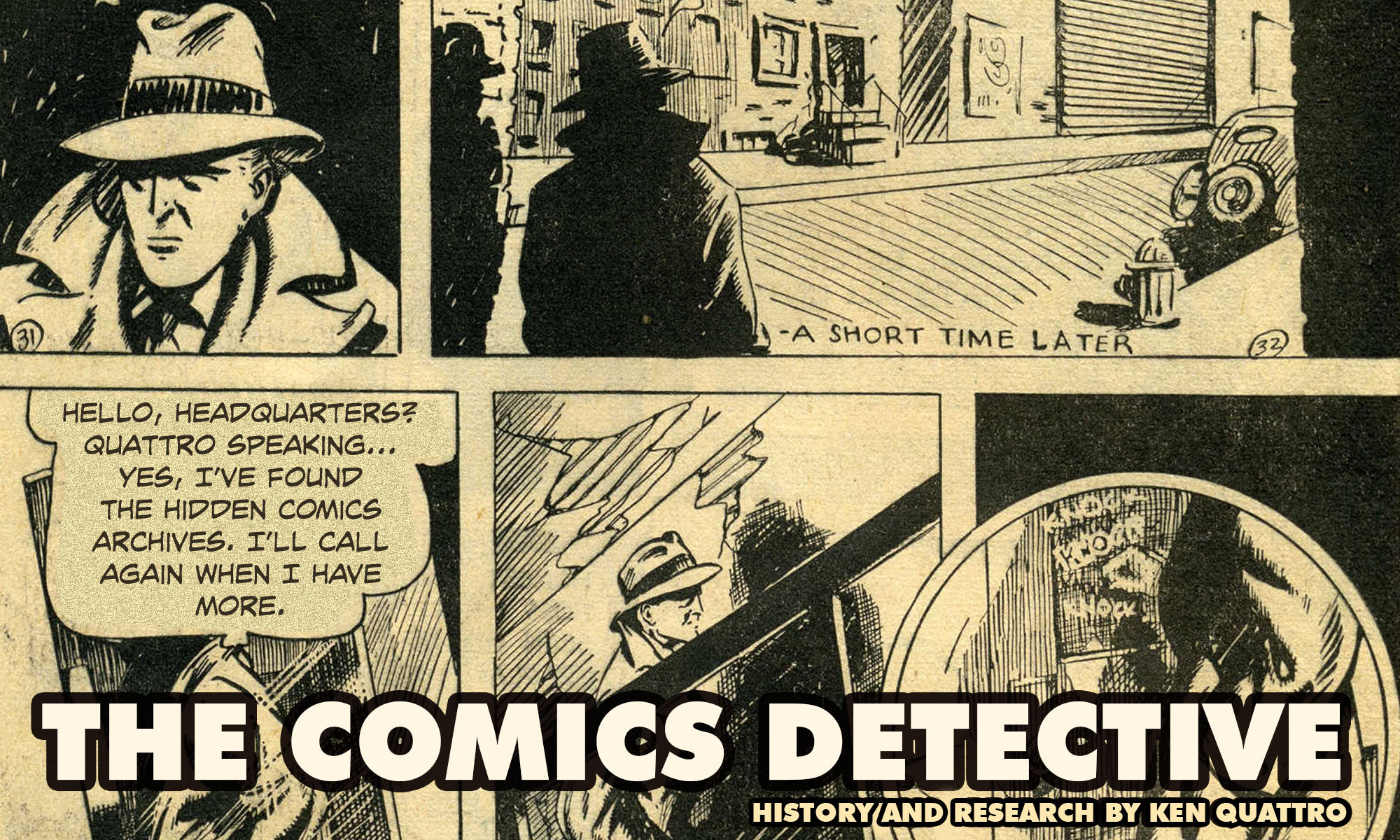

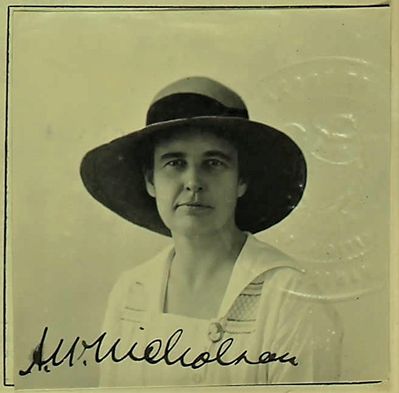

Antoinette Wheeler-Nicholson (1918)

