©2020 Ken Quattro

Virtually every comic fan with even a cursory interest in the history of the medium, knows the name of Dr. Fredric Wertham, psychiatrist, author and comic book critic. Just the mention of his name is enough to evoke some slanderous remark, a dismissive eye roll, a curse. But he wasn’t the first to criticize comics. Not by a long shot.

When Friedrich Wertheimer, aka Fredric Wertham, was still a schoolboy in Nuremberg, Germany, grumblings about “comic supplements” were already being heard.

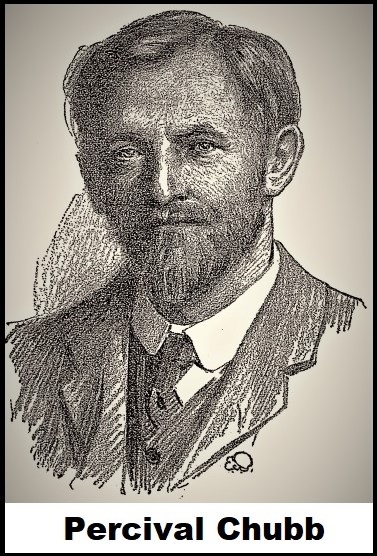

As the possessor of a perfectly Dickensian name, it’s probably no surprise that Percival Ashley Chubb was English. Born in the town of Devonport in 1860, Chubb was a low-level civil servant with a taste for socialist philosophy and a distaste for organized religion. He drifted into friendships with like-minded persons, including future playwright, George Bernard Shaw, which led to a group of them eventually forming the Fabian Society in 1884, with Chubb as its secretary.

The Fabians were democratic socialists, who believed that their goal of moving the British government toward socialism could be achieved through elections, rather than revolution as many Marxists preached. The Fabians were the forerunners of today’s Labour Party.

Chubb also took an interest in the Ethical Culture movement taking shape around the same time. Similarly disenchanted with traditional religions and capitalism, German-born Felix Adler evolved his secular humanist beliefs into a philosophy that held that morality was independent of theology, leading to the oft-stated maxim: “deed not creed.” Chubb became an ardent follower, joining the London Ethical Society in 1886, and in 1889, he moved to America to join Adler. He worked his way up the ranks and in 1897, Chubb became the Associate Leader of the Society for Ethical Culture of New York. It was while in that capacity that he began expressing his misgivings about the the evils of the “comic supplement” and he wasn’t alone.

As early as 1903, writer Walter T. Field was claiming that “There is in most children a stage, which begins at the age of about six or seven and lasts for several years, during which this desire for the extravagant, the uncouth, and the terrible sometimes becomes a passion. To fail to recognize the craving is usually to drive your children to satisfy it, sometimes surreptitiously, with the worst possible material,” he wrote.

“There is the grotesquely fearful and the grotesquely comic, and both have their fascination at this period. Your child will probably try your soul by discarding the artistic picture-books you have bought him and showing a decided preference for the adventures of ‘Buster Brown’ and ‘the Katzenjammer Kids,’ as depicted in vivid red, blue and yellow on the pages of the Sunday newspaper.”

“Discourage these pictures by all means’ but give him something good to take their place,–something really funny, that is bright without being lurid and comical without being vulgar.” [“The Illustrating of Children’s Books,” Walter T. Field, THE DIAL, vol. XXXV #420, Dec. 16, 1903.]

