©2020 Ken Quattro

Definitions: Nikkei are Japanese immigrants of any generation. Nisei are second generation Japanese immigrants who are citizens of another country. Sansei are the third generation of Japanese immigrants who are citizens of another country.

__________________________________

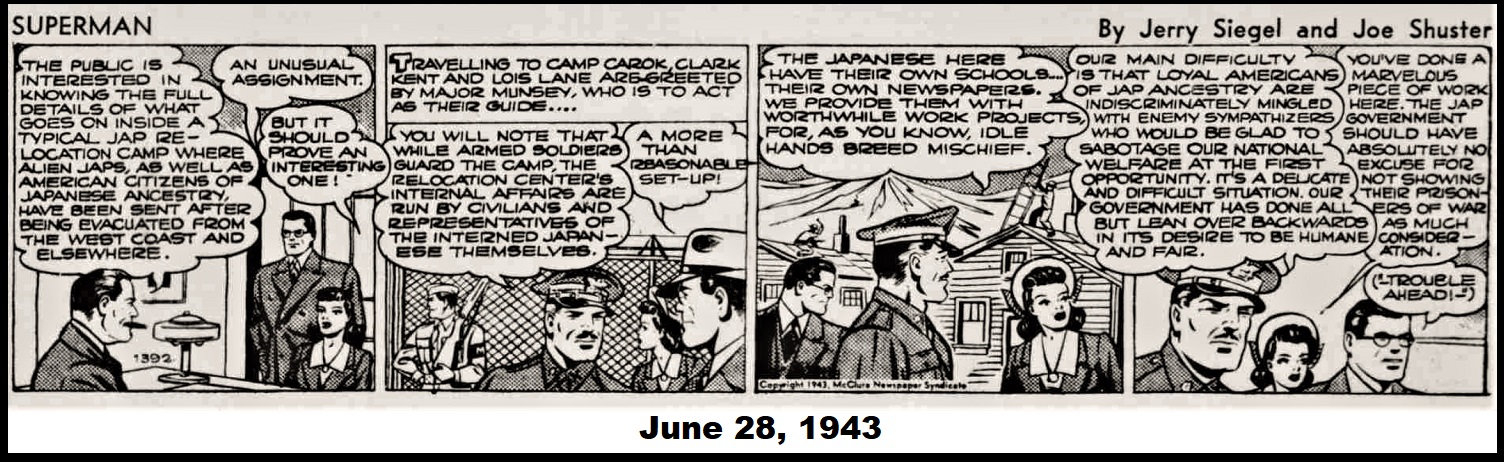

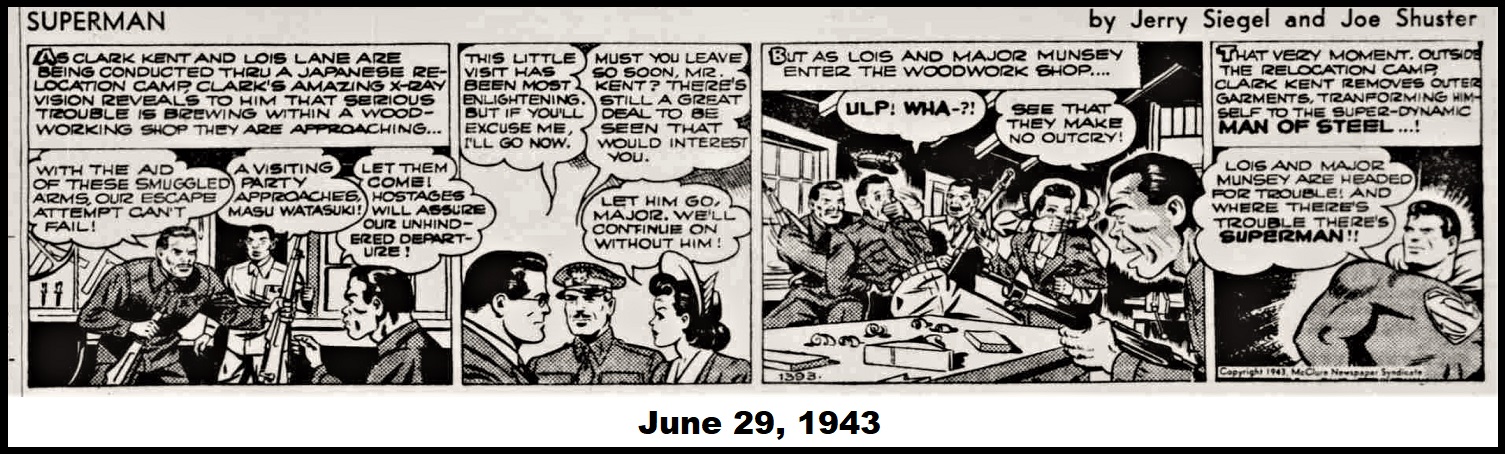

Most American comic strip fans opening their newspaper on Monday, June 28, 1943, and reading the Superman strip for that day, would think little more of it than as the beginning of a new adventure for the Man of Steel.

However, a Japanese-American sitting in a relocation camp and reading it probably had an uneasy feeling about what was to come next. They had reason to be wary.

[Major Munsey to Clark Kent and Lois Lane] “Our main difficulty is that loyal Americans of Jap ancestry are indiscriminately mingled with enemy sympathizers who would be glad to sabotage our national welfare at the first opportunity. It’s a delicate and difficult situation. Our government has done all but lean over backwards in its desire to be humane and fair.”

[Lois replies] “You’ve done a marvelous piece of work here. The Jap government should have absolutely no excuse for not showing their prisoners of war as much consideration.”

[Clark thinks to himself] (–Trouble ahead!–)

The trouble was that the Japanese-Americans interned in the relocation camps were not prisoners of war. They were simply American citizens whose only crime was being of Japanese descent.

June 28, 1943

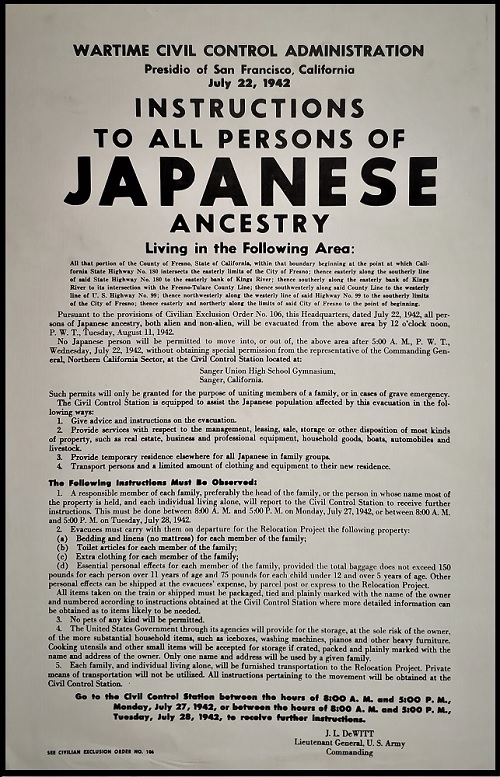

In the days immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor by the combined Japanese air and naval forces, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors feared an internal threat of sabotage from certain nationalities related to the Axis powers, which included Italy, Germany and particularly, Japan. To address this fear, Roosevelt signed an executive order early in 1942 that gave permission for the creation of internment camps (euphemistically called “relocation centers”) to contain “resident enemy aliens.”

“Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.” [United States, Executive Office of the President [Franklin D. Roosevelt]. Executive order 9066: Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas. 19 Feb. 1942.]

While approximately 300 Italian-Americans were eventually interned and 11,000 German-Americans, there were as many as 120,000 Japanese-Americans held in these so-called “relocation camps.”

