVEY BREAKS THE TIME BARRIER seems to have been renewed, but none of the other issues received the same consideration.

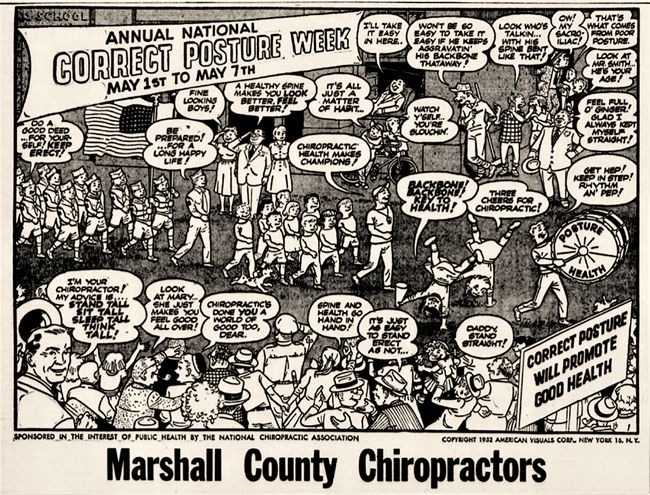

American Visuals would grow its eclectic client list, adding such big names as the Fram Oil Filter company, Girl Scouts of America and the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute. They also produced other health-related comics for the Red Cross and the National Chiropractic Association and its promotion of Correct Posture Week in 1952. The ad for this promotion also featured Nordling’s artwork.

“National Posture Week” ad MARSHALL COUNTY NEWS (May 1, 1952)

For his part, Klaus Nordling continued producing commercial comics through American Visuals throughout the 1950s and according to his 1966 panel appearance, he continued working in the area of commercial illustration afterward. And as he had throughout his comics career, Nordling pursued his passion for the stage in the region surrounding his home in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

WILTON BULLETIN (Nov. 16, 1955)