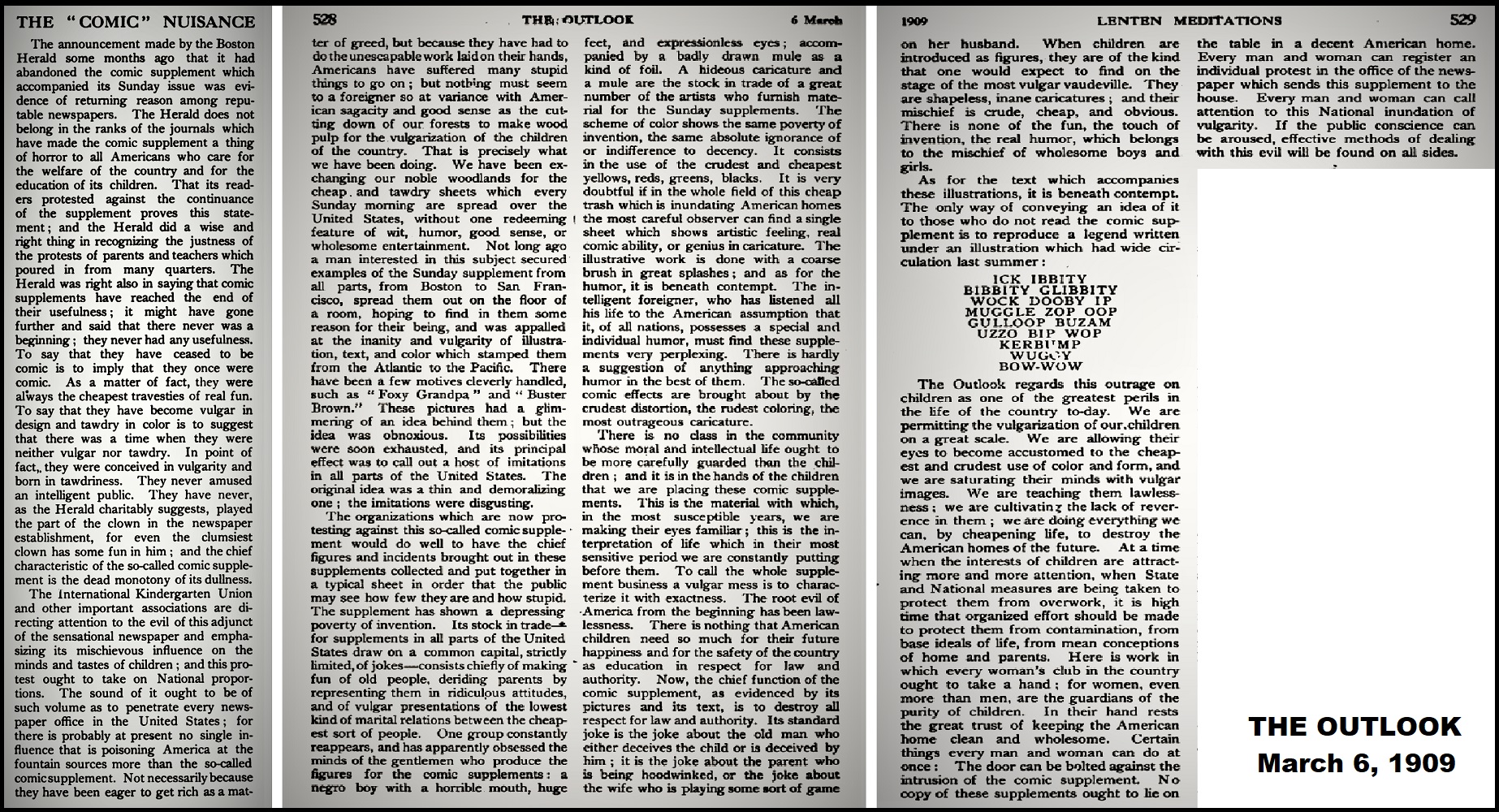

The complaints against the comics grew louder, with the weekly magazine, THE OUTLOOK, among the loudest. In an article lauding the pledge of one newspaper to no longer carry comic supplements and the efforts of the International Kindergarten Union for “directing attention to the evil of this adjunct of the sensational newspaper and emphasizing its mischievous influence of the minds and tastes of children,” wrote the author.

“The sound of [the protest] ought to be of such volume as to penetrate every newspaper office in the United States’ for there is probably at present no single influence that is poisoning America at the fountain sources more than the so-called comic supplement.” [“The ‘Comic’ Nuisance,” THE OUTLOOK, March 6, 1909.]

It was Chubb speaking before the national convention of the International Kindergarten Union in Buffalo in 1909, that brought the campaign targeting the comics into the public eye.

“I would ask what kind of atmosphere is spread about the home when the day begins with the Sunday newspaper, and is colored by the flagrant miscellaneousness, the loud secularity, the outrageous vulgarity of the typical Sunday sheet? In what frame of mind do we send to Sunday school the child whose first Sunday dainty has been the highly colored mixed candies of the colored supplement?”

“I sampled these last Sunday,” Chubb continued, “and I must say that I was struck once more by the feeblemindedness, the asininity of most of these distortions of humanity.” [“Convention Notes,” KINDERGARTEN-PRIMARY MAGAZINE, vol. XXI #9, June 1909.]