Poster ordering Japanese-Americans to report for relocation, July 22, 1942

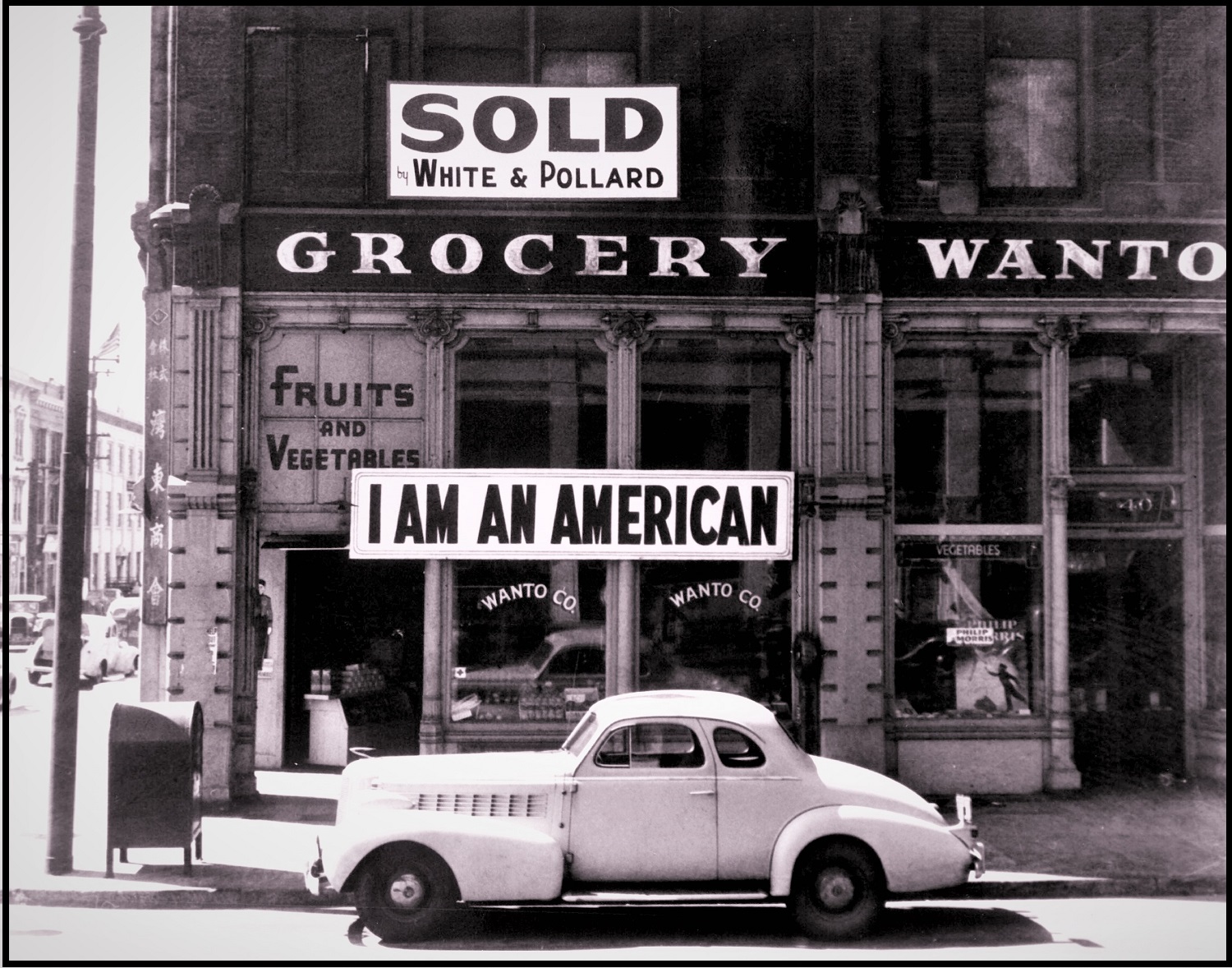

Dorothea Lange photo of a Japanese-American owned store in Oakland, California after the store was closed and the owner moved to a relocation camp. (March 1942)

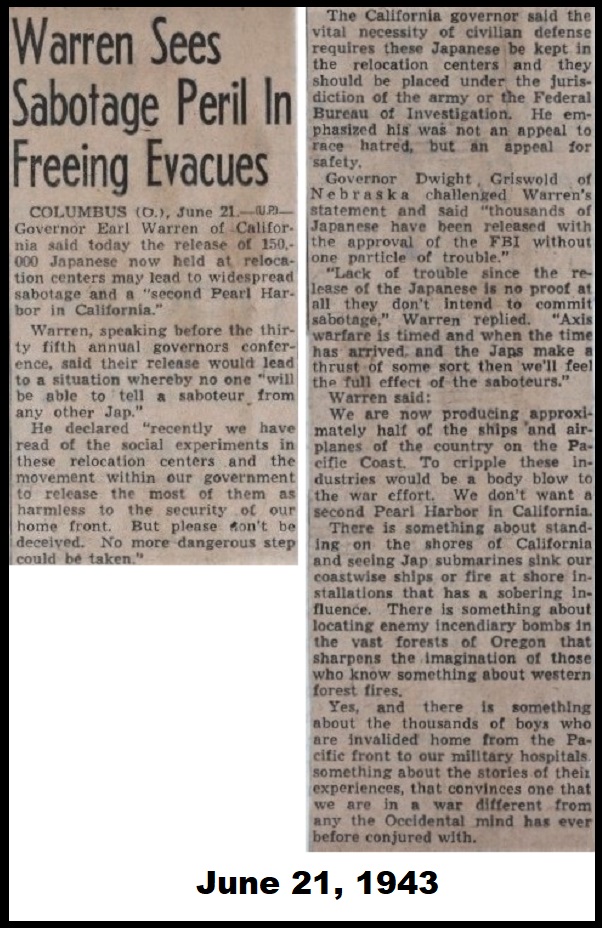

Japanese-Americans awaiting evacuation from Los Angeles to Manzanar internment camp, circa 1942

The forced relocations of Japanese-Americans met little criticism from their fellow Americans. Ideological opposites found themselves on the same side of this issue. Democratic Congressman Martin Dies of Texas, the powerful right wing head of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), held hearings and released a report in June 1943 accusing the War Relocation Authority (WRA) of releasing 12,000 “disloyal” internees from the camps. Governor Earl Warren of California (and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) warned that the release of the incarcerated Nikkei “may lead to widespread sabotage and a ‘second Pearl Harbor in California.'” [“Warren Sees Sabotage Peril in Freeing Evacuees,” June 21, 1943.]

June 21, 1943

Even expected allies, such as many New Deal progressives and left-wingers, approved of the program. Warren G. Magnuson, Democratic Congressman (and future Senator) from Seattle who had many Nikkei among his constituents that had been relocated to Manzanar, reportedly opined that “there were not fifty Japanese among the evacuees who are loyal to this country.” [Shorter, Fred W., Letter to the Editor, SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER, Sept. 21, 1943.]

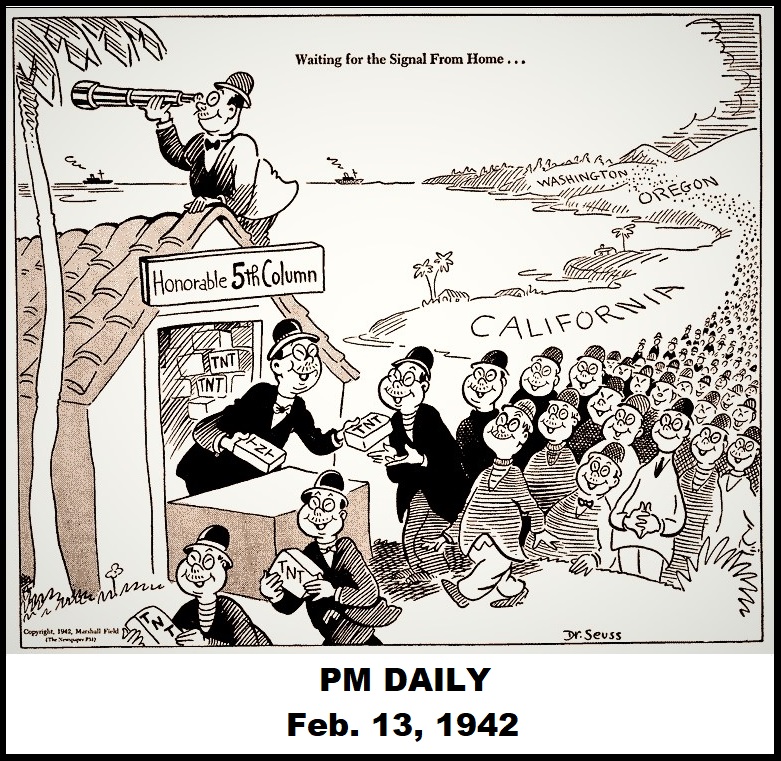

And soon after Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, “Dr. Seuss” (pen-name of the liberal PM DAILY’s editorial cartoonist Theodore Geisel) drew a cartoon expressing his suspicions about Japanese-American treachery.

PM DAILY, Feb. 13, 1942

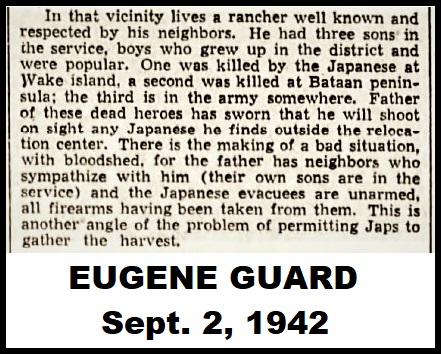

The acrimony of the politicians and the press was reflective of the public as a whole. Many citizens found no differentiation between the Japanese nation that bombed Pearl Harbor and the Americans of Japanese ancestry who were their neighbors. When it was suggested that internees be used as help for the farmers located nearby the relocation camps, it met with a mixed reaction. The farmers needed and appreciated the workers who would replace the farm hands they had lost to war service. Others in their community, though, felt far differently.

EUGENE GUARD, Sept. 2, 1942

“In the vicinity lives a rancher well known and respected by his neighbors. He had three sons in the service, boys who grew up in the district and were popular. One was killed by the Japanese at Wake Island, a second was killed at Bataan peninsula; the third is in the army somewhere. Father of these dead heroes has sworn that he will shoot on sight any Japanese he finds outside the relocation center.” [Kelly, John W., “Washington Letter,” EUGENE GUARD, Sept. 2, 1942.]

With all this as a backdrop, it was understandable if a Japanese-American living in one of the relocation camps read the Superman daily of June 28, 1943, with some trepidation. The strips that followed confirmed their worst fears.

