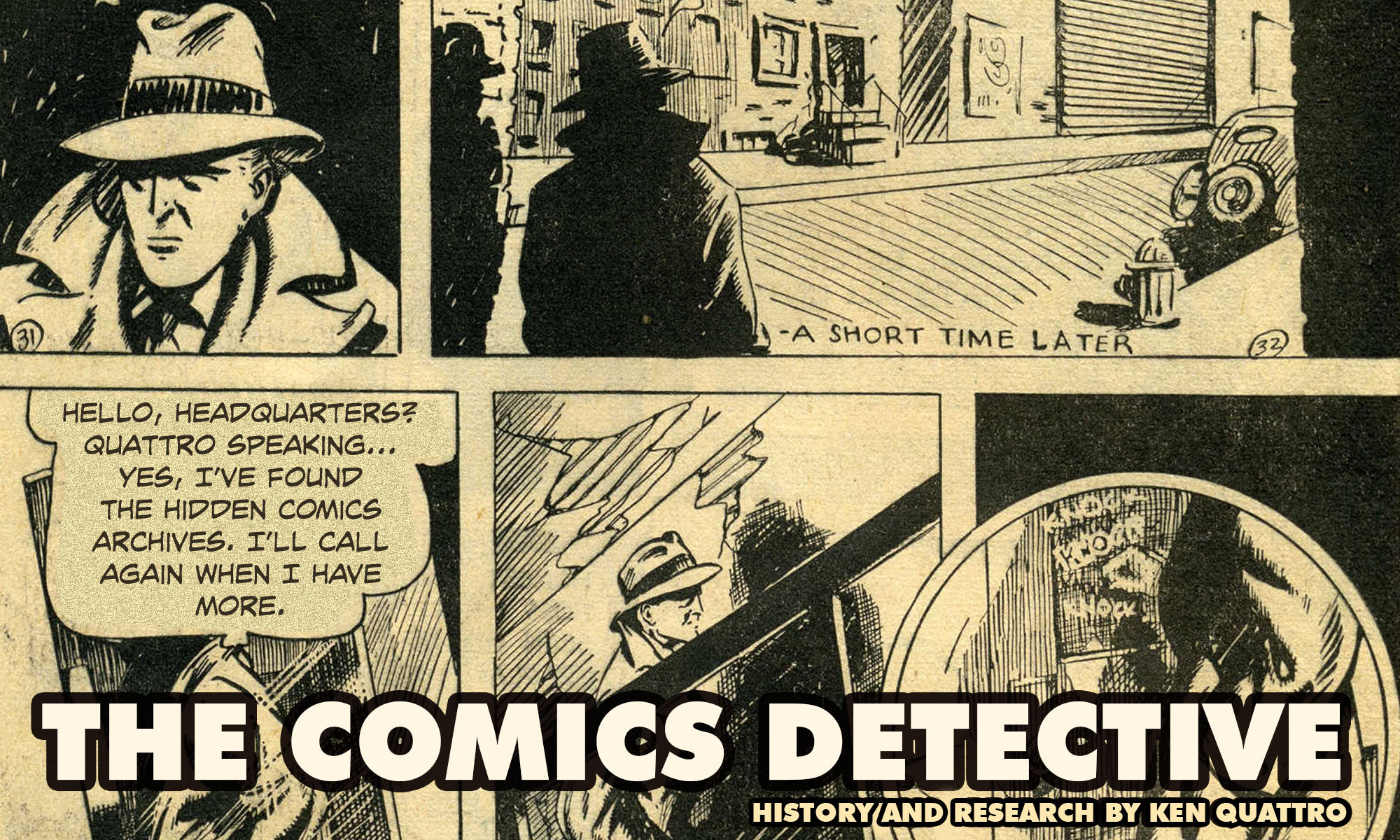

Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson

©2019 Ken Quattro

Not every story related to comics history involves super-heroes or the people who drew them. What follows is a story, a long story told in four parts, of a man, how he came to be and how he arrived at one point of his life. And like every story, this one has a beginning.