©2019 Ken Quattro

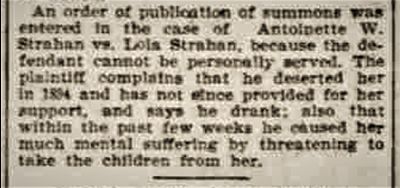

The dawn of a new century brought with it the chance of a new life for Antoinette Strahan and her children. To make a complete break with her past, Antoinette (aka Nettie) made a formal declaration of her separation from her husband, Lola.

MORNING OREGONIAN (June 19, 1900)

“As order of publication of summons was entered in the case of Antoinette W. Strahan vs. Lola Strahan, because the defendant cannot be personally served. The plaintiff complains that he deserted her in 1894 and has not since provided for her support, and says he drank; also that within the past few weeks he caused her such mental suffering by threatening to take the children from her.” [“Divorce Suits,” MORNING OREGONIAN, June 19, 1900.]

The difficulty in serving Lola with divorce papers likely came from the fact that he was living in the sparsely populated town of Butteville, Oregon, more than 20 miles south of Portland. Going by the name of “Lew Strain,” Lola was working as a farmhand on the hops farm owned by Harry J. Pulfer.

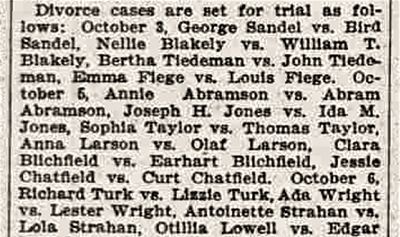

In any case, the October 2nd edition of the OREGONIAN announced that the divorce case of Antoinette Strahan vs. Lola Strahan was set for trial four days later. Since children were involved in the matter, it can be assumed that the divorce was finalized some months after. As far as can be determined, Lola Strain exited the life of his children at this point and passed away (under the first name of “Louis”) sometime in 1905.

MORNING OREGONIAN (Oct. 2, 1900)

Antoinette blossomed in the wake of her divorce. An article appeared in July 1901, crediting her for her work on a new woman’s magazine.

“The Club Journal published in Portland by Mrs. Sarah A. Evans and Antoinette Wheeler Strahan increases in vigor and usefulness as it grows in age. The third number shows a deepening tone of earnestness toward the problems that are now engaging the attention of womanhood.” [“Club Journal for July,” MORNING OREGONIAN, July 29, 1901.]

Both Antoinette and the CLUB JOURNAL were in for more accolades, which were noted in an article later that year concerning a meeting of the Portland Woman’s Club.

“The resolution was one in commendation of the Club Journal, edited by Antoinette Wheeler Strahan, and ran as follows: Resolved, That the executive board of the Woman’s Club, of Portland, cordially commends the management of the Club Journal, and recognizes it as an able exponent of the Woman’s Club movement throughout the state.” [“Tribute to Gen. Stevens,” MORNING OREGONIAN, Dec. 28, 1901.]

Antoinette’s profile in Portland grew, as she became a charter member of the Lewis and Clark Civic Improvement Association, an organization intent upon beautifying Portland, in February 1902. And on June 15, 1902, Antoinette W. Strahan and Thomas J. B. Nicholson applied for a marriage license.

Antoinette’s betrothed, Thomas John Bell Nicholson, was an English stockbroker who had migrated to the United States back in 1889. His father George was a merchant sea captain back in the port city of Kingston upon Hull in East Yorkshire, who became a widower when Thomas was six years-old.

Thomas had been living in Portland since the early 1890s, at least, most of that time as an employee of Pacific Coast Elevator Company in various accounting and secretarial positions. Yet, he also came into the marriage to Antoinette with some personal baggage.

On the 1910 Federal Census, Antoinette honestly indicated that she had been married twice. Thomas claimed that he had married just once. However, on the 1930 census, he clearly stated that his first marriage came when he was 25 years-old, which would have been in 1888, the year before he came to America. If he was divorced, why didn’t he just state that, as Antoinette had previously? Or had he abandoned a wife in England?