June 29, 1943

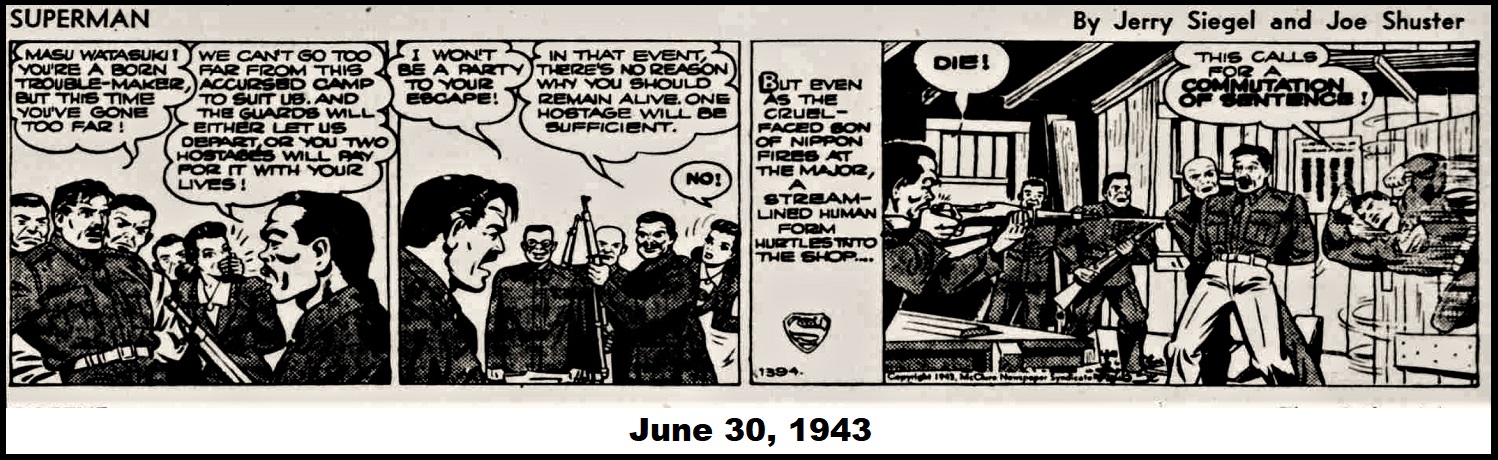

June 30, 1943

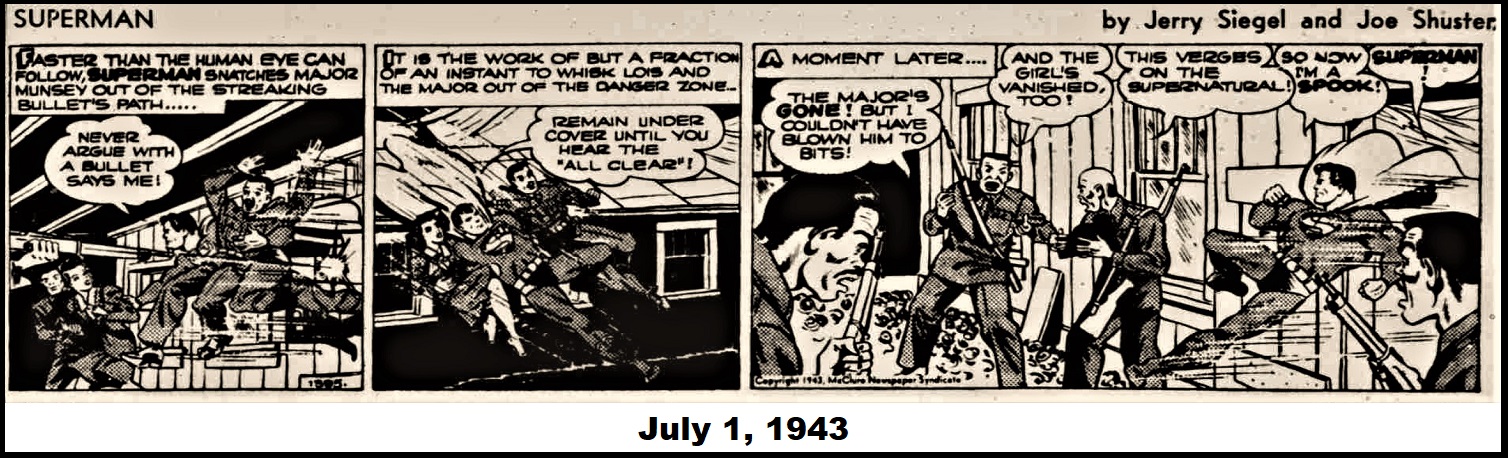

July 1, 1943

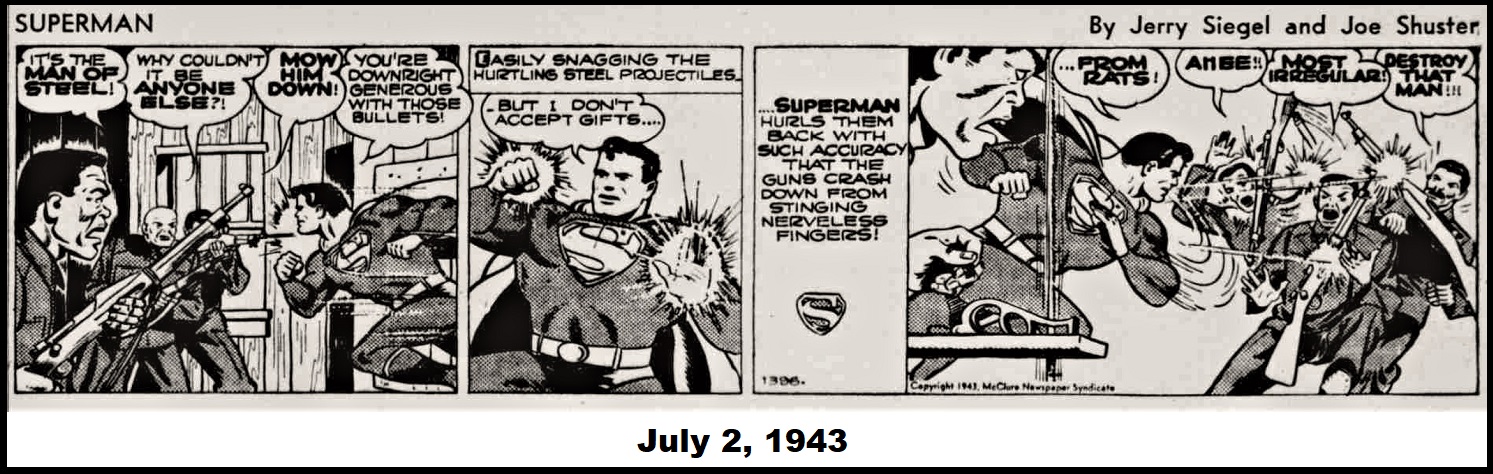

July 2, 1943

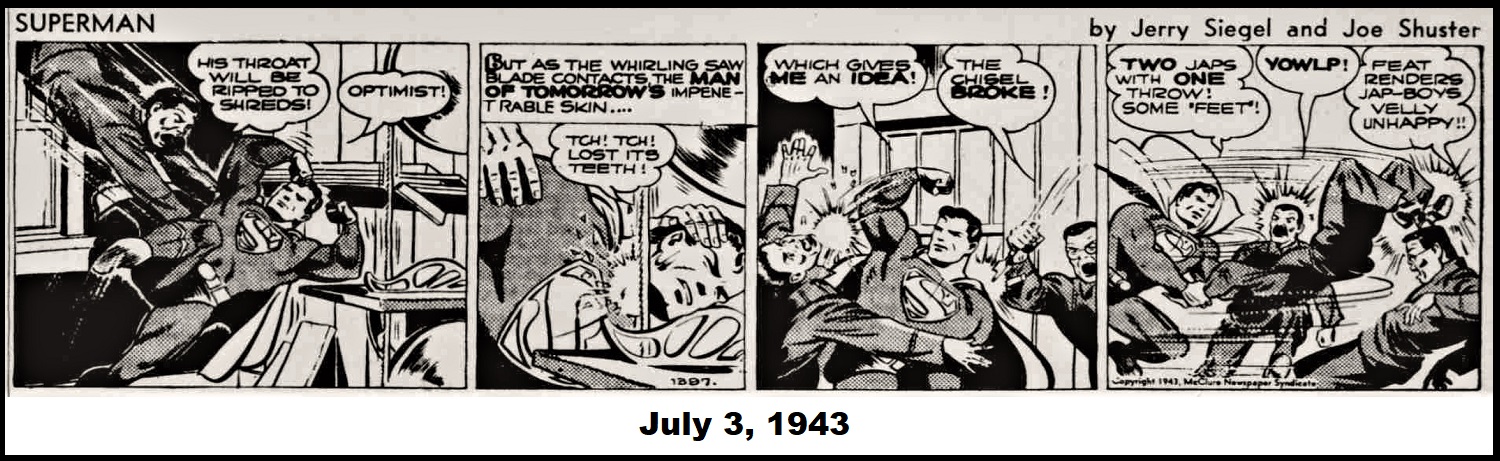

July 3, 1943

As the nation celebrated Independence Day, the patriotic holiday probably seemed a bit hollow to internees reading the concurrent Superman continuity. Presumably, those Nikkei who were Superman fans were especially disheartened.

“While the underworld and saboteurs quake and quiver in terror of Superman, the Flash, Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman, Heart Mountain youngsters revel in their escapes for comic books sell faster than any other magazine at the Community stores.” [Kaihatsu, Martha, “Reading Tastes Typically American,” HEART MOUNTAIN SENTINEL, Nov. 11, 1942.]

Staff of the MINIDOKA IRRIGATOR, 1943

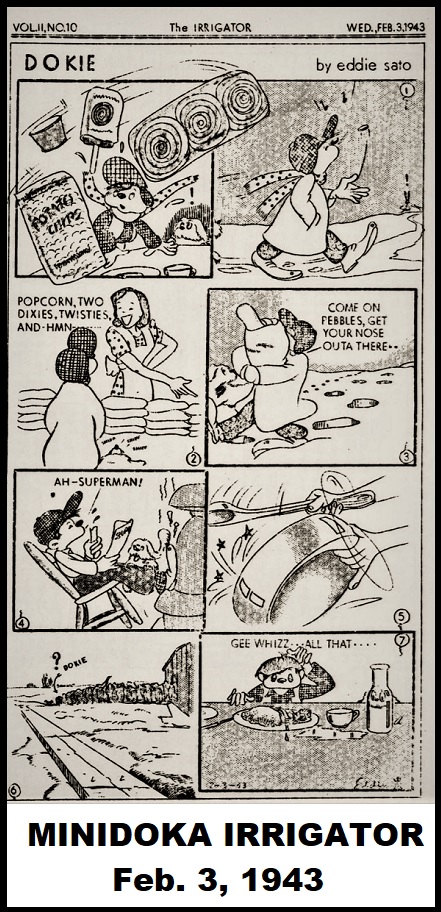

Superman in particular had made an impact on one young aspiring cartoonist among the evacuees. Eddie Sato, who resided in Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho, was the staff artist on the MINIDOKA IRRIGATOR. In late 1942, Sato created a comic strip that featured an unnamed young Nisei. In an article accompanying the announcement of this strip, readers were asked to provide a name for the character, who frequently was found with “his nose buried in the Superman comics.” [“Name Sought for ‘Imp’ Who Makes Debut,” MINIDOKA IRRIGATOR, Oct. 21, 1942.]