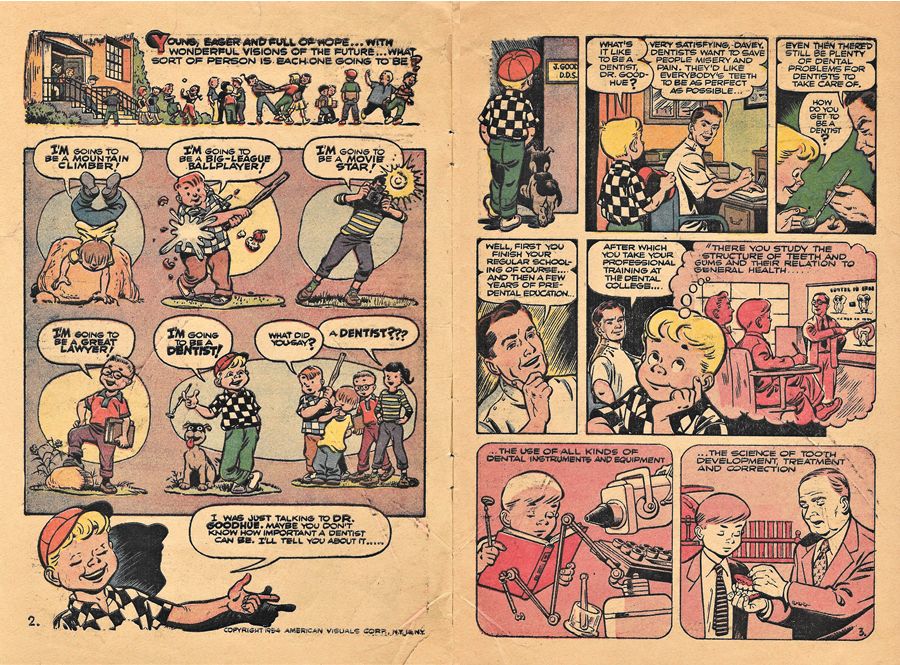

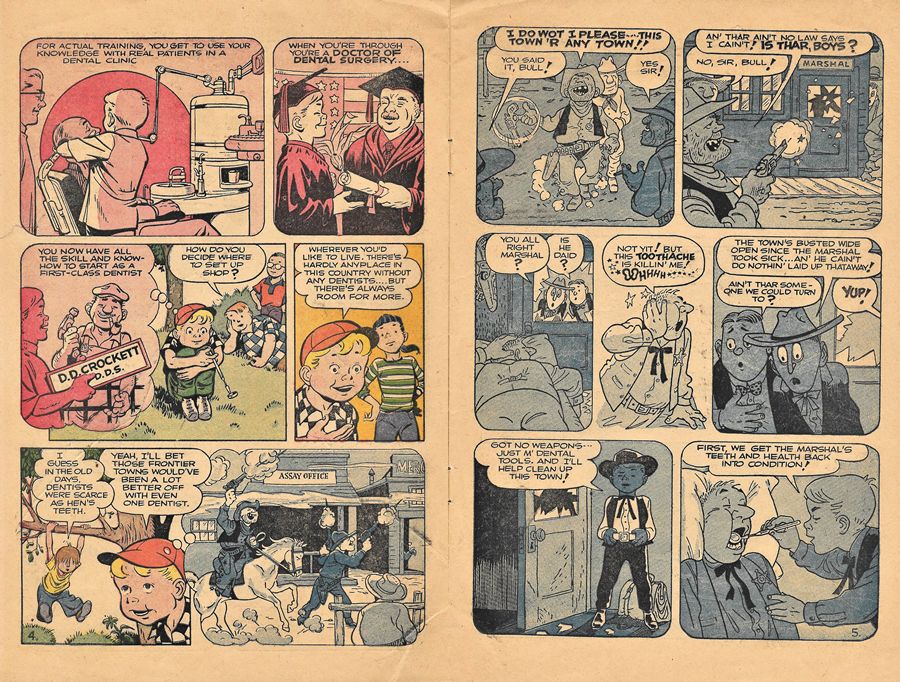

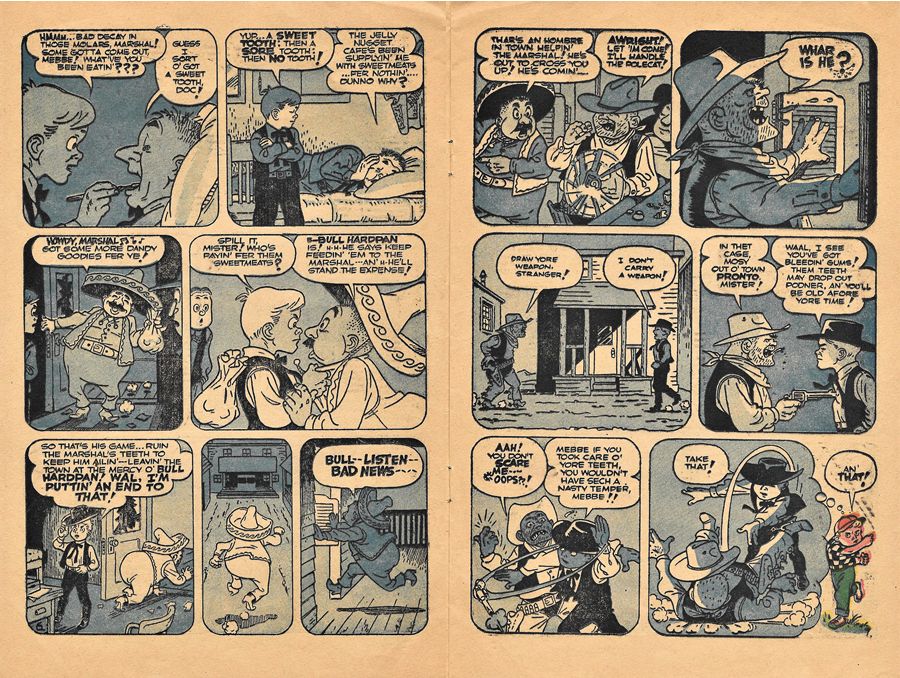

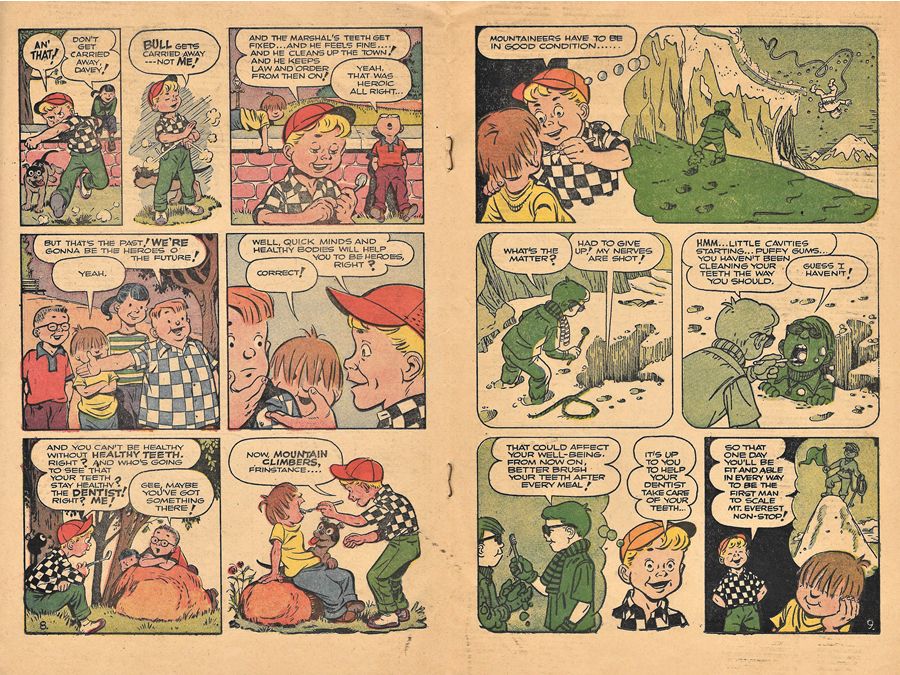

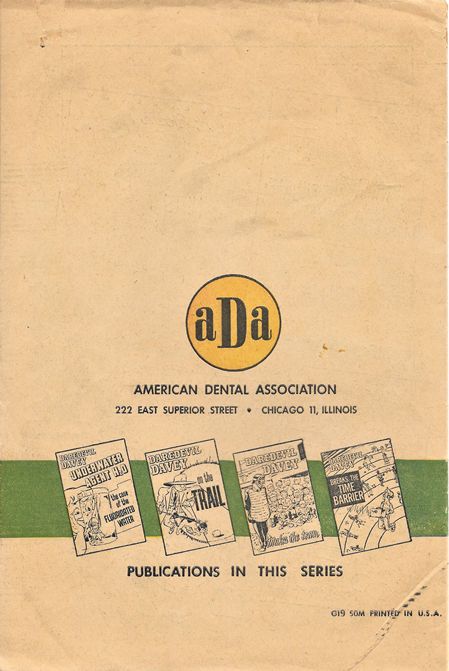

Below are scans of the entire comic, DAREDEVIL DAVEY I’M GOING TO BE A DENTIST (1954). The premise of this story was that young Davey D. Crockett (yes, that was his name) daydreamed about a dental career after talking to his family dentist. As before, Davey’s daydreams appear in solid-colored panels to set them apart from his “real” world. The story is witty and charming and could make a child’s visit to the dentist painless. Almost.