Though you won’t find it on any modern-day maps, the State of Franklin lay just west of the Appalachian Mountains, in the Cumberland River Valley, carved out of the northwest corner of North Carolina by its independent-minded settlers. These hardy frontiersmen and women had little in common with the rest of the state, which showed how little it cared about the region when it ceded it and the rest of what is now Tennessee to the United States Congress to help pay off its war debts in April 1784.

The residents of these western counties didn’t trust the New Englanders and northern elites who dominated the formation of the new United States and they feared the area would be sold to a foreign nation. Not only that, the cessation left them without a formal government, as North Carolina no longer controlled it. On August 23, 1784, a general convention was convened in the town of Jonesborough, a President was elected and a government began taking shape. At first named Frankland, the name was changed in 1785 to Franklin in honor of the great statesman/inventor Benjamin Franklin, with the hope of getting his endorsement of the region as the fourteenth state in the Union. He didn’t give it.

The next several years were fraught with confusion. The United States Congress refused to recognize Franklin as a state, so they declared their independence and existed for a time as a separate republic. Meanwhile, North Carolina withdrew its cessation of the area and reclaimed it as part of their state. Eventually, all this disarray and continual infighting among Franklinians led to its dissolution in 1788, and it once again became a part of North Carolina and when Tennessee was created, it formed the easternmost boundary of that state. The locals remained fiercely independent, a trait embodied by its most famous son, the legendary Davy Crockett, who was born not far from Jonesborough when it was still a part of Franklin.

Even more emblematic of this independent streak was the publication of the nation’s first abolitionist newspaper, THE EMPANCIPATOR, by Jonesborough’s Elihu Embree. The paper only lasted eight months, ending with Embree’s death, but it established the town’s reputation as an oasis of racial tolerance, with free Blacks residents coexisting along with the White population.

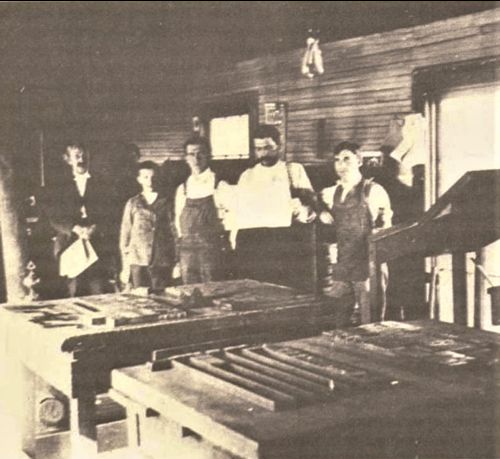

Decades later, on August 26, 1869, another newspaper was founded in Jonesborough titled, the JONESBOROUGH HERALD AND TRIBUNE. While the recent Civil War had settled the slavery issue, this new publication served as the voice of the progressive post-war Republican Party, and proudly displayed its guiding motto below its front-page masthead: “Honesty of Purpose, and Equal Rights to all Men, will secure happiness to the People.” [JONESBOROUGH HERALD AND TRIBUNE, Aug. 26, 1869.]

Office of the JONESBOROUGH HERALD AND TRIBUNE (c. 1869)

The owners and editors of the HERALD AND TRIBUNE were two of the town’s most prominent physicians, Dr. Mathew S. Mahoney and Dr. Christopher C. Wheeler. Little is known about Mahoney, other than he bought out Wheeler’s portion of the newspaper business in 1873. About Wheeler, though, much more is known.

Dr. Wheeler was born in Taunton, Massachusetts and had made his way to Jonesborough by way of his military service during the Civil War. He was a farmer in Palmyra, Illinois when the war broke out, newly married to a young Ohio-born school teacher named Sarah Adaline Ohmet. He joined the Union army with the creation of the 75th Illinois Infantry on September 2, 1862. Mustered in as a private, a cruel necessity born of war led to a battlefield promotion for the young soldier.

At the outbreak of hostilities, the Union army only had 114 surgeons within its ranks and 24 of them chose to join the Confederate states of their birth. Unlike today, doctors at that time frequently did not attend a medical school, instead, they would apprentice with a practicing physician to learn. The paucity of doctors pressed many untrained soldiers into service aiding the overwhelmed medical staff and it is likely this is how Wheeler earned his battlefield appointment.