His other issue was more immediate. In late 1902, Thomas was sued by a former fiancée who claimed that he jilted her and broken their engagement.

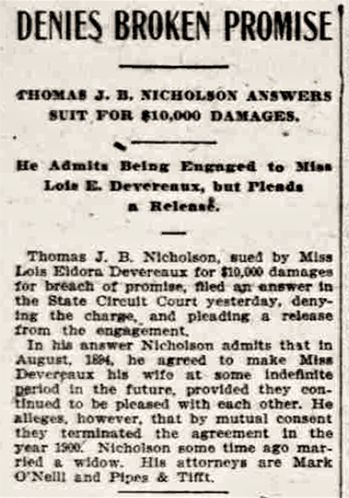

SUNDAY OREGONIAN (Nov. 16, 1902)

“Thomas J. B. Nicholson,sued by Miss Lois Eldora Devereaux for $10,000 damages for breach of promise, filed an answer in the State Circuit Court yesterday, denying the charge, and pleading a release from the engagement.”

“In his answer Nicholson admits that in August, 1894, he agreed to make Miss Devereaux his wife at some indefinite period in the future, provided they continued to be pleased with each other. He alleges, however, that by mutual consent they terminated the agreement in the year 1900. Nicholson some time ago married a widow.” [“Denies Broken Promise,” SUNDAY OREGONIAN, Nov. 16, 1902.]

In point of fact, Nicholson’s current wife Antoinette wasn’t a widow when they married, as her ex-husband Lola was still alive at the time. It was a claim that Antoinette made at other times as well. Presumably, it was better to be a widow than a divorcée.

When the case came to trial in January 1903, Devereaux’s attorney introduced a stack of love letters written to her by Thomas and he suffered the humiliation of having them read aloud to the court.

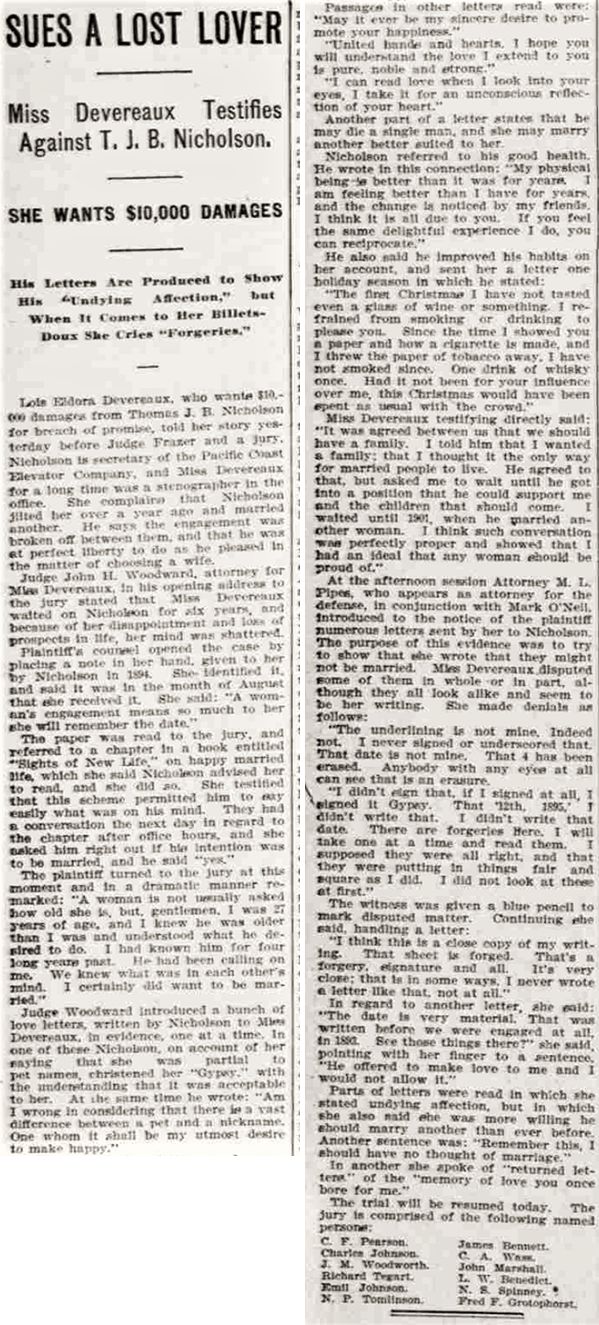

MORNING OREGONIAN (Jan. 27, 1903)

