©2020 Ken Quattro

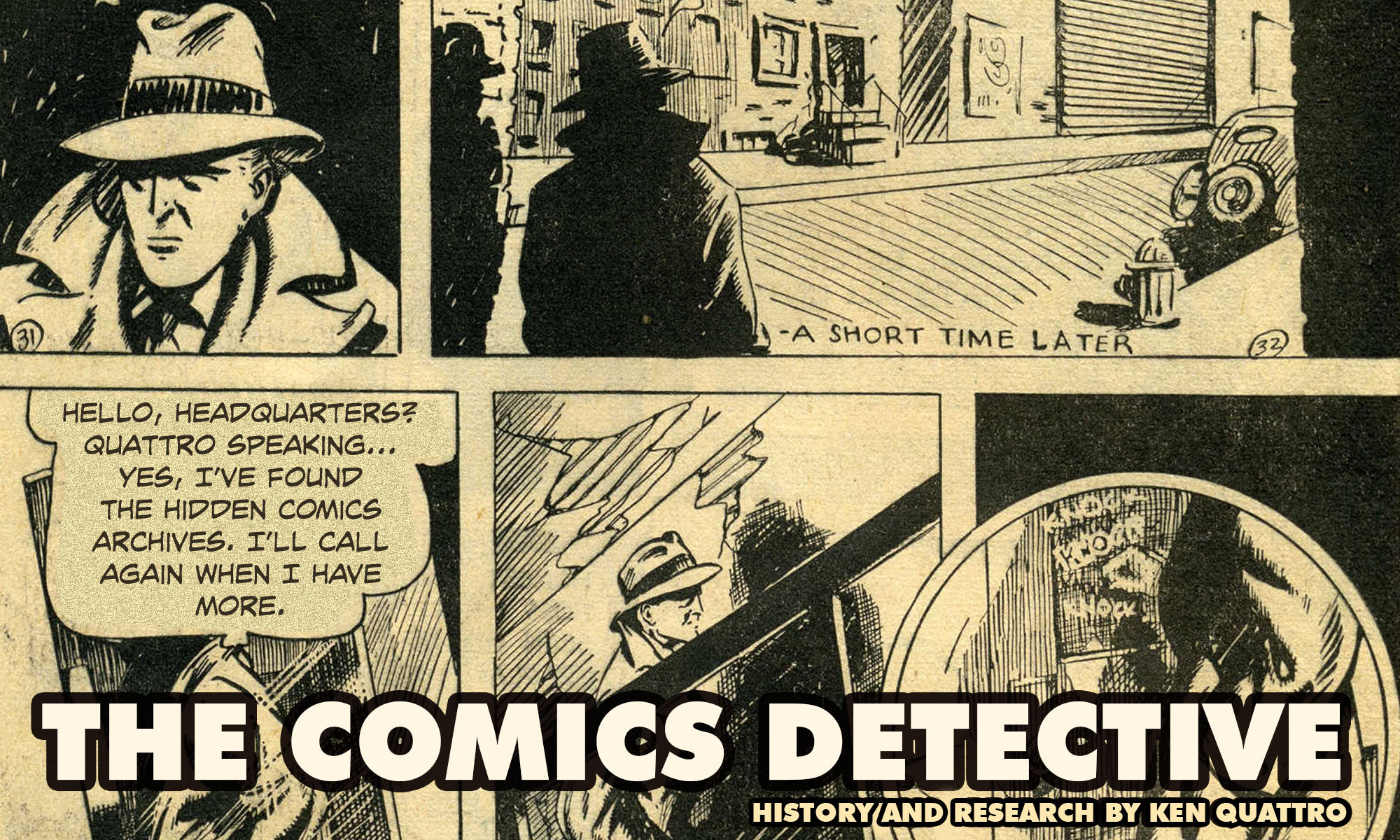

PROLOGUE:

Comic book history has mostly been viewed from the perspective of the male reader. As a consequence, male comic fans, (and I include myself) have a blind spot. If a comic or a genre falls outside our realm of interest, we discount it. Romance comics rank at the top of that ignoble list.

The artists who drew those ignored works generally get the same cold shoulder. A few have achieved fans beyond the romance genre–Matt Baker, of course, but it was his depiction of beautiful women that brought him fame. Alex Toth, John Romita and Jay Scott Pike to some extent, all toiled in the romance comics, but each managed to escape the anonymity by drawing fan faves in male-approved venues.

But one of the most talented romance artists of all still escapes the appreciation of most male fans.

This is the story of Tony Abruzzo.

________________________________________________

The incoming ship’s emptied their human cargo onto Ellis Island; immigrants seeking something other than what they had known. Few were moneyed, most were poor. Everyone looking for opportunity they hadn’t had before.

Europe provided most of this “wretched refuse,” from every country and region city and hamlet. The Irish then the Germans took their turns filling the boats, and in the decades straddling 1900, it was mainly Italians. Around four million total, more than half in the first ten years of the new century.

When the 1,600 souls crammed onto the S. S. Belgravia were disgorged on American soil June 24, 1892, among them were two-year old Antonio Abruzzo Jr. and his family. They had emigrated from Sicily and quickly mingled into the teeming immigrant masses congregated in Brooklyn, New York.

In those days, names and ages changed to fit the need and often without legal approval. Antonio’s name was Anglicized to Anthony and eventually, he met a young woman named Amelia Kehnle.

Amelia also went by the first name of Mildred and sometimes, Millie. She lived only two blocks from Anthony and had lost both her mother and father by the time she was age 13. Amelia was still quite young when Anthony got her pregnant without the formality of being married. Their baby, a girl, died at birth without a name on February 7, 1914, when Amelia was only 16 years old. By the time of the 1915 New York census, they were said to be married and she was claiming to be 19 at the time.

Soon, though, Amelia (now going by the name Mildred), did marry Anthony and she was pregnant once again. This time the baby lived. On June 21, 1916, she gave birth to a boy they named Anthony Joseph Abruzzo.

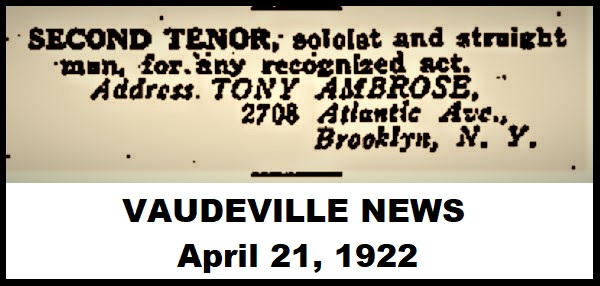

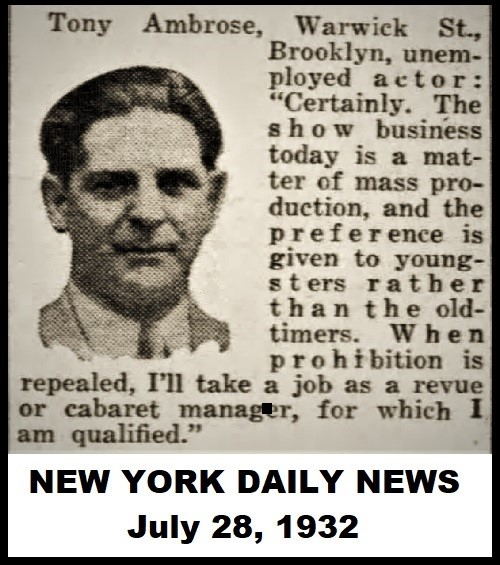

Anthony, the father, had chosen a profession that did not provide a steady income. He was an professional entertainer–an actor, a singer and a comedian. As consequence of their mean circumstance, the Abruzzos lived with extended family in a cramped Brooklyn tenement on Atlantic Avenue. Still, Anthony, using the less-Italian sounding name of Tony Ambrose, pursued his stage career. He even ran ads providing his skills as, “second tenor, soloist and straight man for any recognized act.” [Free Want-Ad Department, VAUDEVILLE NEWS, April 21, 1922.]