Wheeler’s regiment had spent most of their time chasing Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Confederate troops through parts of Kentucky, Georgia and Tennessee. On May 23, 1864, Wheeler was promoted to Assistant Surgeon and assigned to the Union Army’s 8th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment Along with the job of surgeon came a change in rank. Like all surgeon’s serving in the Union army, he was assigned the rank of Major. Despite the fact that he no longer had to suffer the daily dangers of a foot soldier, Wheeler, as with all surgeons serving during the Civil War, would find it to be a brutal assignment.

“Battlefield surgery…was also at best archaic. Doctors often took over houses, churches, schools, even barns for hospitals. The field hospital was located near the front lines–sometimes only a mile behind the lines.” [“Civil War Medicine: An Overview of Medicine,” Ohio State University Dept. of History, https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/cwsurgeon/cwsurgeon/introduction, retrieved July 28, 2019.]

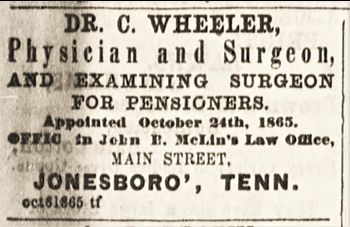

Wheeler surrendered his rank of Major when he was mustered out along with the rest of his regiment on September 11, 1865. Just over a month later, on October 27, 1865, Wheeler was appointed by the Federal government as an examining physician for the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was formed in 1863 to help the recently freed slaves acclimate to their new lives. One of the functions of the Bureau was providing health care to this desperately impoverished group of people who were often denied care by White doctors and hospitals. Dr. Wheeler was one of a handful of physicians entrusted to provide medical help to this under-served population.

THE UNION FLAG (May 4, 1866)

Even though he was a newcomer to the community, Dr. Wheeler quickly became one of Jonesborough’s leading citizens. As well as being a respected doctor and publisher, he was also vice-president of the local Literary Association, owned a drug store and a tannery and served on the Washington County Republican Committee leading up to the 1868 Presidential election.

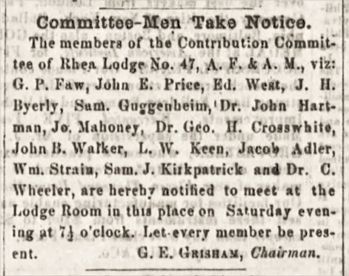

Wheeler also became a Mason, joining Rhea Lodge No. 47, the only Masonic lodge ever chartered by a future President of the United States, Andrew Jackson, who was the Grand Master of Tennessee at its founding in 1823. It was there that Wheeler likely crossed paths with William John Strain, another lodge member.

THE UNION FLAG (May 29, 1868)

Strain had far deeper Tennessee roots than Wheeler, with family settling in Washington County at least as far back as the late 1700s. While the Strain family’s history is sketchier than the Wheeler’s, it seemed to have similar humble beginnings. From census records it is known that William’s father was a trader and the son worked as a farm hand before becoming a merchant. He didn’t figure as prominently in Jonesborough’s history as did Dr. Wheeler, but for many years, Strain served as the town’s post master. And in 1876, he joined Wheeler as a county delegate to the Tennessee state Republican convention.

William and his wife Cynthia (neé Broyles) gave their only son the curious name of Lola Orlando Strain. Not much is known about the young man’s early years other than he married a local farmer’s daughter named Francis (aka “Fannie”) Byerly on September 12, 1878. He was 20 years-old and she only 19 at the time of their marriage. Late the next year, Fannie gave birth to a baby boy named Oakey. Three months later, she died.

The distraught father moved back in with his parents, who took over raising Oakey. But even under their care, the little boy couldn’t avoid the scourge of disease.

“Oakey Strain, only son of Mr. L. O. Strain, died at Limestone, Washington county, Saturday morning 24th October, 1885,” began his somber obituary, “Oakey was six years and eighteen days old. He was sick 8 days; died of diphtheria.” [“Obituary,” HERALD AND TRIBUNE, Jan. 7, 1886.]

There was an outbreak of diphtheria in the area at the time and it’s quite possible Dr. Wheeler treated some of the inflicted, perhaps even young Oakey. In an era when death came in many forms, even the family of a doctor wasn’t immune.