Chubb and others continued to stir the pot until in 1911, the League for the Improvement of the Children’s Comic Supplement was formed, with Chubb as its President.

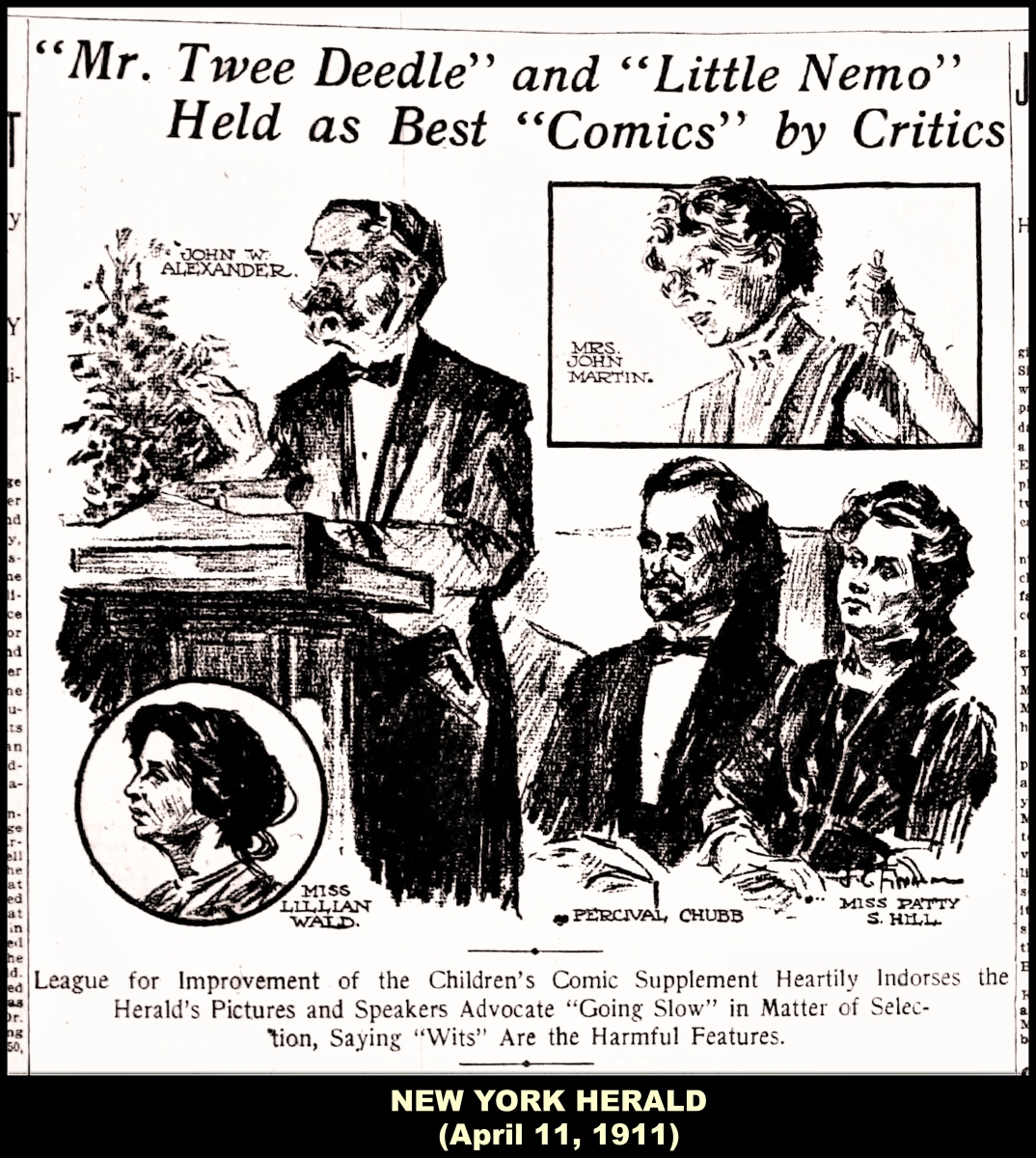

The League’s formation received widespread coverage, with most cheering its cause.