VAUDEVILLE NEWS, April 21, 1922

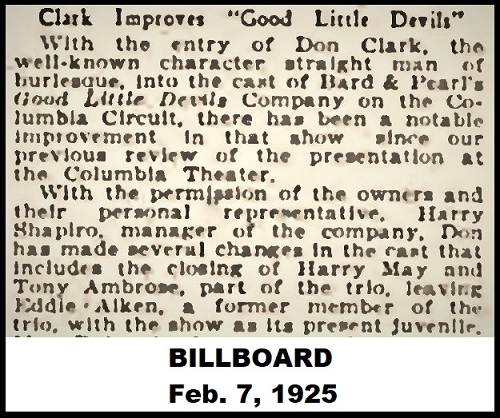

Even after Anthony became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1917, his stage career provided an inconsistent pay day and he frequently forced toured the burlesque circuit that took him away from New York and to points all over America.

BILLBOARD, Feb. 7, 1925

Meanwhile, Mildred and young Anthony were at home in tight quarters with their in-laws. A difficult situation in the best of marriages, more so in one with one partner often absent. Eventually, unsurprisingly, the marriage broke down. Anthony and Mildred divorced, with their son staying with his mother.

Mildred and Anthony moved back in with her family on Vermont Street in Brooklyn. She took regained her last name of Kehnle, while Anthony kept the name Abruzzo. At some point she met Louis Priore, an insurance salesman four years younger than her, and they married on November 27, 1928, and moved into an apartment on 103rd Avenue in Ozone Park, Queens.

Her ex-husband Anthony remarried as well. In 1929, he went on a vaudeville tour in Australia. There, he met Evelyn Hayes, a very young actress who moved to the U.S. that year and they married on June 27, 1930, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Evelyn was only 18 at the time, Anthony was 40.

His career was also on the downswing. Like many others during the Great Depression, Anthony found himself unemployed. There was some obvious bitterness in his answer when he was approached in Times Square one day, and asked by the “Inquiring Photographer” from the DAILY NEWS if he would accept any other job than that of an actor.

“Certainly. The show business today is a matter of mass production, and the preference is given to the youngsters rather than the old-timers. When prohibition is repealed, I’ll take a job as a revue or cabaret manager, for which I am qualified.” [“The Inquiring Photographer,” NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, July 28, 1932.]

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, July 28, 1932

Mildred fared better. After her divorce, she and son Anthony moved in with her older brother William and his family on 351 Vermont Street in Brooklyn. When she married Louis Priore, the three of them moved into a new, two-story, two-family home at 102-03 103rd Avenue in Ozone Park, Queens. It was a burgeoning suburb at the time, with plenty of homes and schools being built to accommodate the influx of Italian immigrants moving into the neighborhood.

Louis Priore and Mildred Kehnle Priore (1942)

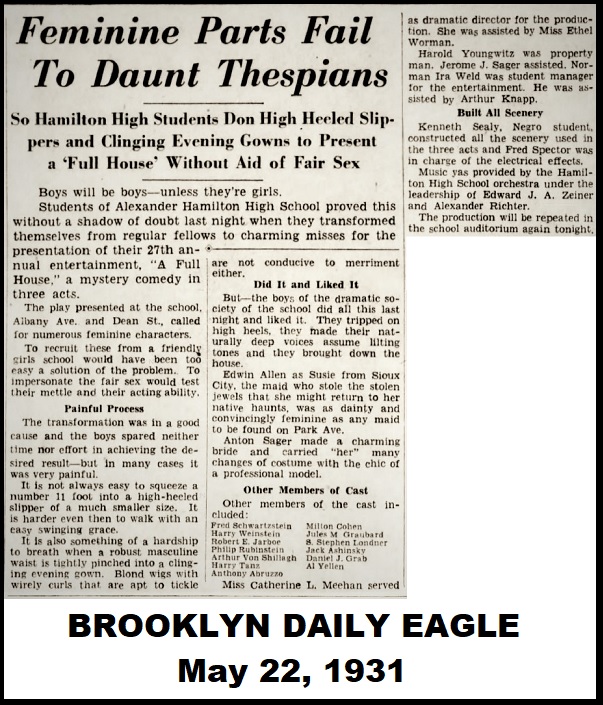

Young Anthony thrived. He became a Boy Scout, spending an entire summer when he was 12 years old at Camp Kanohvet in Pennsylvania. Early on he showed an interest in art and by the time he reached high school age, he was excelling in other areas as well. He attended Alexander Hamilton High School (formerly Commercial High), a vocational high school for boys on Albany Avenue. Among the activities he participated in was the drama society and when he was a sophomore he took part in a curiously-cast play that received quite a bit of attention in the local newspaper.

“Boys will be boys–unless they’re girls.”

“Students of Alexander Hamilton High School proved this without a shadow of a doubt last night when they transformed themselves from regular fellows to charming misses for the presentation of their 27th annual entertainment, “A [sic] Full House,” a mystery comedy in three acts.”

“The play presented at the school…called for numerous feminine characters.”

“To recruit from a friendly girls school would have been too easy a solution of the problem. To impersonate the fair sex would test their mettle and their acting ability.” [“Feminine Parts Fail To Daunt Thespians,” BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, May 22, 1931.]

BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, May 22, 1931

But it was another of the liberal arts in which Anthony really made his mark. In April 1933, the winners of the annual national writing competition sponsored by the SCHOLASTIC magazine were announced and Anthony received honorable mention and a cash prize. The winners were announced in the April 29, 1933, issue of the SCHOLASTIC and their works published in SAPLINGS, a book published yearly to honor the talented students. Anthony’s four poems were: “Trees In Winter,” “Change,” “Little Italy,” and “Clown Of The Weeds.”

Tumbleweed become the nimble pointer of the wind,

Stumbling over shale and rock to beat some of his kind;

First he does a toe dance, then she stands upon his hands;

Seeds are just confetti as he throws them in the sands.

Beckoning to prairie dogs to have a game of tag,

Wrestling with mighty thorns until his branches sag,

Visiting Miss Fireweed to have a tête–tête,

Playing hide and seek between the cattle’s clumsy feet.

Traveling before a storm,

to dodge the lightning sword,

Dancing dizzy circles while the thunder roars accord;

Hurrying to nowhere over yellow prairie sands,

Staging grand finales,

after bowing to the stands.

[Abruzzo, Anthony, “Clown of the Weeds,” SAPLINGS, pg. 33, 1933.]