“Plaintiff’s counsel opened the case by placing a note in her hand, given to her by Nicholson in 1894. She identified it, and said it was in the month of August that she received it. She said: ‘A woman’s engagement means so much to her she will remember the date.’”

“Judge Woodward [Devereaux’s attorney] introduced a bunch of love letters, written by Nicholson to Miss Devereaux, in evidence, one at a time. In one of these Nicholson, on account of her saying that she was partial to pet names, christened her ‘Gypsy,’ with the understanding that it as acceptable to her. At the same time he wrote: ‘Am I wrong in considering that there is a vast difference between a pet and a nickname. One whom it shall be my utmost desire to make happy.’” [“Sues a Lost Lover,” MORNING OREGONIAN, Jan. 27, 1903.]

Devereaux’s testimony dragged on into the afternoon, with similarly cringeworthy revelations being read before the court. The trial was set to continue the next day when it came to a sudden halt.

“Judge Woodward said that certain unlooked-for developments having arisen since the trial was begun, he proposed to pause and ask for a nonsuit for the purpose of leaving the case unprejudiced until he could institute a thorough investigation of certain matters. Counsel referred to certain letters of Miss Devereaux which had been introduced, some of which and parts of others she denounced as forgeries.”

The presiding judge agreed to Devereaux’s request to suspend the case and returned the letters to her. Her attorney added “that unexpected publicity to such an extent that it proved embarrassing had affected the young woman. A great deal of publicity had been given to the matter, which was not pleasant. This statement alluded to portions of letters published and evidence in the case.” [“Publicity was Painful,” MORNING OREGONIAN, Jan. 28, 1903.]

It can be assumed that Nicholson felt much the same way.

This embarrassing episode past, Antoinette Wheeler-Nicholson, who affixed her own last name to her married one with a hyphen, went about her burgeoning journalistic career, often contributing to the OREGONIAN, the newspaper that had covered her husband’s trial so breathlessly.

Most of Antoinette’s writings dealt with matters of child rearing and issues concerning women, probably as an outgrowth of the reputation she had acquired through the CLUB JOURNAL.

“The majority of women who apply for divorces do so after enduring conditions that no man would endure for a moment; as a last resort in a desperate fight for their children and their own self-respect.” [“The Unwelcome Gift of Life,” MORNING REGISTER, Jan. 1, 1906.]

In this particular example, Antoinette wrote about the social stigma attached to women who divorced, as opposed to the women who were lauded when they stayed with drunken husbands because society demanded it. Undoubtedly, the personal experience of her marriage to Lola Strain provided the force behind her words.

“Public opinion should be strongest against the continuation of the marriage relation under such circumstances. This sort of woman should be condemned for her deplorable weakness, her lack of self respect and utter disregard for her children’s welfare. No woman should be allowed to live with a drunken dissolute husband from a mistaken sense of duty or for fear of what the world will say is she leaves him. She should be taught that her first duty is toward the children born and unborn for whom she is responsible, and to her own self respect.” [Ibid.]

It was another trauma that informed a letter that she penned to one of the leading authors of the day and prompted his reply to her in turn.

“Very many thanks for your letter with the cutting, and for what you say about my work. I’d like to think a little of it was true—in spots—some time. But I’m very pleased. I’m sorry you don’t approve of my remark about women but remember I only said that ‘Blind Nature had made her for one end.’ I never said what the woman said what the woman said about being made for that one end, and of course my own opinion is that it’s the highest and holiest of all. It seems to me that a woman who makes one man—even though he mightn’t be quite a success—does more than a million who say how man should be taught etc.”