“A mass meeting under the auspices of the League for the Improvement of the Children’s Comic Supplement, in the Auditorium of the Ethical Culture Society, acted much in earnest last night,” began the TIMES article, “Percival Chubb presided. He read letters from educators, literary men and women, and artists which condemned as vulgar the comic supplement sheets which form a part of most Sunday newspapers here and in other cities.” [“Comic Supplements Publicly Denounced,” NEW YORK TIMES, April 7, 1911.]

Paraphrasing Chubb’s comments, the NEW YORK HERALD reported: “Mr. Chubb presented the rights of the child for fine, clean entertainment, for something that shall appeal to his nobler nature, and outline the plans of the league to further efforts to that end and to do all in its power to suppress the grosser kinds of ‘comics’ presented in some newspapers.” [“’Mr. Twee Deedle’ and ‘Little Nemo’ Held as Best “Comic’ by Critics,” NEW YORK HERALD, April 7, 1911.]

At the same mass meeting, two well-known artists, George de Forest Brush and John Alexander, rose up and defended comics strenuously.

“Some of the brightest men in America are working for the Sunday supplement,” said Alexander, “I can’t believe that they would do anything to harm children. The supplements? I take them all. My house is full of them. Of course some of them I throw away, but the rest we take delight in. If they are suppressed it would be a national loss.” [“Comics Sturdily Defended,” PITTSBURGH POST-GAZETTE, April 8, 1911.]

One proposal coming out of the meeting was for newspapers to submit the comics to the League for approval before printing them, much in the same way the Comics Code Authority would do for the comic book industry forty years hence. But eventually, the controversy subsided. The League didn’t last out then year and over time, the “comic supplement” and the comic strip, became an accepted and respected form of family entertainment.

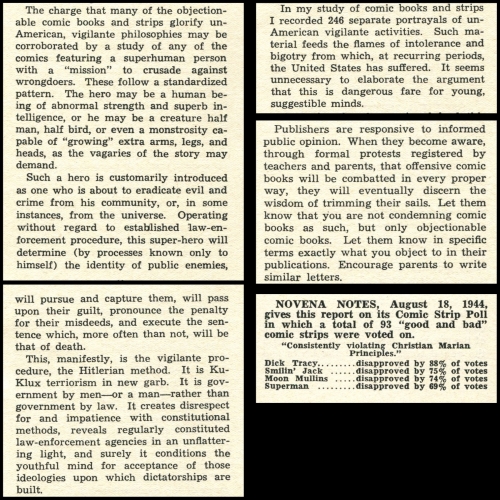

However, public media shaming found other targets. The film industry took the hits throughout the 1920s, leading to the Hays Office and the introduction of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1930. Outrage over the soft-porn magazines and pulps of the 1930s led to police crackdowns on the publishers and later that decade, sights set on the violence in children’s radio programs. Comic books fell beneath the critical gaze of reformers until the debut of “Superman” in early 1938 spawned a multitude of imitators. The appearance of so many super-powered vigilantes, muscle-flexing in skin-tight costumes, meting out varying degrees of physical punishment, made more than a few adults uneasy.

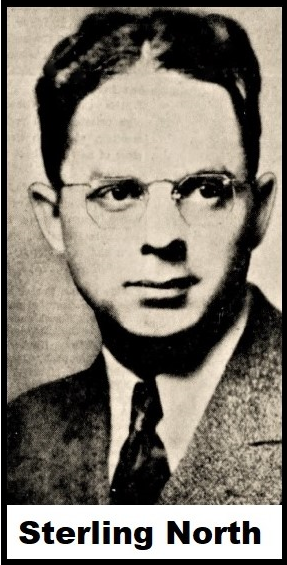

“Frankly, we were not perturbed when we first heard about the rise of the action ‘comics,’ Sterling North wrote, “We imagined (as do most parents) that they were no worse than the ‘funnies’ in the newspapers.”

“…we found that the bulk of these lurid publications depend fr their appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction—often with a child as victim. Superman heroics, voluptuous females in scanty attire, blazing machine guns, hooded ‘justice’ and cheap political propaganda were to be found on every page.” [“A National Disgrace,” Sterling North, July 14, 1940.]

While the irony of North citing comic strips as the respectable alternative to comic books was likely lost on most readers, his disgust with the medium was not. In that one column, he summarized the concerns that would frame the debate surrounding comic books for the next decade and a half.