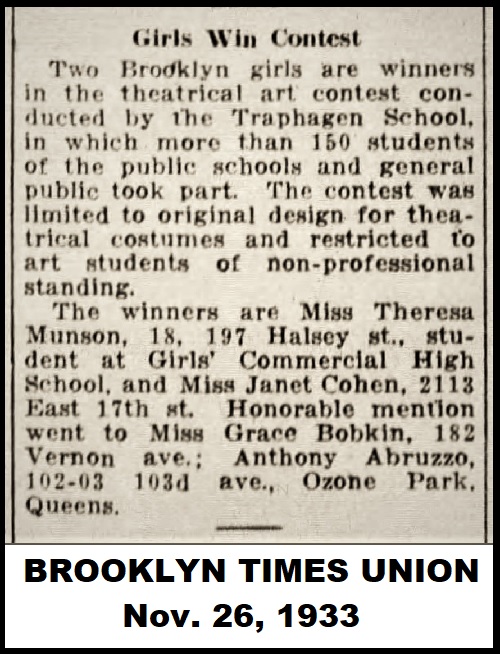

One month later, Anthony also was a winner in the city-wide poetry competition. His graduation from Hamilton High on June 30, 1933, did not end his streak of winning. In November, he was selected for an honorable mention in a contest run by the famed Traphagen School of Fashion in Manhattan.

BROOKLYN TIMES UNION, Nov. 26, 1933

This acclaimed design institute would turn out future illustrious clothing designers such as Geoffrey Beene, Anne Klein, and Gladys Parker, who would become even more famous as a cartoonist. Anthony was the only boy among the winners that year for theatrical costume design.

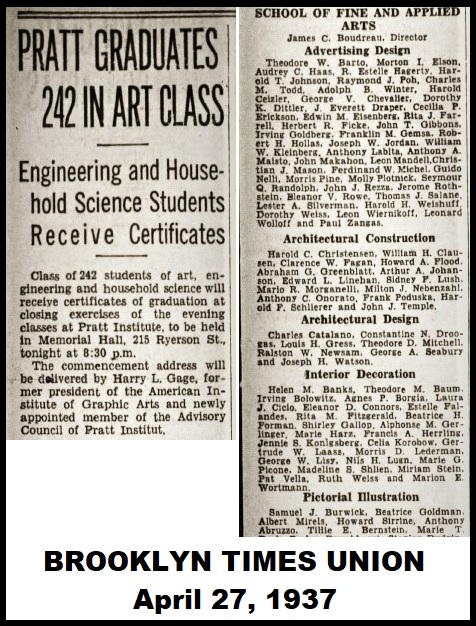

BROOKLYN TIMES UNION, April 27, 1937

Along with his honorable mention, Anthony was awarded a scholarship to Traphagen, where once again, he shined. While there, he won first prize in a life drawing competition.

Even though Anthony had found his calling with fashion design, to earn extra income while in school, he worked part-time jobs at a bookstore, a paper company and at Christmas time, he sold toys.

From Traphagen, Anthony entered the Pratt Institute. In April 1937, he received a certificate from Pratt in Pictorial Illustration, a major that would play an important role in his future.

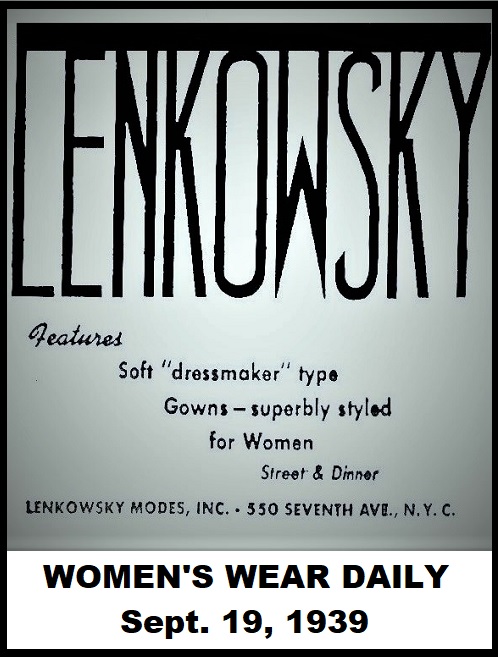

He finally entered the fashion industry when he was hired by Lenkowsky Modes in the Garment District of Manhattan. Employed as a designer of cocktail, street and dinner dresses that would be sold through Bonwit Teller and Saks Fifth Avenue, Anthony would claim he came by his design talent inherently, as both his aunt and his grandmother (on his father’s side) had been dressmakers. According to Anthony, his grandmother made marriage trousseaus for the royal Italian family.

WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY, Sept. 19, 1939

Curiously, Anthony adopted an alias for his design work. He was known as “Tony Pryor,” the last name a variation on the English translation of his stepfather’s name, “Priore.” Why the pseudonym? Was it an attempt to Americanize him and ward off any prejudice? That would seem to be an unnecessary concern in a city with so many Italians. Or was it to provide cover, and some distance, from his everyday life back in Ozone Park? What would the people of his neighborhood think of a young man who designed dresses for a living?

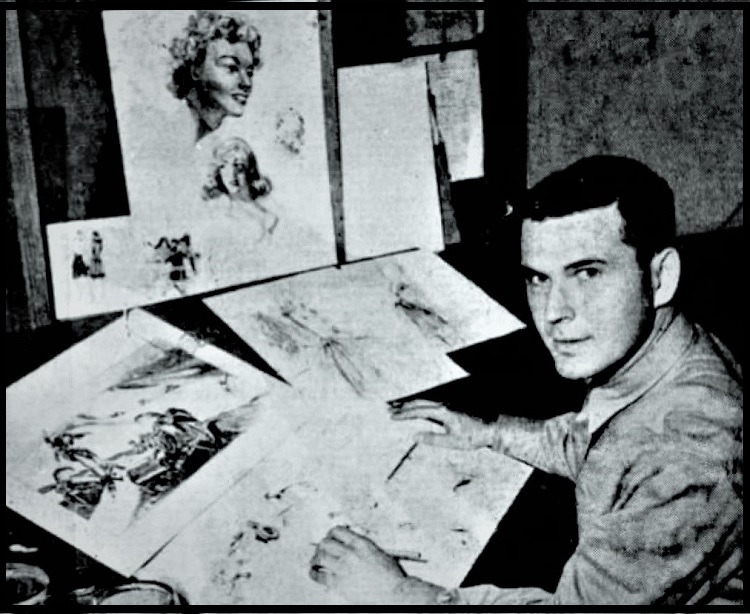

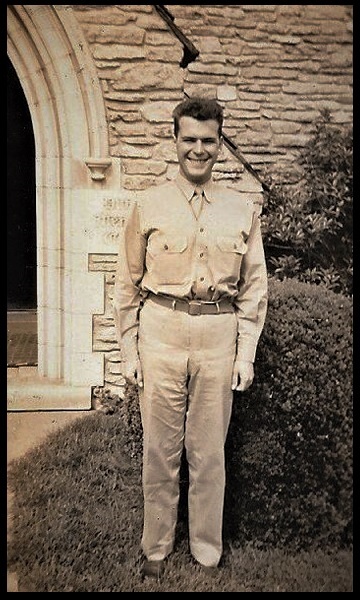

Anthony J. Abruzzo

But like most Americans, Anthony found his life uprooted with the outbreak of WWII.

“In addition to creating dress designs, he [Abruzzo] did fashion ads for the big stores and sold free lance sketches.”