Indeed, Sato’s strip often included a panel wherein the newly-dubbed “Dokie” would be seen relaxing in a chair reading a Superman comic book.

MINIDOKA IRRIGATOR, Feb. 3, 1943

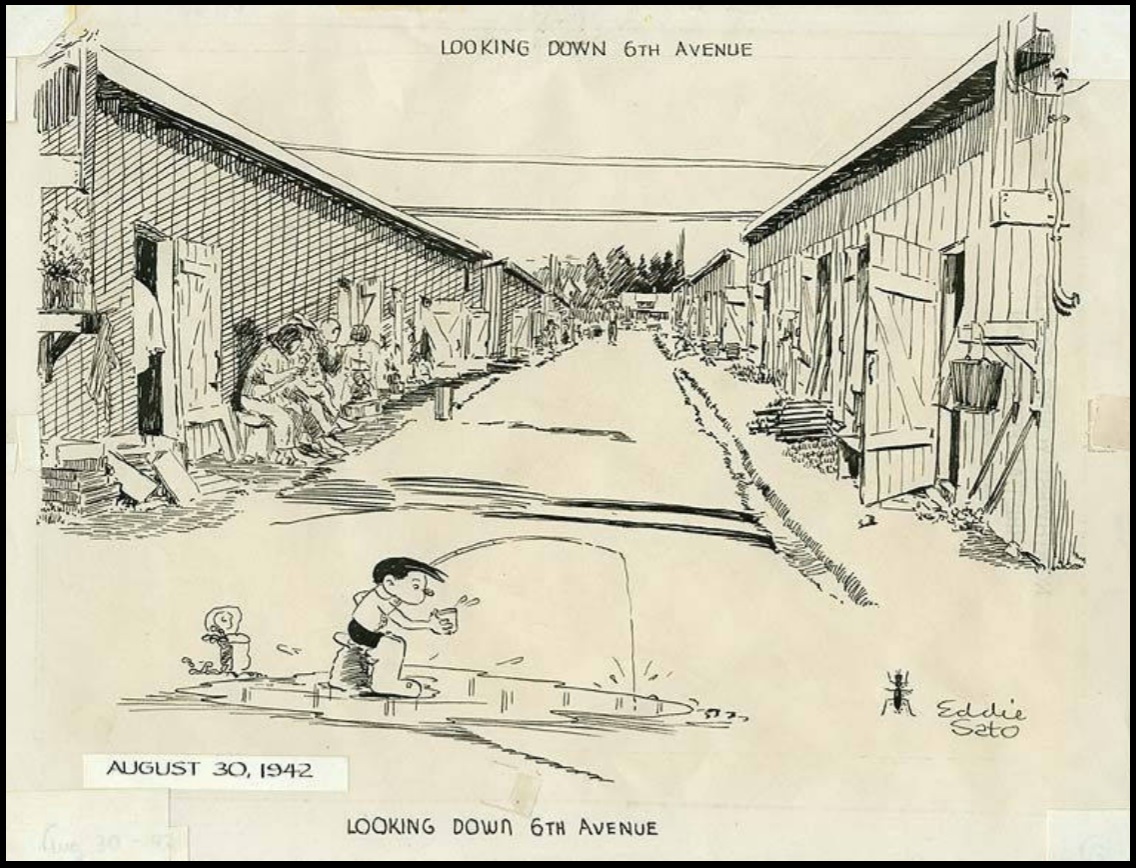

Sato had come to Minidoka by way of “Camp Harmony,” the name given unironically to the Puyallup Assembly Center in Washington, the converted fairgrounds site where he had been incarcerated at the age of 19 in 1942, along with 7,390 other Nikkei awaiting permanent resettlement.

Eddie Sato sketch of “Camp Harmony,” Aug. 30, 1942

Sato was drafted in May 1943, before he was able to comment upon the Superman comic strip controversy, and was assigned to the all-Japanese-American 442nd Combat Team. After training at Camp Shelby in Mississippi, he was sent along with the rest of the division to fight in Italy.

There was no shortage of commentary, however, from other Nikkei. Newspapers in almost all of the ten relocation camps ran articles addressing the Superman story-line with varying degrees of anxiety and hope.

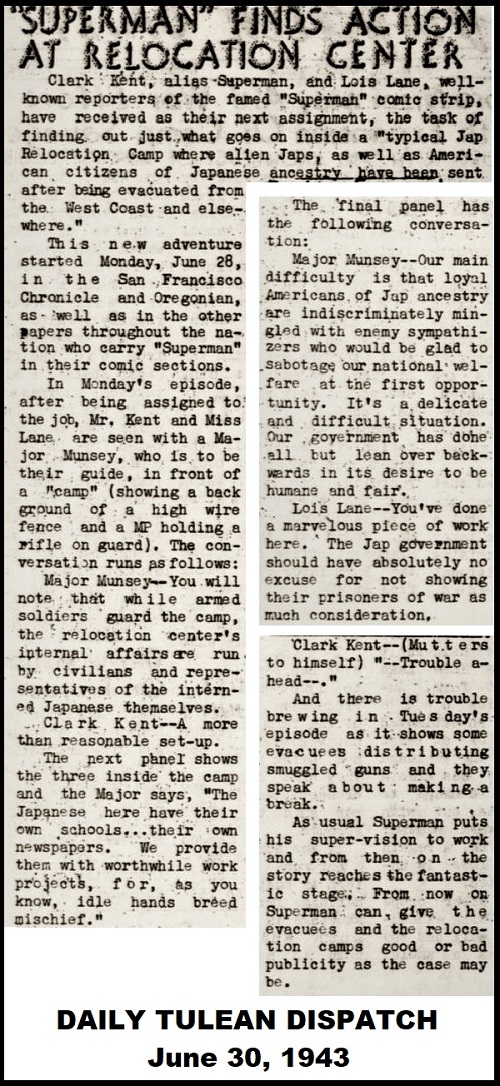

One of the first to comment was a writer for the DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH. After a lengthy recap of the first sequence of June 28th, the writer ended the article on a cautious note.

DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH, June 30, 1943

“From now on Superman can give the evacuees and the relocation camps good or bad publicity as the case may be.” [“Superman Finds Action At Relocation Center,” DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH, June 30, 1943.]

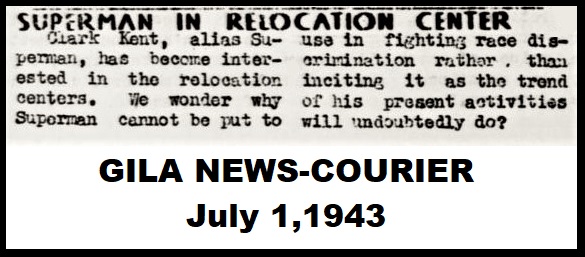

The GILA NEWS-COURIER was less circumspect about expressing their concerns.

GILA NEWS-COURIER, July 1, 1943

“We wonder why Superman cannot be put to use in fighting race discrimination rather than inciting it as the trend of his present activities will undoubtedly do? [“Superman in Relocation Center,” GILA NEWS-COURIER, July 1, 1943.]

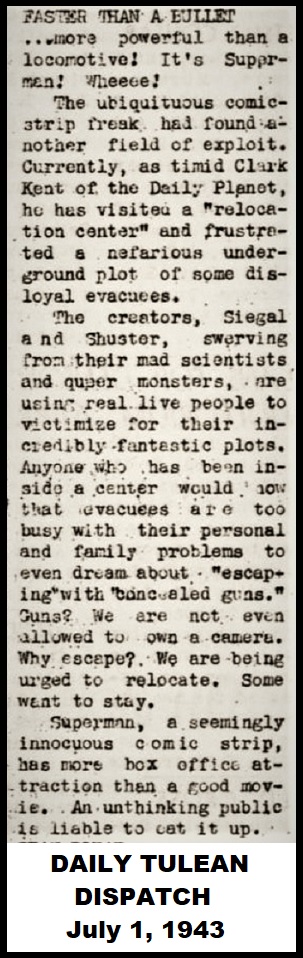

DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH, July 1, 1943

That same day, the Tule Lake, California camp newspaper ran another article about the Superman continuity, and this time, the writer was more direct in their criticism.

“The creators, Siegel and Shuster, swerving from their mad scientists and queer monsters, are using real live people to victimize for their incredibly fantastic plots. Anyone who has been inside a [relocation] center would kn ow that evacuees are too busy with their personal and family problems to even dream about ‘escaping’ with ‘concealed guns.’ Guns? We are not even allowed to own a camera.” [“Faster Than a Bullet,” DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH, July 1, 1943.]

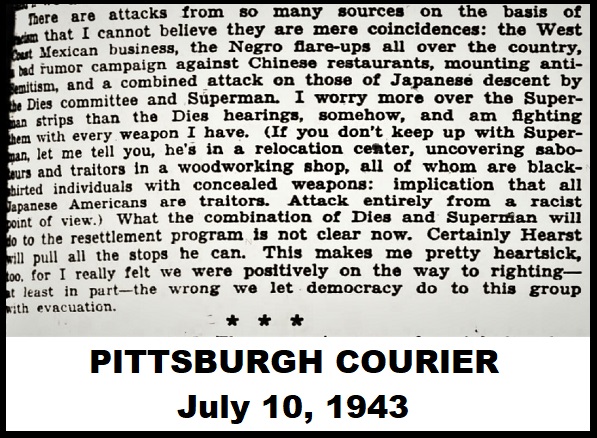

Although the Nikkei evacuees had few supporters, particularly in the western states, they did have some. One who spoke out was M. Margaret Anderson, a writer and editor of COMMON GROUND, a literary magazine that featured the work of writers from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Anderson’s thoughts about the Superman strip appeared in the PITTSBURGH COURIER, a prominent Black-owned newspaper.