“At 10 o’clock last Tuesday morning, Mrs. Wheeler, wife of Dr. C. Wheeler, died after an illness of eleven days. Her death was quite sudden and its announcement here Tuesday morning was a shock to her many acquaintances.” [“Death of Mrs. Wheeler,” HERALD AND TRIBUNE, Nov. 26, 1885.]

The Wheelers had moved to Greeneville, some twenty-five miles from Jonesborough. Despite his personal tragedy, Dr. Wheeler continued to practice medicine, his skill known and often called upon in towns throughout eastern Tennessee. At some point, the middle-aged widower met Lucy Perkins, an art teacher living in Nashville.

Perkins had come to the United States from England in August 1885 and made her way to the bustling city that billed itself as the “Athens of the South” based upon its cultural sophistication and educational system. Lucy and her young relative Mabel, a vocal teacher, described in a newspaper article as “both ladies of culture,” secured employment at Ward’s Seminary soon after their arrival. It wasn’t long, though, until Lucy opened an art school of her own.

“Miss Lucy Perkins has returned from a summer vacation in Kentucky, and will receive her patrons and pupils at her residence.”

“The course will include free hand drawing from the flat and round, practical geometry and designing crayon work from the flat and round….Miss Perkins will this year offer medals for proficiency in each department of work, and will during winter deliver a course of lectures on the history of art and kindred subjects to her pupils.” [“Among the Artists,” THE TENNESSEAN, Sept. 16, 1886.]

A local newspaper took notice that “Miss L. Perkins an English Lady who has been teaching in Wards Seminary at Nashville is stopping for the summer at Dr. C. Wheelers [sic]. [THE COMET, July 12, 1888.]

Followed just over a month later by the announcement: “Last week Dr. C. Wheeler and Miss L. Perkins, of this place,, were married at Jonesboro.” [THE COMET, Aug. 30, 1888.]

Any joy surrounding Dr. Wheeler’s marriage was swiftly overshadowed by yet another tragedy.

“Died this evening of paralysis of the brain, Gracie, the six-year-old daughter of Dr. C. Wheeler. She had been afflicted with epilepsy for several years.” [ THE COMET, Sept. 27, 1888.]

Dr. Wheeler and his first wife Sarah had five children—Charles, Eugene, Nettie, Edith and the deceased Gracie. Eugene became a physician, just like his father, and moved to Denver, Colorado. The rest of the Wheeler children stayed close by their father in Tennessee. The previous year, his oldest daughter, Nettie, married Lola Strain, the post master’s son, in Jonesborough on March 2, 1887. It wasn’t long after that they began a family of their own.

By May 1890, Lola was named as a stockholder and secretary treasurer of the newly opened Watagua Lumber Company in nearby Johnson City. It wasn’t long before the company ran into money problems from their inability to collect on debts owed. In August 1891, it was forced to close. The impact of its closing apparently affected Strain’s personal finances, as over the next couple of years, he was suing Watauga Lumber and was being sued by others himself.

Making matters worse for the Strains was yet another unexpected death. On May 14, 1893, Dr. Christopher Wheeler died suddenly. The shock of his demise was met not only with grief by family members, but also suspicion.