“‘I was all ready to go to Paris,’ he said, ‘when the Nazi war machine changed my plans. Then I was called to service so I’ll have to forget about dress design for the duration.'” [“Dress Designer’s Doing Swell Illustrating Lines of Jeeps,” LONG ISLAND DAILY PRESS, Oct. 10, 1942.]

Anthony was a single, childless, male still living at home with his mother and stepfather when he entered the US Army on January 28, 1942. Sent to Camp Upton in Yaphank, New York, he endured the typical irritations and mundane duties expected of a new recruit.

“On his first day in the Army, he [Abruzzo] had D.P. for sixteen hours. The second day, on the train headed for [Fort] Knox, a captain tapped him on the shoulder and told him to report to the kitchen and serve coffee to the outfit. The third day a lieutenant tapped him on the shoulder and he served breakfast. The fourth day, after arriving at the fort, he looked at the duty roster and there was his name for K.P. at the top of the list. At this point it looked as if he would spend his entire Army career manning a potato knife.” [“Arms and the Girl Teach All Kinds of Tactics,” LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Nov. 14, 1943.]

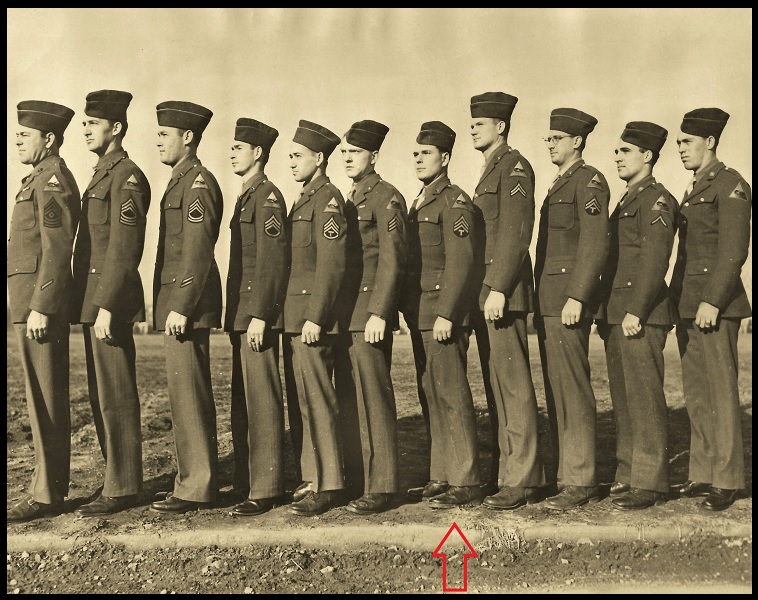

Technician 4th Grade, Sgt. Anthony Abruzzo, (7th from left)

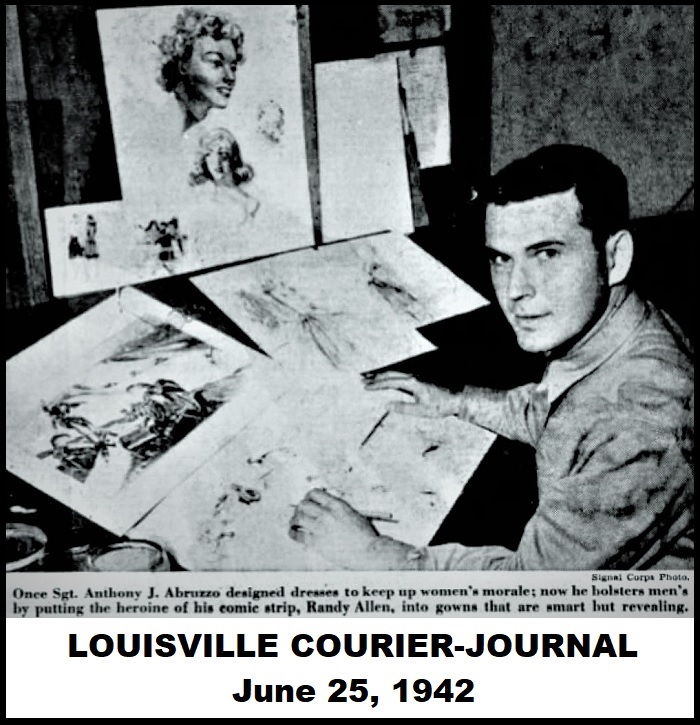

Soon, though, the Army realized Anthony’s talent and assigned him to its G-3 Section at Fort Knox near Louisville, Kentucky, to work on drawing material for the Armored Force Field Manuals. It also did not take long for the Army to realize the public relations value of having a dress designer in its ranks and Private Abruzzo quickly became the subject of numerous newspaper articles around the country.

LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, June 25, 1942

“When a gal goes dancing with the rugged ‘Armoraiders’ at the Service Club and hears the soldier whirling her around say, ‘That’s my dress you’ve go on,’ she has a right to think that riding in noisy tanks may affect a fellow.”

“That’s if she doesn’t realize her partner is Pvt. Tony Abruzzo, and that he’s neither ‘khaki-wacky’ nor ‘Army Happy,’ but an ex-dress designer whose creations hang in the closets of many of New York’s well-dressed women. Also, as a matter of record, Private Abruzzo doesn’t ride in tanks. He draws them.”

“When the war is over, Private Abruzzo expects to get back into design. He was all set to try his hand at something new for the Red Cross, but the uniforms already had been started.”

“Right now, all he can do is sketch in his spare time and page wistfully through Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Most of the time, including two or three evenings a week, is devoted to making Armored Force training manuals more intelligible to the men of Uncle Sam’s ultra-mechanized ground forces.” [“From Fabrics to Tanks,” LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, June 25, 1942.]

These tank filed manuals served a similar purpose to the ARMY MOTORS material Will Eisner was producing for the Army’s motor vehicle maintenance department. Anthony and the other Army artists were under the command of Lieut. Col. O. McCormick and the detailed process they followed was very specific.

“Colonel McCormick and his officers make rough sketches of the field problems and specific points about them to be illustrated. Following this, there’s a conference with the chief artist and chief draftsman.”

“Chief Artist John P. Miller of Cleveland, parcels out the art work to the other seven artists, and Chief Draftsman Paul Aman distributes the drafting. From this point, it’s a matter of constant checking and re-checking to see the weapons are the correct type, in the right positions, and place where they would be normally be in the problem. Mere symbols will not suffice to make an interesting and realistic presentation.”

“The men who do these drawings are ex-commercial artists. Sergt. Tony Abruzzo was a dress designer in New York City. He specializes in figures, still dashes fashion sketches in his spare time which he gives to admiring fellow workers. He is now working on a comic strip. His present soldier pay of $78 a month does not even approach his weekly salary as a civilian.” [Artists in Uniform Use Their Skill,” BALTIMORE SUN, Nov. 29, 1942.]