As with the earlier controversy over other media, the criticism of comic books came mostly from educators, librarians, social reformers and religious institutions. Generally, each came at the “problem” of comic books in their own way. Educators and librarians condemned the adverse effects comics could have on children’s reading skills, sociologists focused upon the societal results and religious leaders had their moral concerns. Among that group, the outrage of the Catholic Church was most evident and the person probably most responsible for expressing those concerns to the faithful was the Rev. Louis A. Gales.

Father Gales was an assistant priest in St. Paul, Minnesota when he founded the CATHOLIC DIGEST in 1936. This monthly became the forum from which he assailed the dangers of Communism (prior to WWII) and went after the movie industry for the perceived negative influence their films had on children. By the early 1940s, his sight had settled on comic books. As with many critics, Gales saw both bad and good in the comic book format. He realized that by utilizing the medium to present approved behaviors and ideals, he could connect with young Catholics in a way they would understand. At the same time, he provided the way for church critics of the medium to attack comics. To that end, in 1942 he founded the Catechetical Guild Educational Society.

The most visible publications to come out of the Catechetical Guild were their TIMELESS TOPIX comic books. Starting in 1942, they were the cornerstone of the organization’s publishing efforts. Perhaps most famously, after WWII, when Gales returned to his attacks upon the creep of Communism, that led to the Guild’s publication of IS THIS TOMORROW?and other similarly-themed anti-Communist comics. However, despite their embracement of the medium, there were other publications directly aimed at the potential evils wrought by comic books that came out under the Guild’s guidance as well.

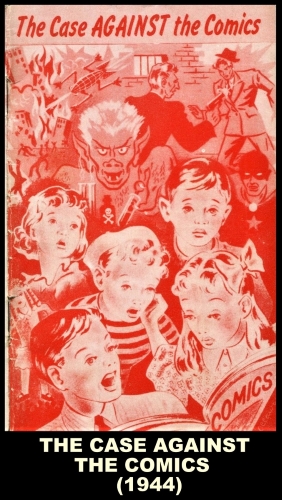

Gabriel Lynn was a Catechetical Guild staff member, usually tasked with studying newsstand comics and writing about his impressions of their content and effects. His study resulted in an article, “A Tragedy Caused by the Comics” that ran in the September 1944 issue of the CATHOLIC DIGEST and a booklet entitled, THE CASE AGAINST THE COMICS that same year.

“Mr. Lynn claims in analyzing comic books, he studied a total of 92, and in addition to these, more than 1000 newspaper comic strips appearing during the months of August, September and October 1943,” wrote columnist, Mae Saunders, “He asserts that he found the so-called ‘comic’ cartoons depicted 216 major crimes, and, in every instance, included detail sufficient to afford at least a working knowledge of the technique employed by the criminal or criminals.” [“Sharing Between the Shears,” Mae Saunders, March 11, 1944.]

These very same charges would be leveled loudly later in the decade by Dr. Wertham.

“Says Mr. Lynn: ‘The sensational exploits of individuals or groups engaged in executing masked and hooded justice have proved profitable for the purveyors of comic books, but this fact remains unshaken: No matter how despicable the villains against whom this ‘justice’ is aimed, no matter how triumphant the final defeat of vice by virtue, it is neither Christian nor American to permit the young to be taught in this way the pernicious totalitarian doctrine that the end justifies the means.” [Ibid.]

Lynn would go on to write other articles for the CATHOLIC DIGEST condemning comics and in early 1946, he was rewarded by Gales with the editorship of the newly founded POST-REPORTER.

“…the teen age newspaper for Catholic youth,” read one account, “a medium of expression, national in scope, through which Catholic youth may present a perfect picture of what they are doing, thinking, planning and accomplishing.” [“New Post-Reporter [Ca]ters to Teen Age,” OLEWEIN DAILY REGISTER, Feb. 13, 1946.]