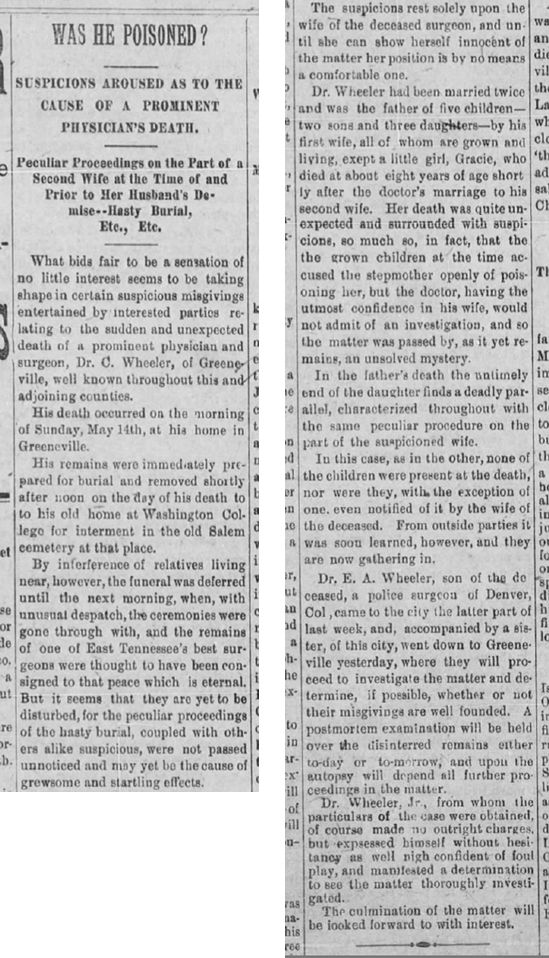

THE COMET (June 1, 1893)

“[Dr. Wheeler’s] remains were immediately prepared for burial and removed shortly after noon on the day of his death to his old home at Washington College for interment in the old Salem cemetery at that place.”

“By interference of relatives living near, however, the funeral was deferred until the next morning, when, with unusual dispatch, the ceremonies were gone through with, and the remains of one of East Tennessee’s best surgeons were thought to have been consigned to that peace which is eternal. But it seems that they are yet to be disturbed, for the peculiar proceedings of the hasty burial, coupled with others alike suspicious, were not passed unnoticed and may yet be the cause of grewsome [sic] and startling effects.”

“The suspicions rest solely upon the wife of the deceased surgeon, and until she can show herself innocent of the matter her position is by no means a comfortable one.” [“Was He Poisoned?” THE COMET, June 1, 1893.]

The stunning accusation that Dr. Wheeler had been poisoned by his wife Lucy was front page news. The article went into detail concerning the allegation and revealed some lingering doubts from years before.

“Dr. Wheeler had been married twice and was the father of five children—two sons and three daughters—by his first wife, all of whom are grown and living except a little girl, Gracie, who died at about eight years of age shortly after the doctor’s marriage to his second wife. Her death was quite unexpected and surrounded with suspicions, so much so, in fact, that the grown children at the time accused the stepmother openly of poisoning her, but the doctor, having the utmost confidence in his wife, would not admit of an investigation, and so the matter passed by, as it yet remains an unsolved mystery.” [Ibid.]

Curiously, the article neglected to mention that Gracie had suffered from epilepsy and her death was determined to due to that disease. The resentment of the doctor’s grown children to their stepmother evidently was long lived and the article didn’t hesitate to report their accusations without equivocation.

“In the father’s death, the untimely end of the daughter finds a deadly parallel, characterized throughout with the same peculiar procedure on the part of the suspicioned [sic] wife.”

“In this case, as in the other, none of the children were present at the death, nor were they, with the exception of one, even notified of it by the wife of the deceased.” [Ibid.]

Dr. Eugene Wheeler returned from Denver and joined his sister Nettie in investigating the circumstances of their father’s death. At their bidding, his body was disinterred and a postmortem examination was conducted. The results were released a week later.

“A post-mortem examination was held yesterday over the exhumed remains and both the heart and stomache [sic] thoroughly examined by competent physicians. They could find no trace of poison or any evidence of violence whatever, but declare the cause of death to have been falty [sic] generation of the heart, that organ being swollen to at least twice its natural size.” [“Was Not Poisoned,” THE COMET, June 8, 1893.]

The COMET, which had previously presented the Wheeler family’s suspicions without question, reported the autopsy’s outcome with similar deference.

“All parties express themselves as satisfied if not exultant over the decision, the relatives, by whom the investigation was instituted, being glad to know that no further procedure is necessary. They were naturally desirous of putting their suspicious misgivings to a test and were perfectly justifiable in doing so, as long as no direct charges were made. But the innocence of the suspicioned [sic] step-mother has asserted itself; the curiosities of those who have watched the case are satisfied, and it is altogether well that its culmination was not as it first promised to be.” [Ibid.]