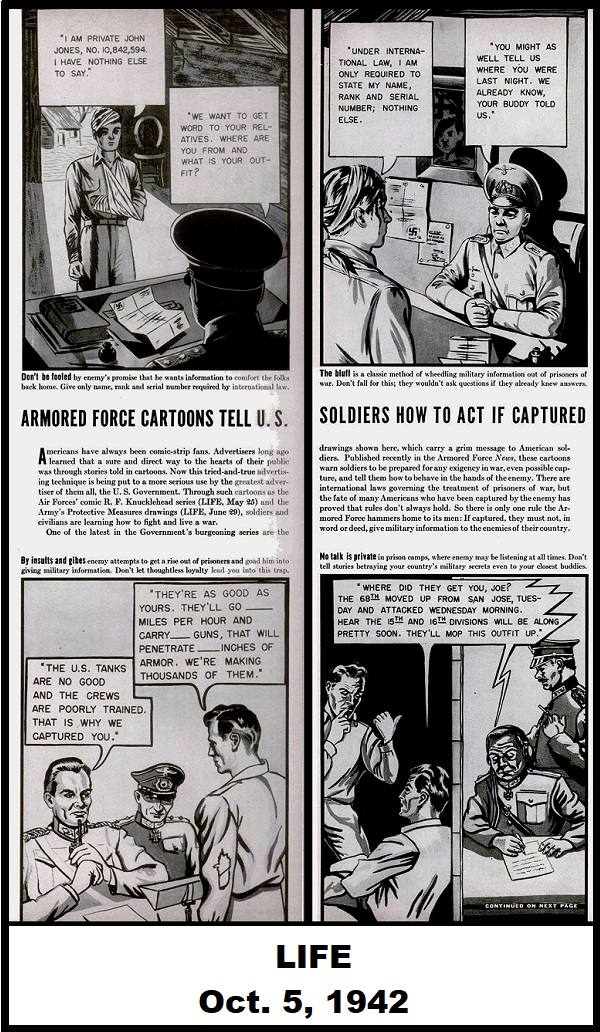

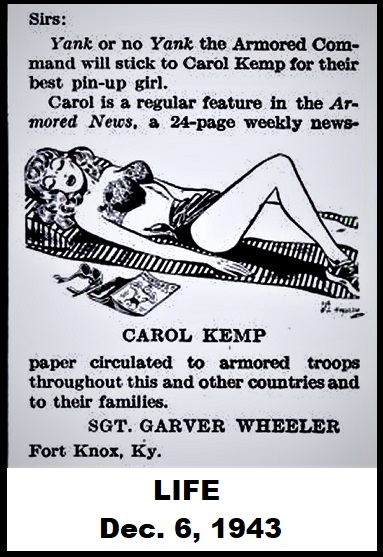

Not all of Anthony’s artwork went into the service manuals. Sometimes he was called upon to illustrate special material for the other publications such as the ARMORED FORCE NEWS. Usually these were in the form of cartoons dedicated to explaining particular subjects. A set of cartoons drawn by Anthony and another soldier caught the attention of LIFE magazine.

LIFE, pg. 1, Oct. 5, 1942

“One of the latest measures in the Government’s burgeoning series are the drawings shown here, which carry a grim message to American soldiers. Published recently in the Armored Force News, these cartoons warn soldiers to be prepared for any exigency in war, even possible capture, and tell them how to behave in the hands of the enemy.” [“Armored Force Cartoons Tell Soldiers How to Act if Captured,” LIFE, Oct. 5, 1942.]