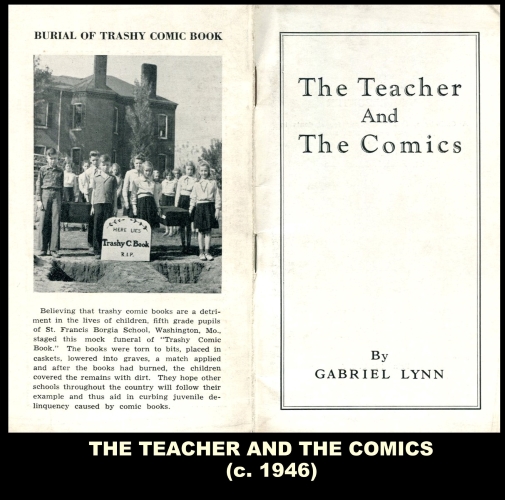

At the same time, Lynn also authored yet another booklet aimed expressly at the Catholic school teachers and parents. This new pamphlet, THE TEACHER AND THE COMICS, was published under the auspices of the POST-REPORTER and featured on its back cover a photograph of a Catholic school class standing behind two empty graves bearing a shared headstone reading, “Here Lies Trashy C. Book, R.I.P.”

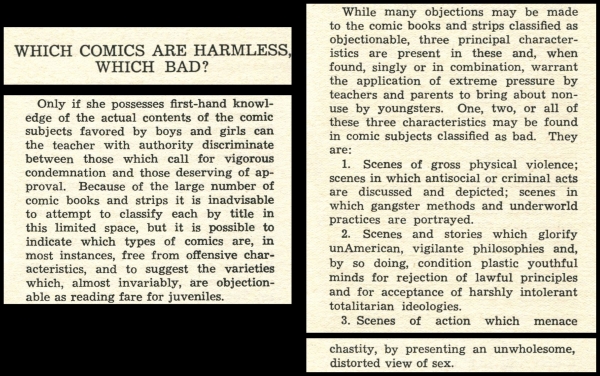

Lynn went into his charges in detail, heavily emphasizing the violent and sexual content of the “bad” comics. He also focused upon a chilling aspect which he claimed to have found in these comics that undoubtedly resonated with a populace just emerging from war.

“Such a hero is customarily introduced as one who is about to eradicate evil and crime from his community, or, in some instances, from the universe. Operating without regard to established law-enforcement procedure, this super-hero will determine (by processes known only to himself) the identity of public enemies, will pursue and capture them, will pass upon their guilt, pronounce the penalty for their misdeed, and execute the sentence which, more often than not, will be that of death.”

“This, manifestly, is the vigilante procedure, the Hitlerian method. It is Ku-Klux terrorism in new garb.” [Lynn, Gabriel, THE TEACHER AND THE COMICS, pp. 10-11. 1946.]

In conclusion, Lynn tempers his complaints about ‘bad’ comics with the usual recommendation that parents write publishers and let them know that “you are not condemning comic books as such, but only objectionable comic books.” [THE TEACHER AND THE COMICS, op. cit., pg. 15.]

Evidently, Lynn’s words had some effect, as staged ‘bad’ comic book burials and burnings occurred over the next several years. His efforts,though, have been largely forgotten due to the publicity campaign of Dr. Wertham, who, by 1948, had effectively become the face of comics criticism, using basically the same arguments as Lynn.

For his part, Lynn drifted into obscurity. Later in 1946, a memo was sent out by the Catholic Press Association concerning Lynn and his activities.

“TO ALL ACTIVE MEMBERS:–A writer, representing himself to be Gabriel Lynn, also using the names of Anthony Allen, Andrew Allen, A.G. Allen and A. Gallen, is canvassing Catholic editors looking for work. He has no authority to use the names if Father Barnes, Father Gales, Father Lord or the undersigned and we urge all members to be wary of cashing checks, okaying hotel bills, etc.” [“Editorial Information,” Catholic Press Association, Sept. 3, 1946.]

Percival Chubb continued his association with the Ethical Culture movement, serving as the long-time leader of the St. Louis Ethical Society and writing about a variety of subjects from socialism to drama to extolling atheism. In that vein, he is renowned as the author of the Atheist Christmas Carol.

On a related side note: There was a young woman who began working for the New York Ethical Society in the years soon after Chubb was making his assault upon the comic supplements. While her initial work centered around improving child labor conditions, she became an expert in the field of children’s reading matters, writing and lecturing for decades on the subject. In an ironic twist, this woman, Josette Frank, became the leading defender of comic books during the 1940s and 1950s and the longtime bête noire of Dr. Fredric Wertham.