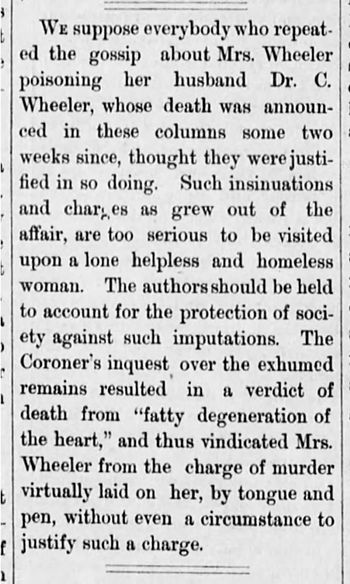

The rival Jonesborough HERALD AND TRIBUNE was far less circumspect in assigning blame to Lucy Wheeler’s accusers.

JONESBOROUGH HERALD AND TRIBUNE (June 8, 1893)

“We suppose everybody who repeated the gossip about Mrs. Wheeler poisoning her husband Dr. C. Wheeler, whose death was announced in these columns some two weeks since, thought they were justified in so doing. Such insinuations and charges as grew out of the affair, are too serious to be visited upon a lone helpless and homeless woman. The authors should be held to account for the protection of society against such imputations. The Coroner’s inquest over the exhumed remains resulted in a verdict of death from ‘fatty degeneration of the heart,’ and thus vindicated Mrs. Wheeler from the charge of murder virtually laid upon her, by tongue and pen, without even a circumstance to justify such a charge.” [HERALD AND TRIBUNE, June 8, 1893.]

In any event, the whole sordid episode laid bare the bitter relations between the Wheeler children and Lucy Wheeler, a situation no doubt exacerbated when, as his widow, applied for his Civil War veteran’s pension just days after his death. Her haste in applying so quickly may in part be explained by the fact that Dr. Wheeler left a lot of debt behind when he died and not enough money to pay all of his debtors. Not the least of these was the State of Tennessee, to which he owed on delinquent taxes.

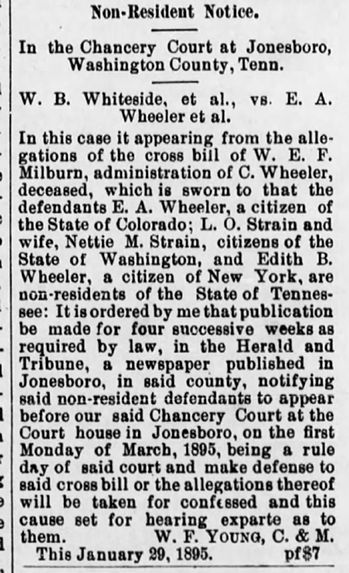

As his estate’s administrator dealt with the pile of unpaid bills and attempted to reach settlements with the various debtors, his heirs, his children, were also drawn in. In December 1894, local businessman W. B. Whiteside sued Dr. Eugene Wheeler, his sister Edith and the Strains for undisclosed amounts likely related to their father’s estate.

Complicating the matter for the Strains was that they had recently separated. It had been a hard year for them. They had begun the year with the birth of their youngest son, Christopher, on January 3rd, and then suffered the trauma of the death of their oldest child Caroline on November 26th. Along with their own financial difficulties, it was all too much and they separated soon after. Lola Strain moved to Oregon, while his wife Nettie went north to New York.

Nettie and her children must not have stayed in New York (probably living with her sister Edith, who had become a nurse in Buffalo) very long, as the legal notice of the Whiteside lawsuit against her and her family, was altered in February 1895 to show that she now had relocated to Oregon as well (although the legal notice curiously, and probably mistakenly, claimed it was “Washington” state).

JONESBOROUGH HERALD AND TRIBUNE (Feb. 27, 1895)

Nettie settled into life in Oregon, finding a job in Portland as an office stenographer. She hadn’t entirely left her old problems behind, as a legal notice appearing in THE COMET on December 19, 1895, indicated that a bank in New York had named her in yet another lawsuit.

Still, she had determined to make a new start, to the point of creating new identities for her and her two surviving children. Nettie M. Strain began going by the name “Antoinette Wheeler Strahan,” and changed the boys’ names to match. According to the 1900 census, she also began claiming that she and the children had been born in New York, erasing evidence of their previous lives in Tennessee. It was a rebirth for Antoinette, six year-old Christopher and his ten year-old brother, Malcolm.