“There are attacks from so many sources on the basis of racism that I cannot believe they are mere coincidences: the West Coast Mexican business, the Negro flare-ups all over the country, the bad humor campaign against Chinese restaurants, mounting anti-Semitism, and a combined attack on those of Japanese descent by the Dies committee and Superman. I worry more over the Superman strips than the Dies hearings, somehow, and am fighting them with every weapon I have. (If you don’t keep up with Superman, let me tell you, he’s in a relocation center, uncovering saboteurs and traitors in a woodworking shop, all whom are black-shirted individuals with concealed weapons: implication that all Japanese Americans are traitors. Attack entirely from a racist point of view.) What the combination of Dies and Superman will do to the resettlement program is not clear now. Certainly [William Randolph] Hearst will pull all the stops out he can. This makes me pretty heartsick, too, for I really felt we were positively on the way to righting–at least in part–the wrong we let democracy do to this group with evacuation.” [Anderson, M. Margaret, “Racism: Cause and Cure,” PITTSBURGH COURIER, July 10, 1943.]

PITTSBURGH COURIER, July 10, 1943

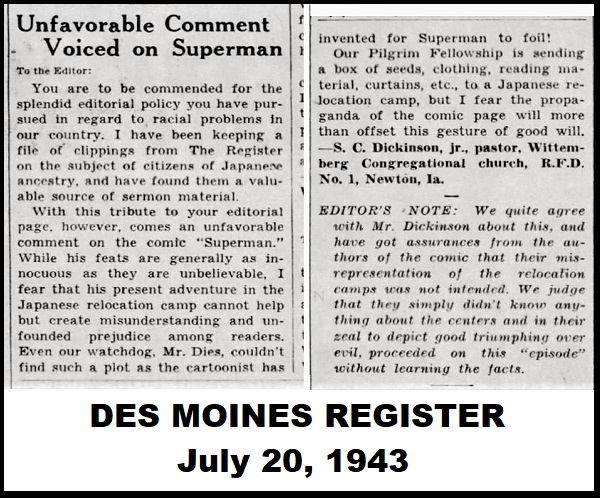

Notably, there was barely any mention of the controversy in mainstream white newspapers. One of the rare comments came in a letter to the editor of an Iowa paper from a local minister.

“I fear that his present adventure in the Japanese relocation camp cannot help but create misunderstanding and unfounded prejudice among readers. Even our watchdog, Mr. Dies, couldn’t find such a plot as the cartoonist has invented for Superman to foil!” [“Unfavorable Comment Voiced on Superman,” DES MOINES REGISTER, July 20, 1943.]

DES MOINES REGISTER, July 20, 1943

The responding editor agreed with the pastor and relayed the information that they “got assurances from the authors of the comic that their misrepresentation of the relocation camps was not intended.” [“Unfavorable,” ibid.]

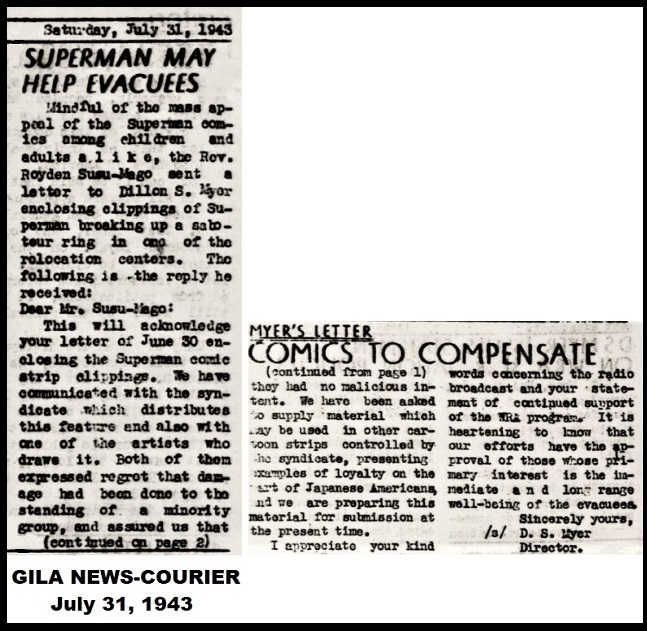

It didn’t take long for these concerns to reach the upper levels of the WRA. The program was already undergoing attacks from Congressman Dies and others for perceived failings and any adverse publicity was definitely unwanted. Dillon S. Myer, Director of the WRA, even responded to one complaint about the Superman strip that was reprinted in the Gila River, Arizona camp paper.

“We have communicated with the syndicate which distributes this feature and also with one of the artists who draws it. Both of them expressed regret that damage had been done to the standing of a minority group, and assured us that they had no malicious intent. We have been asked to supply material which may be used in other cartoon strips controlled by the [McClure] syndicate, presenting examples of loyalty on the part of Japanese Americans, and we are preparing this material for submission at this present time.” [“Superman May Help Evacuees,” GILA NEWS-COURIER, July 31, 1943.]

GILA NEWS-COURIER, July 31, 1943

Unbeknownst to Rev. Susu-Mago, recipient of Myer’s reply, the WRA was already well aware of the offending story-line of the Superman strip even before it had been published.

Philleo Nash, a professor of anthropology who was serving as a media analyst in the Office of War Information (OWI), saw the Superman strip when it had been submitted by the McClure Syndicate per wartime censorship regulations.

Nash immediately noticed that the story-line involving Superman fighting homegrown Japanese-American saboteurs was going to create problems. The government was desperate to keep the public focused on the positives of the relocation program and the implication that the camps may be harboring treasonous evacuees played right into the hands of those who only saw its failings and wanted more punitive measures taken against the Nikkei.

“Superman is about to visit the war relocation centers.”

“The Superman reference will create new hostility to the work of the War Relocation Authority program. The centers have to be run. No one suggests that there should be no Japanese relocation program. Even the severest critics of the War Relocation Authority admit that there are very large numbers of loyal Japanese in the centers. The task of segregating them is enormously difficult. It will only be made more acute by the portrayal of incidents like this in such a popular medium as comic strips.” [Philleo Nash letter to Palmer Hoyt, June 28, 1943.]

Nash’s letter to Hoyt, who director of the domestic branch of the OWI, showed his concern was for the success of the program more than for the evacuees themselves who were offended. His suggestion to Hoyt was that McClure Syndicate be contacted and impress upon them that “an episode should be added to the present Superman sequence, or later episodes should be created, in which loyal Japanese assist Superman; in which the Japanese Combat Team is mentioned; and in which the absence of sabotage accredited to Japanese both in Hawaii and on the Mainland is mentioned.” [Nash letter to Hoyt, ibid.]

Ironically, at the exact same time this controversy was unfolding, Superman’s owners had other issues to address that were more pressing than the story-line of the comic strip.

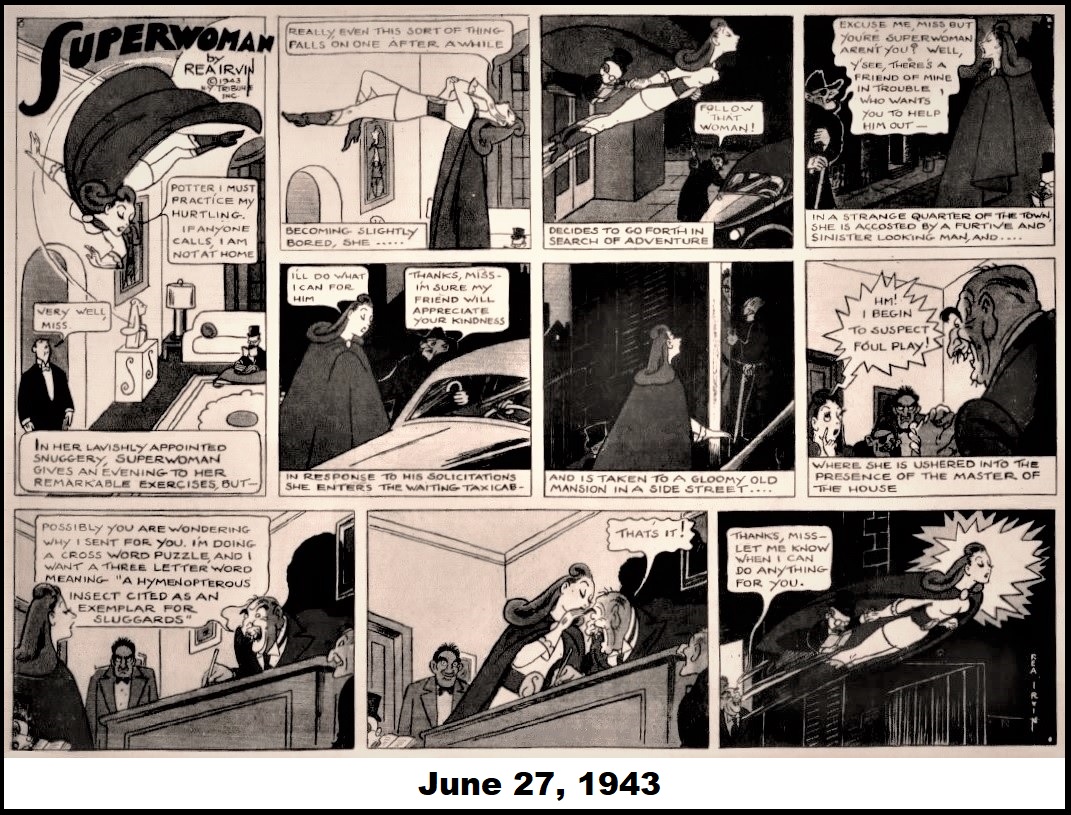

“Yesterday’s Herald Tribune carried a new cartoon feature called ‘Superwoman’ by Rea Irvin. It was the first and last appearance in that gazette. ‘Superman’ threatened suit, and the publisher immediately apologized and said the feature would be withdrawn at once,” [Winchell, Walter, “Walter Winchell on Broadway,” June 28, 1943.]