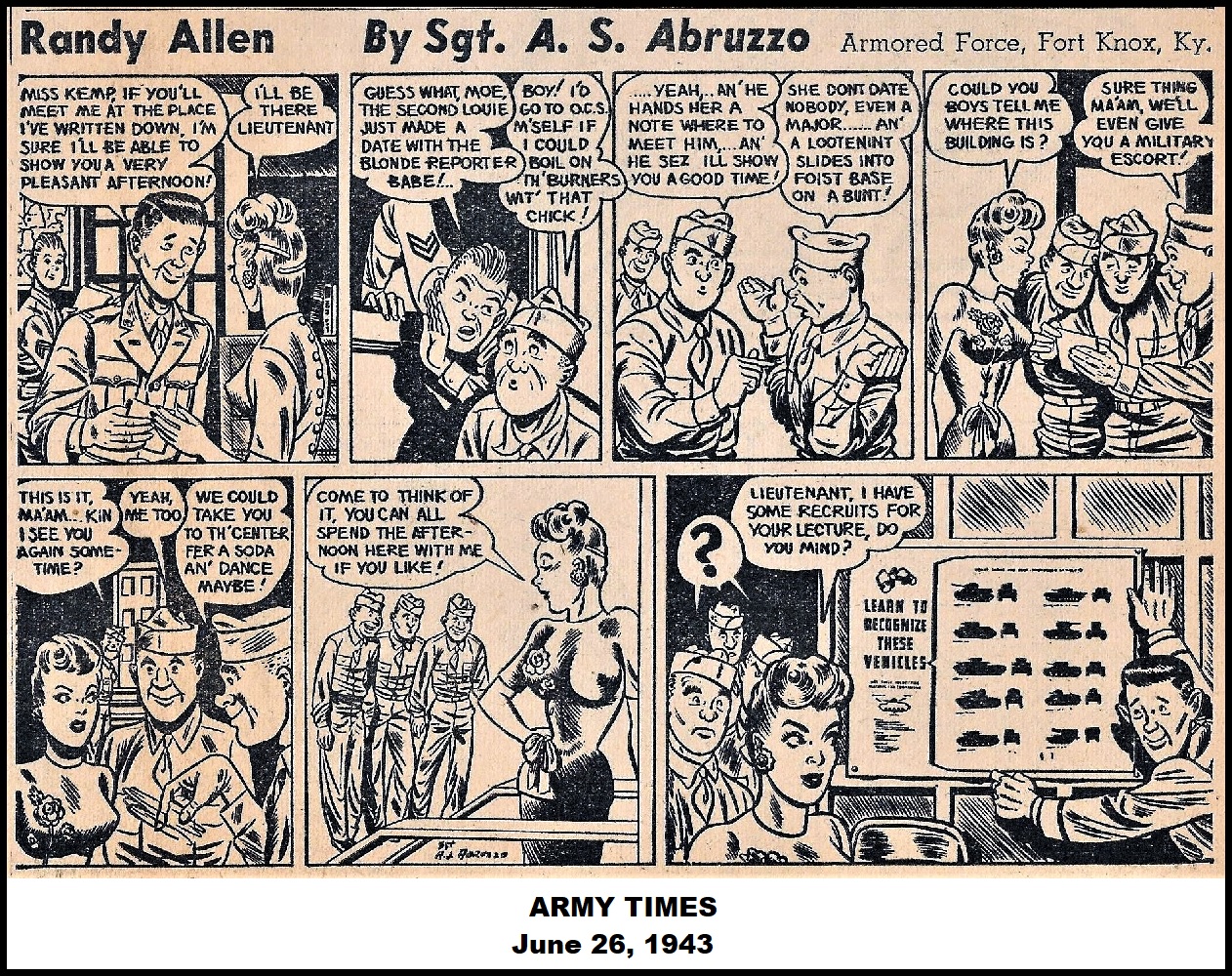

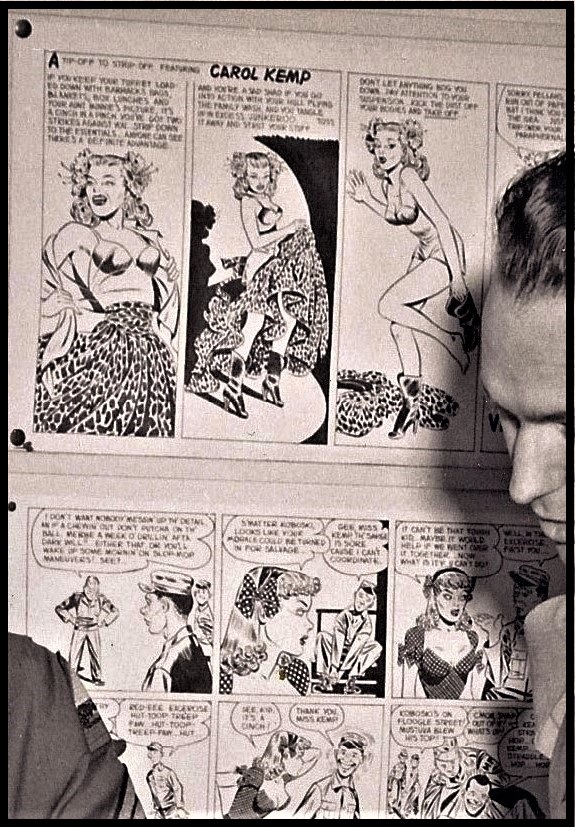

It wasn’t the field manuals or the instructive illustrations that would garner Anthony his most notoriety, though. It was a comic strip entitled “Randy Allen” that ran in both the ARMORED FORCE NEWS and ARMY TIMES.

ARMY TIMES, June 26, 1943

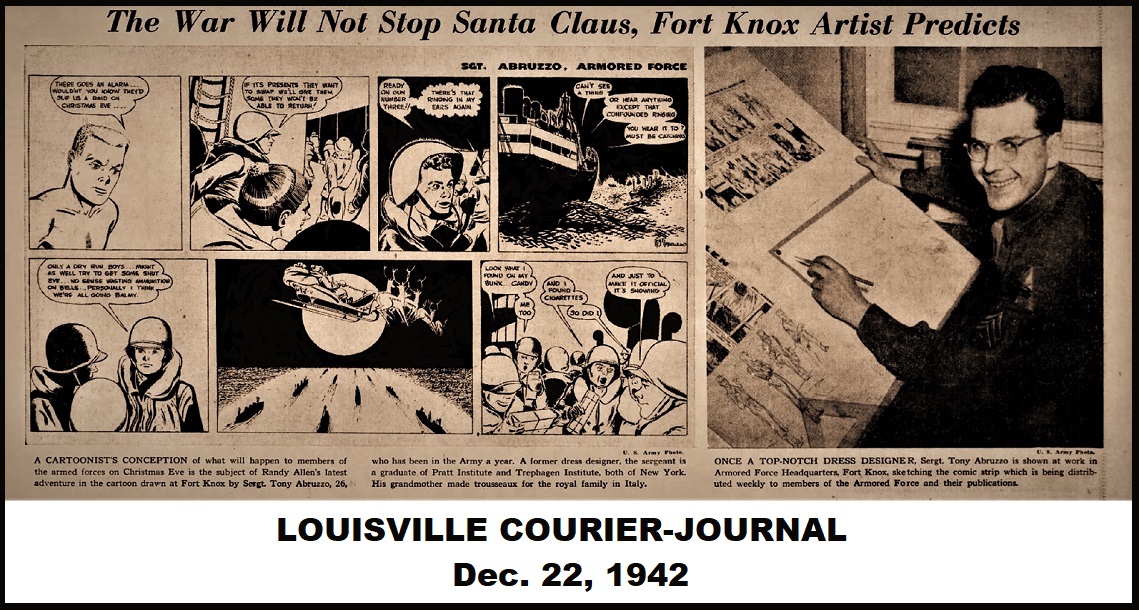

LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Dec. 22, 1943

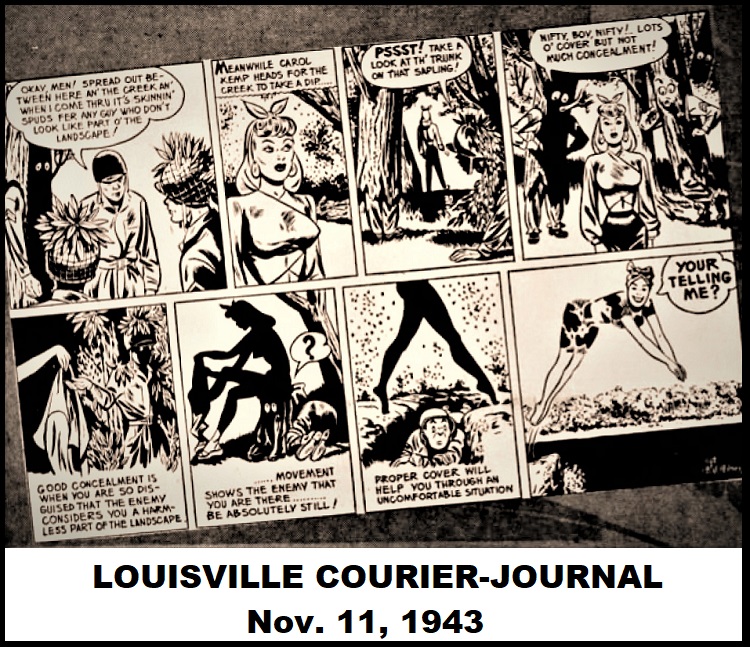

LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Nov. 11, 1943

Photo detail of ARMORED FORCE NEWS office showing “Randy Allen,” strip, circa 1944

“If you have ever seen the Armored News or the Army Times, you can’t have missed a comic strip called Randy Allen. You certainly noticed the spicy girl element. But what possibly escaped your attention, if you’re a layman in Armored Command matters, is that each strip depicts some point in tactical training. Many soldier comics have the girls, but Randy Allen is probably the only strip that contains the latter educational elements.” [Talley, Rhea, “Arms and the Girl Teach All Kinds of Tactics,” LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Nov. 14, 1943.]

LIFE, Dec. 6, 1943

Obviously, the author of this article was unaware of Eisner’s “Joe Dope” strip which also featured the comely “Connie Rodd” serving the same purpose as “Carol Kemp,” the girl cited in the article. Admittedly, although Anthony may not have possessed Eisner’s story-telling ability, his “Carol” was far more stylish than Eisner’s “Connie.”

Anthony was also given opportunity to display his artwork in exhibitions in the Louisville area. Again, he was singled out in newspaper articles for his unique story as well as for his talent.

“A dozen artists from the Armored School, Fort Knox, will exhibit more than eighty original cartoons and humorous illustrations at the Brown Hotel Friday and Saturday under the auspices of The Courier-Journal and Louisville Times and Kentucky Press Association.”

“Sgt. Anthony Abruzzo, comic strip artist, expects to show several of his original drawings. These will include preliminary sketches, revealing just how the strips are created. Sergeant Abruzzo’s feature, ‘Randy Allen,’ appears in the Armored News, the Armored Command’s weekly newspaper and the Army Times. A former fashion designer, Abruzzo’s style and draftsmanship are among the best in his field.” [“Armored School Artists to Exhibit 80 Original Cartoons at Brown Hotel,” LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Jan. 16, 1944.]

LOUISVILLE COURIER-JOURNAL, Jan. 16, 1944 (Abruzzo standing)

The war ended and so did Anthony’s military service. The exact date of his discharge is not known, but it can be assumed it was either late 1945 to early 1946. Even so, he may have stayed in the northern Kentucky area a while longer.