“Perhaps that’s because I wasn’t born in a white man’s country, and the idea of a woman going out to work for her living among men doesn’t ever please me. She’s too good for that job, even when she says she isn’t.”

“I am honoured by all you have told me concerning your life; and it seems to me to prove once more that women have more courage in life than men.”

“Very sincerely yours, Rudyard Kipling” [Rudyard Kipling letter to Mrs. T.J.B. Nicholson, July 18, 1907.]

Kipling’s reply to Antoinette, at once both patronizing and gracious, came in response to her letter and enclosed newspaper clipping of an article she wrote for the OREGON DAILY JOURNAL on June 21, 1907. In it, she praised Kipling’s writings and defended him against a negative review another had written for the SUNDAY OREGONIAN back on May 12th of the same year. While she emphatically approved of Kipling’s authorship on a variety of stories and poems, she mildly rebuked him his stance “for the ‘mothers of man’ who willingly bear and gladly rear their broods he reserves the tender treatment denied the parasitic women and effeminate, parasitic men.” [“The Sons of Mary and Martha and Some Other Things,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, June 21, 1907.]

Knowing of her past heartbreak, Antoinette’s words take on a painful poignancy when she credits Kipling for being “born with the genius which made it possible for Kipling at 22 to divine ‘the hell of self-questioning provided for those who have lost a child and believe that with a little—just a little—more care it might have been saved.’” [Ibid.]

This correspondence with Kipling was likely the first contact Antoinette ever had with the author. His life and travels have been painstakingly recorded and his only visit to Portland up to 1907, came in June 1889, a trip he mentions fondly in another portion of his reply to Antoinette.

Meanwhile, the Wheeler-Nicholson boys were enjoying life on the horse farms the family had outside Portland in Oswego and later, Trout Lake, Washington. They had bonded with their stepfather Thomas, with Malcolm even joining the local Riverside Driving Club together in February 1906. The club advocated for road improvements in Portland to increase the pleasure of driving.

Malcolm was attending the A. C. Newell Riverside Academy, a boys prep school known for its picturesque views of Mt. Hood and that “the school gives to the scholar the benefit of a military training and the neat uniforms of the cadets are well known in all the circles of polite society of Portland.” [“Portland’s Academies and Colleges,” OREGON SUNDAY JOURNAL, Dec. 25, 1904.]

Antoinette, who had become a fixture within Portland’s “polite society,” evidently made sure her sons would be as well. Newell Riverside, whose “pupils rank from the youngest boy of school age to the youth completing his academic course or preparing for college,” promised each student “individual attention.” [Ibid.]

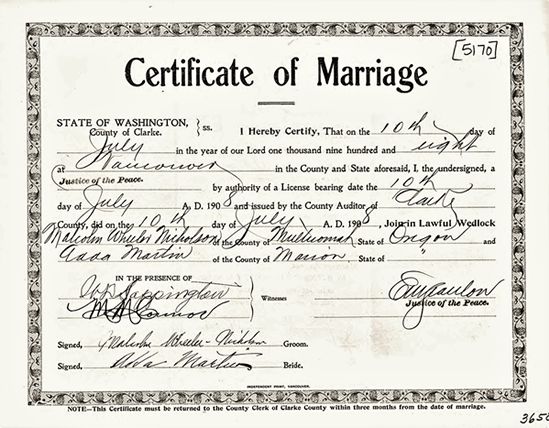

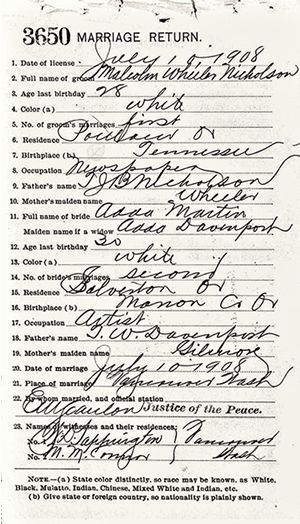

Before Malcolm would move on, though, his life took another turn. On July 10, 1908, Malcolm married Adda Davenport-Martin across the state line in Vancouver, Washington.

Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson & Adda Davenport-Martin marriage license (July 10, 1908)

Davenport-Martin, was, according to their marriage documents, an artist, specifically, a sculptor of note. She was also the possessor of “an unusually strong, rich voice, which, altogether with cultivation, entitles her to a position in the front ranks of Oregon’s best singers.” [“Salem Women,” CAPITAL JOURNAL, Nov. 23, 1895.]

Originally from Silverton, Oregon, Adda had become not just one of the most sought after singers in the capital city of Salem, but deemed praiseworthy for her other attributes.

“Miss Davenport possesses an exceptional physique,” noted the unnamed author of the article, “and unexcelled health, having always adhered to a hygienic style of dress.” [Ibid]

So, too, the reporter claimed her to be “an elocutionist of rare ability…a model housekeeper, and as a seamstress would shame many a professional dressmaker.” [Ibid.]

Adda had noteworthy family as well. She was not only the daughter of the secretary of the state Land Office, but also the sister of famed cartoonist Homer Davenport, one of America’s leading political cartoonists of the day.

With so much going for her, it is no wonder that Adda soon became engaged and on July 15, 1896, married Carey F. Martin. Martin, coincidentally, happened to be the editor of the CAPITAL JOURNAL which ran the glowing biography of his bride.

It was not to last. Carey Martin filed for divorce from Adda in May 1902, claiming desertion. It is not known how she met Malcolm, but one thing is clear: she didn’t know how old he was at the time of their marriage.

Both their marriage return and the Multnomah County Register of Marriage Statistics clearly show that 18 years-old Malcolm claimed he was 28 years-old, putting him only two years younger than Adda.

Wheeler-Nicholson & Davenport-Martin marriage return (July 10, 1908)

The marriage didn’t last long. By the time of the 1910 Federal Census Adda had moved back in with her parents and listed herself as being divorced. Malcolm, too, was living with his parents, but he simply listed himself as “single.” It’s possible, and quite likely, that the marriage was annulled when Adda found out the true age of her husband.

One bit of truth contained in the marriage documents, though, is that Malcolm referred to his occupation as “newspaper.” His first real job was with the PORTLAND TELEGRAM and based upon the date on the license, he must have been employed over the summer break from school.

This inconvenient marriage didn’t stop Malcolm from getting into the small, but well-regarded, St. John’s military school in Manlius, New York. It took a little help, though, from his mother for him to be admitted.

“Because of a slight defect in his eyesight his admission to the military school was challenged., but through the efforts of Senators Bourne and Chamberlain of Oregon he was passed and recommended highly by the examining board.” [“Honor Trout Lake Boy,” SPOKESMAN REVIEW, Dec. 17, 1911.]

SPOKANE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW (Dec. 17, 1911)

Antoinette’s political connections spanned both parties, as Sen Jonathan Bourne, a Republican and Sen. George E. Chamberlain, Democrat, both responded to her plea to write letters encouraging Malcolm’s admission to St. John’s. He proved them right, as Malcolm reportedly excelled in virtually every aspect of the school’s curriculum. Among his achievements was the awarding of the Iron Cross of the Legion of Honor to him for his rescue of three classmates from drowning in 1909. He graduated from St. John’s on June 15, 1910.

It was Malcolm’s eyesight that once again proved to be an obstacle when he went to join the U.S. Army. And once again, it took the intervention of a Senator to get him and two other prospective soldiers, into the service.

SUNDAY OREGONIAN (March 3, 1912)

“Senator Chamberlain interviewed each of the young men; found them bright, intelligent, and fine appearing young fellows, and straightaway went to the War Department to protest against their rejection on what he considered technical grounds. It required a good deal of leg work and a greater amount of persuasion on his part to bring the officials to his way of thinking…”

“…when he showed that the one man [Malcolm] had injured his sight by overstudy in preparing for the Army examination, and when he insisted that passage of a final examination was indication enough as to a man’s qualification for appointment to the service, he finally won.” [“Commissions Are Won,” SUNDAY OREGONIAN, March 3, 1912.]

The claim that “overstudy” caused Malcolm’s eyesight problem was demonstrably untrue, as the same problem existed when he applied to St. John’s, but it helped to have a United States Senator on his side, and so Malcolm was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Cavalry on Oct. 6, 1911.