June 27, 1943

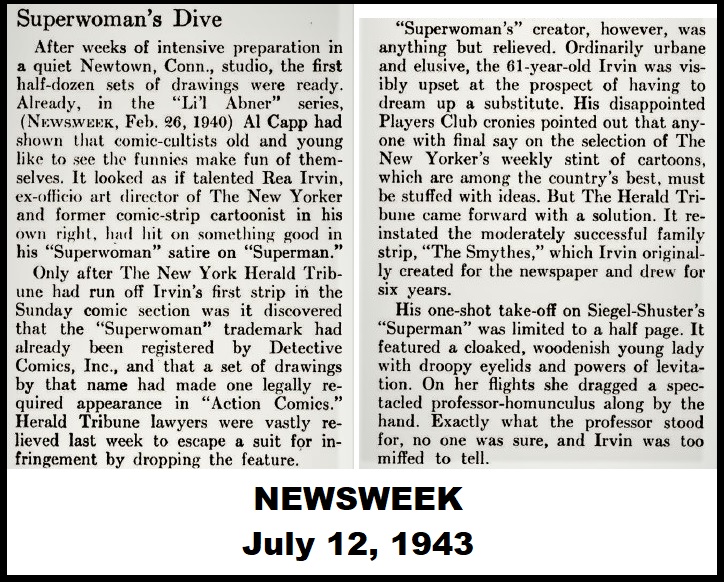

Indeed, the well-known and respected Irvin had made the mistake of not having checked to see if anyone owned the trademark on “Superwoman.” Someone did, and the entire embarrassing affair was told in detail a couple of weeks later in the pages of NEWSWEEK magazine.

“Only after The New York Herald Tribune had run off Irvin’s first strip in the Sunday comic section was it discovered that the ‘Superwoman’ trademark had already been registered by Detective Comics, Inc., and that a set of drawings by that name had made one legally required appearance in ‘Action Comics.’ Herald Tribune lawyers were vastly relieved last week to escape a suit for infringement by dropping the feature.” [“Superwoman’s Dive,” NEWSWEEK, July 12, 1943.]

[note: A story entitled, “Lois Lane–Superwoman!” appeared in ACTION COMICS #60 (May 1943). An appearance used to secure the trademark to the name registered in January 1943.]

NEWSWEEK, July 12, 1943

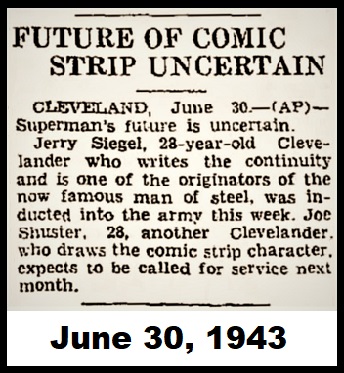

June 30, 1943

Harry Donenfeld, publisher and owner of Detective Comics (DC), had formed Superman, Inc., as a separate entity from DC, to oversee all of Superman’s business affairs. This corporation not only owned the copyright and trademark on the character, it was the publisher of record for his comic book, produced his radio program and cartoons, and licensed everything having to do with him. That is why the second news story of June 28th regarding their franchise star was even more of a concern.

On the same day that the Superman comic strip began the continuity in the relocation camp, Jerry Siegel, Superman’s co-creator and writer, entered the Army. Furthermore, it was made known that Joe Shuster, the other half of the creative team, was to enter the service one month later. So, while the Man of Steel’s bosses could be forgiven for being distracted, it was made clear to them by officials at the OWI and the WRA that the problems created by the comic strip had to be fixed quickly.

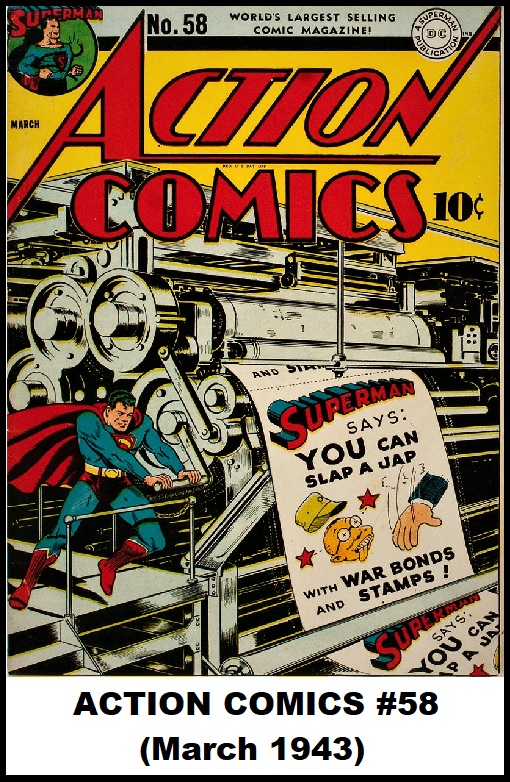

Despite his reputation as the Big Blue Boy Scout, Superman had a problematic history with Japanese people. Not only was he routinely fighting the Axis power in the comics, they were being depicted in the worst way. Just months before the comic strip controversy, the cover of ACTION COMICS #58 (March 1943), showed Superman running a large printing press, churning out posters that read, “Superman Says: You Can Slap A Jap With War Bonds And Stamps!” which featured a hand literally slapping the face of a Japanese soldier. A face drawn in the stereotypical racist Asian style.

ACTION COMICS #58 (March 1943)

Of course, this depiction was de rigueur for comics of the war era, and that was part of the problem. There was little attempt made to differentiate between the Japanese enemy and the Japanese-Americans. The public, angry and vengeful, constantly had to be reminded that there was a difference and the OWI even had to remind the media of the same thing. They were a governmental department and were thinking about the post-war world.

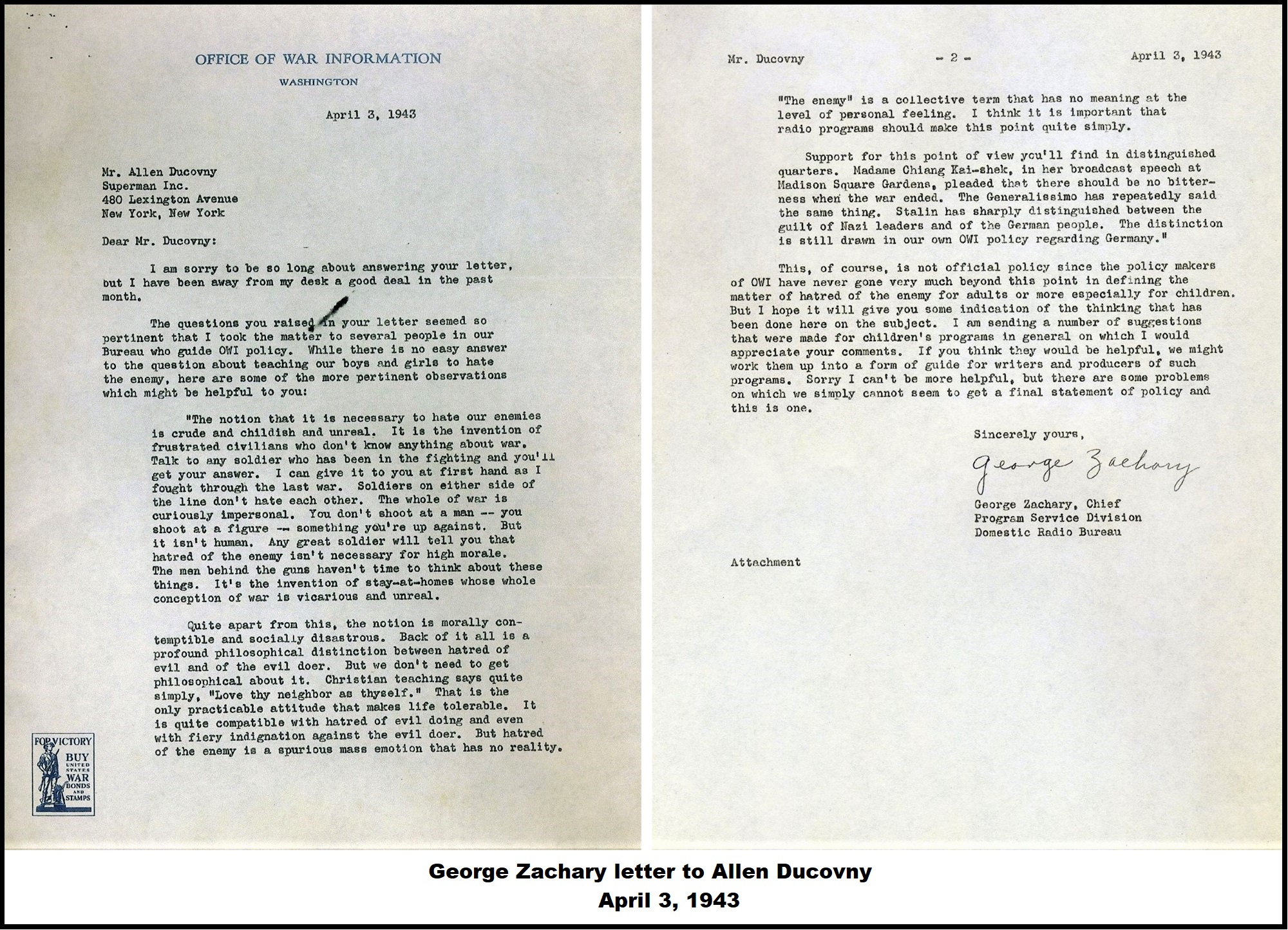

Allen Ducovny, head publicist of Superman, Inc. and co-creator of the Superman radio program with Robert Maxwell, wrote to George Zachary, Chief Program Service Division of the OWI, for guidance on how the producers of the show should go about presenting “the enemy” to children. While his comments were in regard to radio programming, they applied just as well to all media.

“Christian teaching says quite simply, ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself.’ That is the only practicable attitude that makes life tolerable. It is quite compatible with hatred of evil doing and even with fiery indignation against the evil doer. But hatred of the enemy is a spurious mass emotion that has no reality.”

“‘The enemy’ is a collective term that has no meaning at the level of personal feeling. I think it is important that radio programs should make this point quite simply.” [George Zachary letter to Allen Ducovny, April 3, 1943]

George Zachary letter to Allen Ducovny, April 3, 1943

Despite the uncompromisingly negative and often racist depictions in comics and other media, Zachary proposed a more even-handed portrayal of the Axis. He quoted other, unnamed “policy makers” working within the OWI, and sent along suggestions to guide the Superman program’s producers.