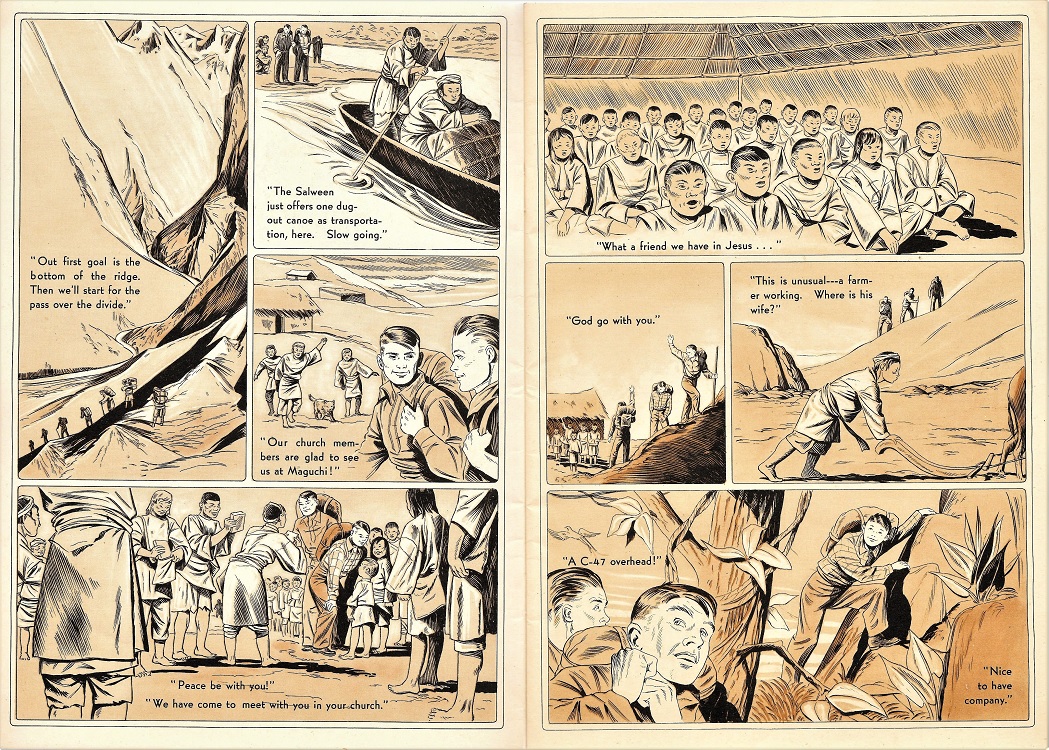

In August 1946, Standard Publishing of Cincinnati, Ohio released a comic book titled MISSION: RESCUE! The artist of this comic was Anthony.

Standard Publishing was a venerable publisher of religious material, having been founded in 1856 by a group of Protestant public figures, including future U. S. President James A. Garfield. Although it generally published books, Bible school material and CHRISTIAN STANDARD magazine, it had decided to expand into comic books, as several Catholic publishers had already.

The three-book series LIFE OF CHRIST VISUALIZED (1942-1943), was their first attempt in the format. While several years lapsed before their next comics appeared (likely due to paper limitations instituted during WWII), in 1946 they released LIFE OF JOSEPH VISUALIZED along with MISSION:RESCUE!

MISSION: RESCUE! (1946)

pgs2 & 3

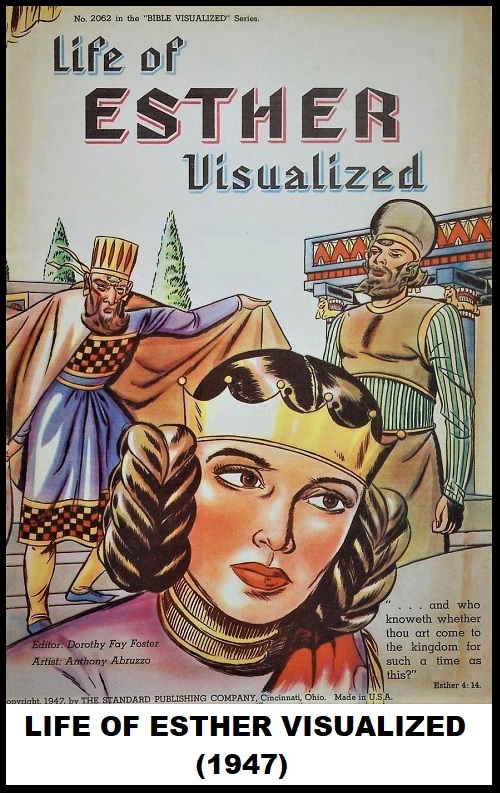

While all their previous comics were in color, MISSION: RESCUE! was printed in two tones of brown on a heavy paper and cost 35 cents. It contained 46 pages of artwork by Anthony as well as the front and back covers. The story was the story of Christian missionaries Russell and Gertrude Morse and their adventures among the people of Tibet and Burma. The comic adaptation was by Dorothy Fay Foster, a regular writer for Standard, who would also work with him on two other comics. Anthony and Foster teamed up on PARABLES JESUS TOLD and LIFE OF ESTHER VISUALIZED, both published in 1947.

LIFE OF ESTHER VISUALIZED (1947)

The artwork was certainly competent and Anthony likely could have found work in the newsstand comic book industry if he chose to. But his heart was in fashion design and it is a good guess that was the path he followed. If so, it has yet to be proven. Anthony Abruzzo virtually disappears.

Where did he go? What did he do? Tracing his movements are complicated by his name. “Anthony Abruzzo” is a frustratingly common Italian name, particularly in the boroughs of New York City. While his mother and stepfather continued to live in Ozone Park, the most likely Anthony Abruzzo I have found lived in Brooklyn.

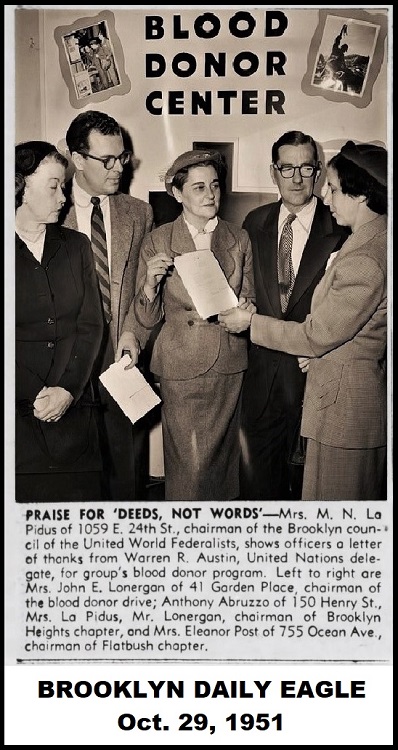

This Anthony Abruzzo lived at 281-A Henry Street, a townhouse in Brooklyn Heights and by 1951, in a similar residence right down the street at 150 Henry Street. I base this not only on the proximity to his former homes, but on two photographs.

BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, Oct. 29, 1951 (Abruzzo second from left)

Both of these photographs were taken in regards to this Anthony Abruzzo’s work with the United World Federalists. This organization was formed in the wake of WWII to encourage the nations of the world to form a federalist democratic government in order to prevent future wars. Anthony held several positions with this organization circa 1949-1951, including serving as president of its Brooklyn Heights chapter.

BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, May 23, 1949

No mentions, however, have been found regarding what he did for a living. Furthermore, nothing related to his personal life appeared in any of the local newspapers–a startling contrast to his notoriety during WWII. There was also one strange mention of a “Toni Abruzzo” in a short article, that refers to “her” giving a “backyard art exhibit” at her home in honor of the United World Federalists. There was no Toni, nor an Antoinette, Abruzzo in Brooklyn Heights at that time, so it probably was a reference to Anthony. If so, it was either an honest mistake, or possibly, someone at the paper making a cruel joke at Anthony’s expense.

Anthony Abruzzo’s earliest signed artwork in a newsstand comic book appears in SECRET HEARTS #12 (Oct.-Nov. 1952), published by Beverly Publishing, the romance comics imprint of DC Comics (National). In addition to the cover, Anthony drew the story, “Romance by Request.”

SECRET HEARTS #12 (Oct.-Nov. 1952)

y

SECRET HEARTS #12, last page of story.

From that point on, Anthony was a regular contributor to the DC romance line until about 1974. His artwork was polished, exquisitely rendered, illustrative drawings with a designers flair for composition.

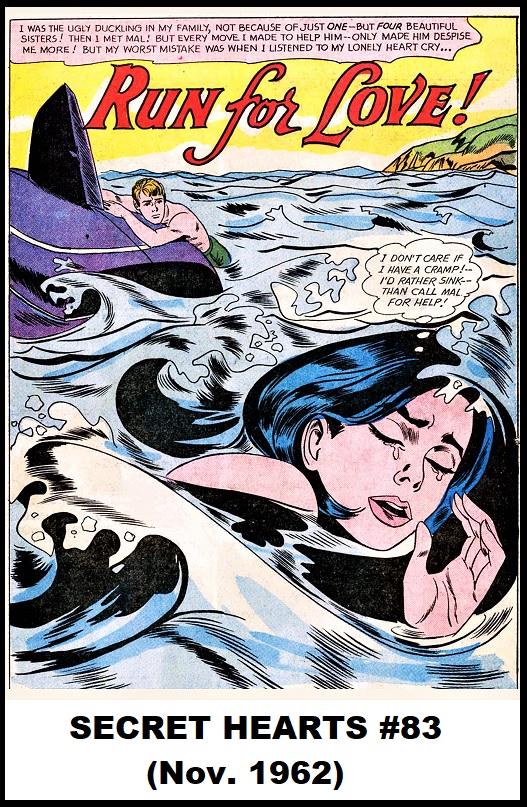

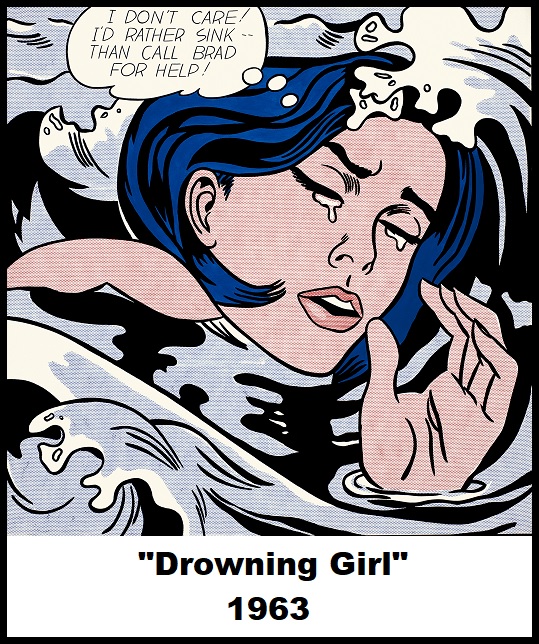

Anthony’s artistic talent was evident in all his work. So evident, in fact, that Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein used several of Anthony’s panels as the basis for several paintings. One of the most famous of these was the splash page from an Abruzzo story in SECRET HEARTS #83 (Nov.1962) that became the source for Lichtenstein’s 1963, Drowning Girl painting. Unwilling to credit Anthony for providing the basis of these works during his lifetime, Lichtenstein’s thievery has since been exposed and Anthony has received a bit of posthumous vindication.

SECRET HEARTS #83 (Nov. 1962)

“Drowning Girl,” 1963

________________________________________________

EPILOGUE:

The consummate professional, Anthony worked in virtual anonymity in the comics industry, unknown by name to his fans (he usually did not sign his work) and an enigma even to those who were employed by the same company.

One of the few who knew Anthony well enough to speak about him was Barbara Friedlander Bloomfield. As Barbara Friedlander, she got to know Anthony in the mid-1960s, first as an assistant to editor Jack Miller, who oversaw the romance comics for DC. Later, Friedlander became an editor herself and frequently used Anthony as one of her go-to artists. Recently, I contacted her and asked her for her memories of this talented, but little-known, artist.

Friedlander shared that she had “great memories of Tony Abruzzo…a lovely man with so much talent,” and “I wanted Tony to do more work for Me and Jack. Tony did all my Romance in Fashion pages and Mad Mad Modes for Moderns. This was on a monthly basis but what I dearly wanted was his beautiful work in romance stories. This did not happen.”

And she answered a lingering question regarding Anthony.

“Jack Miller, who was my mentor, always felt that Tony was gay.”

Much of Anthony’s story seemed to hint at his sexual orientation and if he was indeed gay, it may explain why he kept a low public profile and the distance he maintained between himself and his co-workers at DC. Most of Anthony’s life took place in times when gays were ostracized and shunned. While the fashion world was more tolerant, he likely would have had a hard time finding work in the comic book industry if his personal life became known.

A talent whose work was scarcely acknowledged by comics fandom, even Anthony’s death was unacknowledged by an obituary. All that is known that Anthony Joseph Abruzzo died on December 30, 1990, in Brooklyn, where his life began.

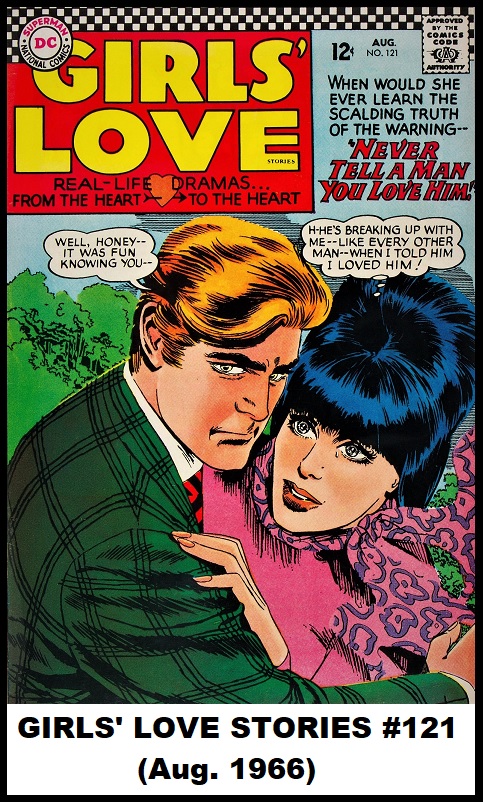

GIRLS’ LOVE STORIES #121 (Aug. 1966)