pgs. 2-3

pgs. 4-5

pgs. 6-7

pgs8-9

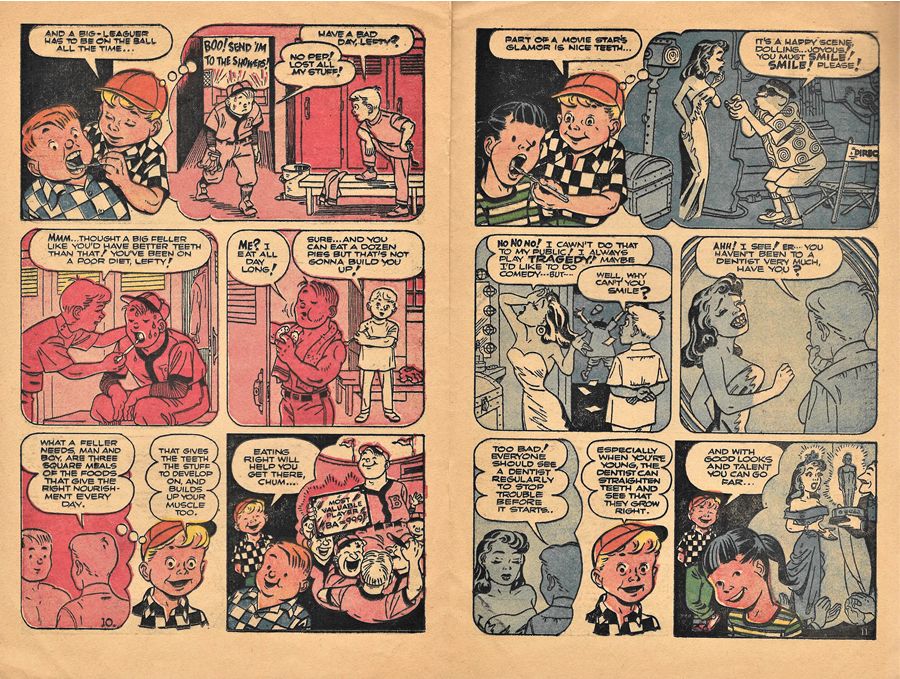

pgs. 10-11

pgs. 12-13

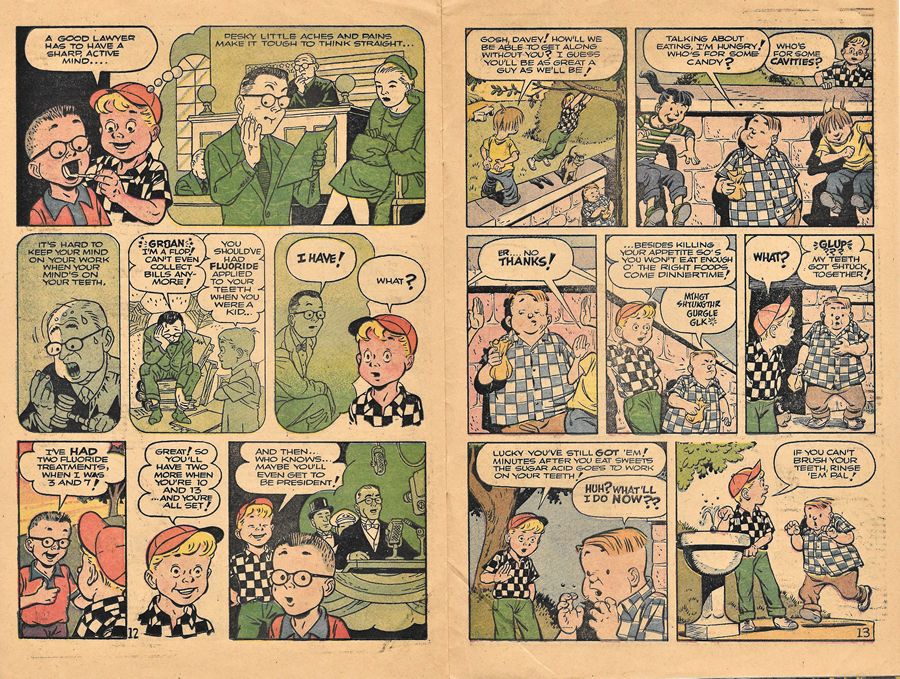

pgs. 14-15

Back cover

2 Comments; ?>

Looking at The Barker, I always wondered how much of an influence Nordling was on Eisner’s first page splash (and vice vers). He certainly was just as good at them as Eisner. The Barker splashes are up there with those for The Spirit in my opinion.

I agree, Ger! Nordling was a terrific talent in his own right and Eisner knew it. He allowed Nordling to do his own thing and it showed in the work. Like Nordling said in the panel discussion in 1966–Eisner was like a director and he knew how to get the most out of his artists.