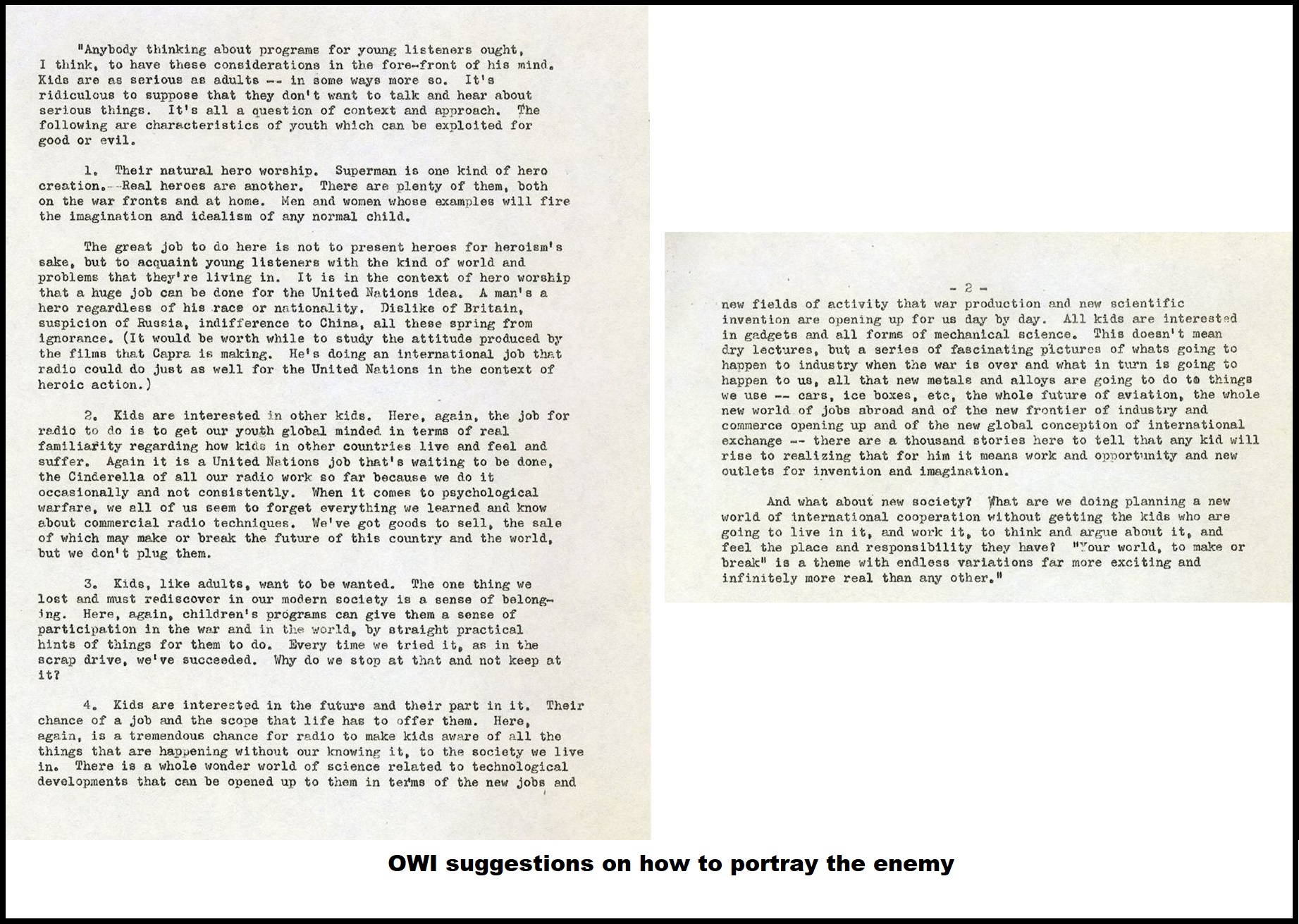

OWI suggestions on how to portray the enemy (1943)

“[Children’s] natural hero worship. Superman is one kind of hero creation. Real heroes are another. There are plenty of them, both on the war fronts and at home. Men and women whose examples will fire the imagination and idealism of any normal child.”

“It is the context of hero worship that a huge job can be done for the United Nations idea. a man’s a hero regardless of his race or nationality. Dislike of Britain, suspicion of Russia, indifference to China, all these spring from ignorance.”

“…the job for radio to do is to get our youth global minded in terms of real familiarity regarding how kids in other countries live and feel and suffer. Again it is a United Nations job that’s waiting to be done…” [OWI Suggestions on How to Portray the Enemy to Children, 1943.]

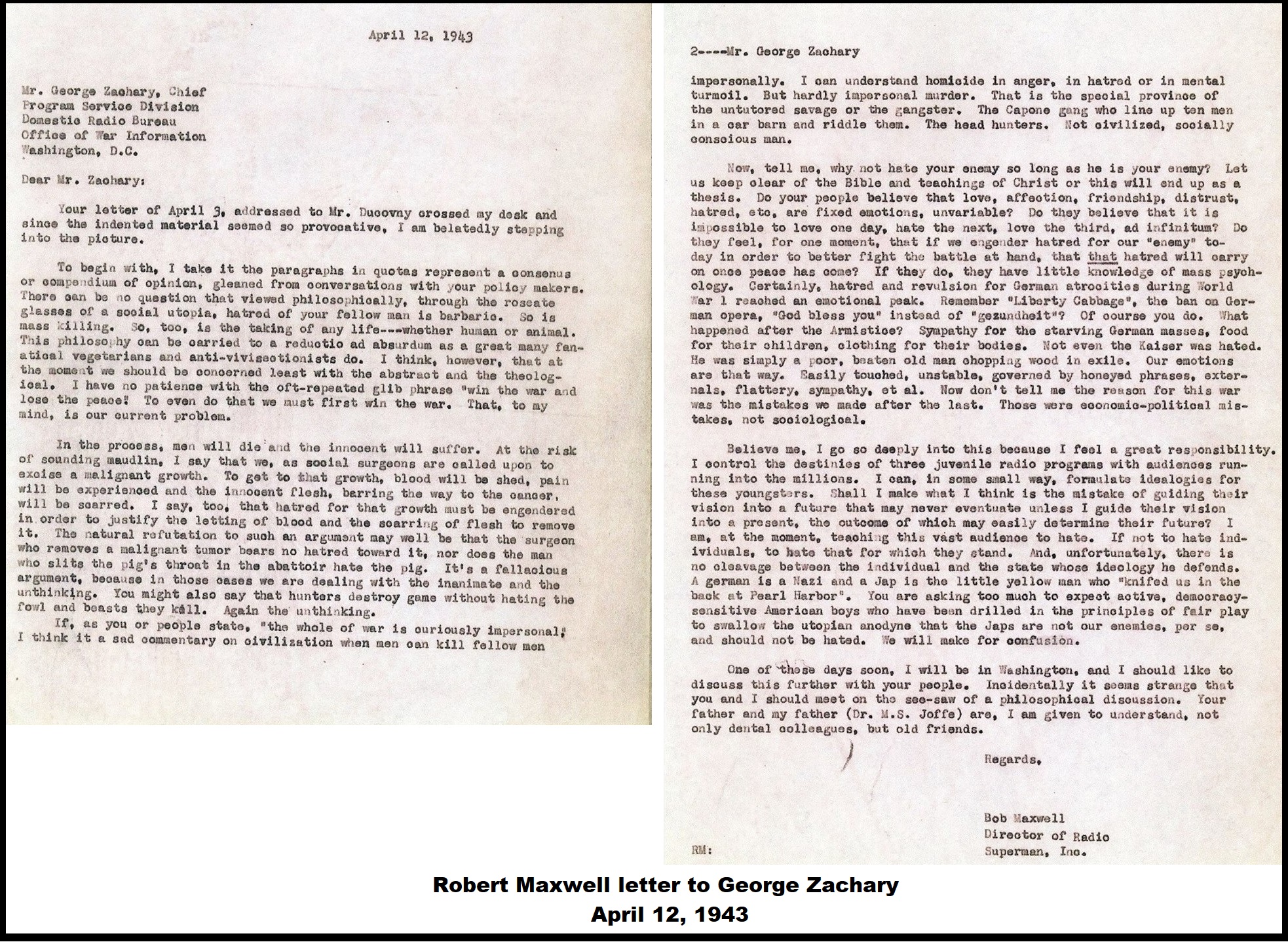

Ducovny didn’t get a chance to reply. Zachary’s letter was intercepted by Maxwell and it’s fair to say he vehemently disagreed with it. Maxwell passionately expressed that he had no concern with “abstract” views, philosophical arguments or post-War consequences.

Robert Maxwell letter to George Zachary, April 12, 1943

“To begin with, I take it the paragraphs in quotes represent a consensus or compendium of opinion, gleaned from conversations with your [OWI] policy makers. There can be no question that viewed philosophically, through the roseate glasses of social utopia, hatred of your fellow man is barbaric. So is mass killing. So, too, is the taking of any life–whether human or animal. This philosophy can be carried to a reductio ad absurdum as a great many vegetarians and anti-vivisectionists do. I think, however, that at the moment we should be concerned least with the abstract and the theological. I have no patience with the oft-repeated glib phrase ‘win the war and lost the peace.’ To even do that we must first win the war. That, to my mind, is our current problem.”

“Now, tell me, why not hate your enemy so long as he is your enemy? Let us keep clear of the Bible and teachings of Christ or this will end up as a thesis.”

“I am, at the moment, teaching this vast audience to hate. If not to hate individuals, to hate that for which they stand. And, unfortunately, there is no cleavage between the individual and the state whose ideology he defends. A german [sic] is a Nazi and a Jap is the little yellow man who ‘knifed us in the back at Pearl Harbor.'” [Robert Maxwell letter to George Zachary, April 12, 1943]

Maxwell eloquently put into words what many Americans were feeling about the enemy. There was no equivocation, no time for philosophic debate or moral introspection. The majority of Americans were thirsty for revenge, particularly on the Japanese who initiated the hostilities by attacking Pearl Harbor. The fact that they were Asian inflamed base racial biases. Biases that were easily redirected at their ethnic relatives who were American citizens.

Maxwell understood the temper of the country and he also spoke for Superman. As one of the top executives in Superman, Inc., he had a voice in how the superhero was presented to the public. Superman was more than a comic book character by this point. He was a franchise, a marketing bonanza and a developing symbolic icon. Maxwell, along with comic book editor Whitney Ellsworth and Josette Frank whom he had originally hired to monitor the content of the radio scripts, were very aware of what was at stake and carefully crafted Superman’s character and gave him moral guidance. Even though they didn’t directly oversee the comic strip, the relocation camp sequence that was now the source of such angst could not have been produced by Siegel and Shuster et. al. without approval.

When the story-line finally came to a conclusion on August 21, it finds Lois and Clark sitting in their office discussing Superman’s victory over the Japanese menace. Then, Superman himself appears in an incongruous final panel that had been grafted onto to the strip to placate the concerned governmental bureaucrats and assuage the feelings of any offended parties.

[Superman speaking to the reader] “It should be remembered that most Japanese-Americans are loyal citizens many are in combat units of our armed forces, and others are working in war factories. According to government statements, not one act of sabotage was perpetrated in Hawaii or territorial U.S. by a Japanese-American.”

Aug. 21, 1943

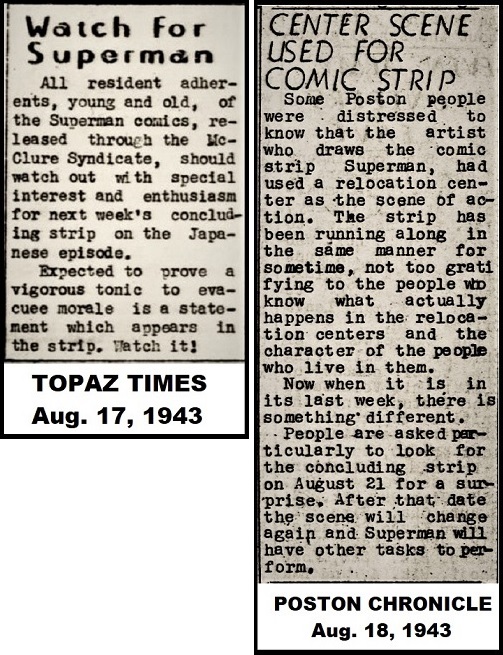

After nearly two months of bashing Japanese-Americans, this panel was apparently the accepted solution. Not trusting the creators to write the text, Superman’s carefully-worded speech was probably based upon a script provided by the OWI. No matter, it served its purpose and as news of the positive resolution leaked out, the various relocation camp newspapers reacted with mixtures of relief and gratitude.

TOPAZ TIMES, Aig. 17, 1943 & POSTON CHRONICLE, Aug. 18, 1943

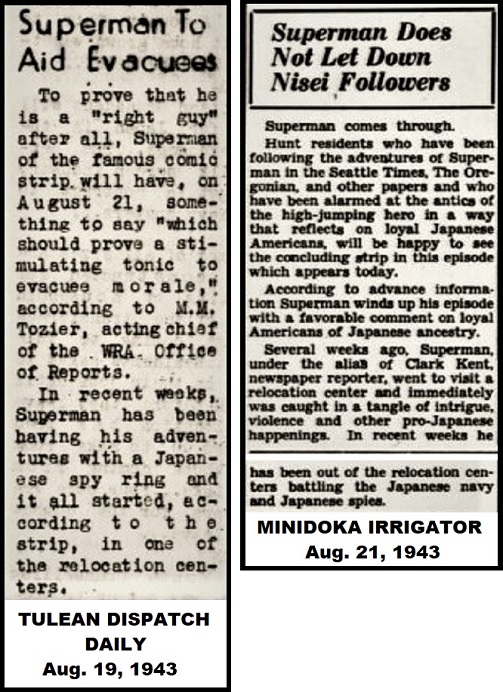

Most of the relocation camp papers accepted Superman’s positive finale as a morale boost for the internees and attempted to direct the focus on his battle against the Japanese navy.

DAILY TULEAN DISPATCH, Aug. 19, 1943 & MINDOKA IRRIGATOR, Aug. 21, 1943

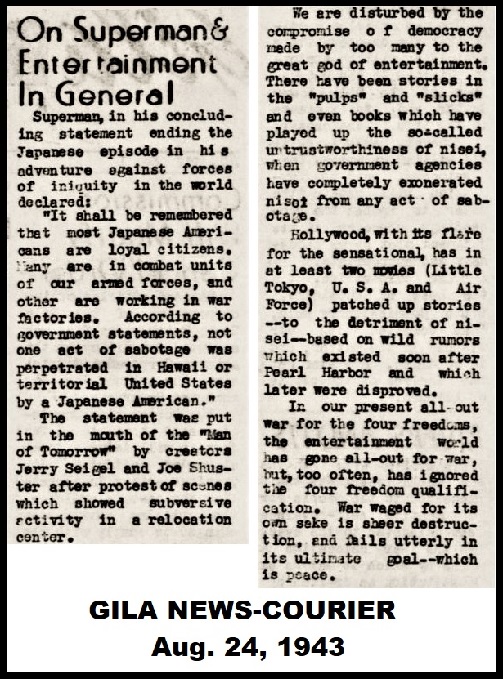

At least one camp newspaper, though, was more begrudging in its praise and took the entire media to task for its ongoing negative portrayal of Nikkei.

“The statement [by Superman] was put in the mouth of the ‘Man of Tomorrow’ by creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster after protest of scenes which showed subversive activity in a relocation center.”

“We are disturbed by the compromise of democracy made by too many to the great god of entertainment. There have been stories in the ‘pulps’ and ‘slicks’ and even books which have played up the so-called untrustworthiness of nisei [sic], when government agencies have completely exonerated nisei [sic] from any act of sabotage.”

“In our present all-out war for the four freedoms, the entertainment world has gone all-out for war, but, too often, has ignored the four freedom qualification.” [“On Superman & Entertainment in General,” GILA NEWS-COURIER, Aug. 24, 1943]

GILA NEWS-COURIER, Aug. 24, 1943

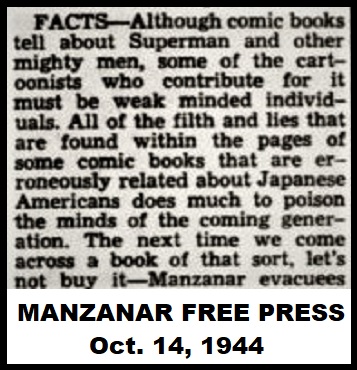

Eventually, the storm subsided and for the most part, Superman regained his reputation among the Japanese-American internees, as comic books reigned as the most popular reading material sold in the camp community stores.

MANZINAR FREE PRESS, Oct. 14, 1944

However, not everyone forgot, nor forgave. More than a year after the relocation camp story-line controversy had ended, a short editorial comment appeared in one of the camp papers that revealed little had changed and some bitterness remained.

“Although comic books tell about Superman and other mighty men, some of the cartoonists who contribute for it must be weak minded individuals. All of the filth and lies that are found within the pages of some comic books that are erroneously related about Japanese-American does much to poison the minds of the coming generation. The next time we come across a book of that sort, let’s not buy it.” [“Facts,” MANZINAR FREE PRESS, Oct. 14, 1944]

__________________________________

POSTSCRIPT

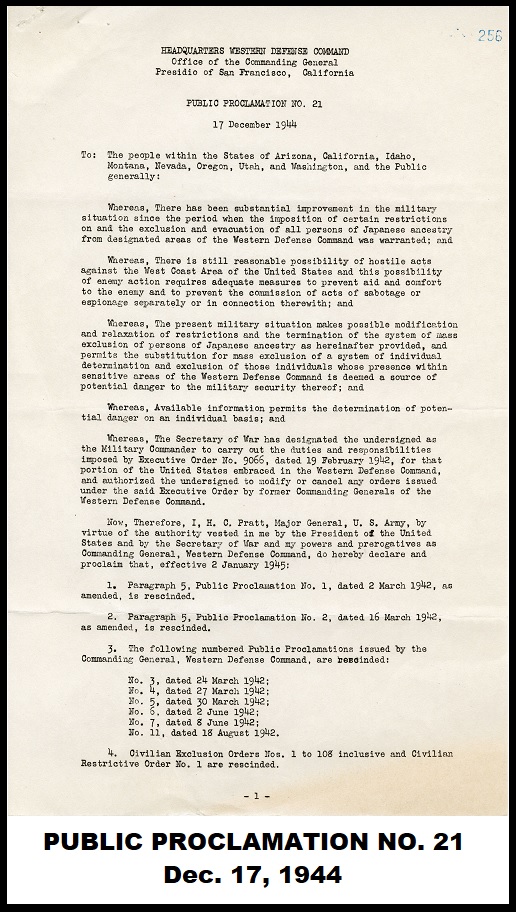

On December 17, 1944, Major General Henry C. Pratt issued Public Proclamation No. 21, declaring that, effective January 2, 1945, the internment of Japanese-Americans was ending and they could return to their homes.

PUBLIC PROCLAMATION NO. 21, Dec. 17, 1944

Eddie Sato, (1943)

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill giving each surviving internee $20,000 tax-free and an apology from the U.S. government.

One of those surviving Nisei was Eddie Sato, the Superman-loving cartoonist. After WWII, Sato came home to Seattle, married and became a noted graphic artist and a life-time proponent of redress for Japanese-Americans who had been sent to the relocation camps.

Late in life, Sato donated his personal sketchbook of drawings he had made while incarcerated at “Camp Harmony” to the University of Washington, where they are available for viewing online. Sato was 82 years old when he passed away in Chicago in 2005.