©2020 Ken Quattro

Even before the United States entered the fighting during World War II, it was abundantly clear to those paying attention that the country lagged behind its potential adversaries in one crucial aspect of the coming conflict. The enemy had leading this effort, a man with a doctorate in philosophy and a reputation as a failed novelist, who had crafted the practice of propaganda to an art form.

“Political propaganda in principle is active and revolutionary. It is aimed at the broad masses. It speaks the language of the people because it wants to be understood by the people. Its task is the highest creative art of putting sometimes complicated events and facts in a way simple enough to be understood by the man on the street. Its foundation is that there is nothing the people cannot understand, but rather things must be put in a way that they can understand. It is a question of making it clear to him by using the proper approach, evidence, and language.” [Joseph Goebbels, Der Kongress zur Nürnberg, (1934)]

Inherent fears of an all-encompassing, Nazi-style propaganda ministry were outweighed by the American government’s concern that its citizens needed consistent messaging regarding war-related information. President Franklin Roosevelt’s response to this concern was to issue Executive Order 9182 on June 13, 1942, forming the Office of War Information (OWI).

The mission of the OWI was to coordinate a uniform narrative regarding the war effort and to communicate that to the public. This effort involved the various forms of media: radio, film, and print. To head up the OWI, Roosevelt appointed popular newsman, Elmer Davis.

Davis and the OWI took to their task immediately, and almost immediately, they engendered controversy with the issuance of a publication aimed at presenting “events and facts in a way simple enough to be understood by the man on the street.” A comic book.

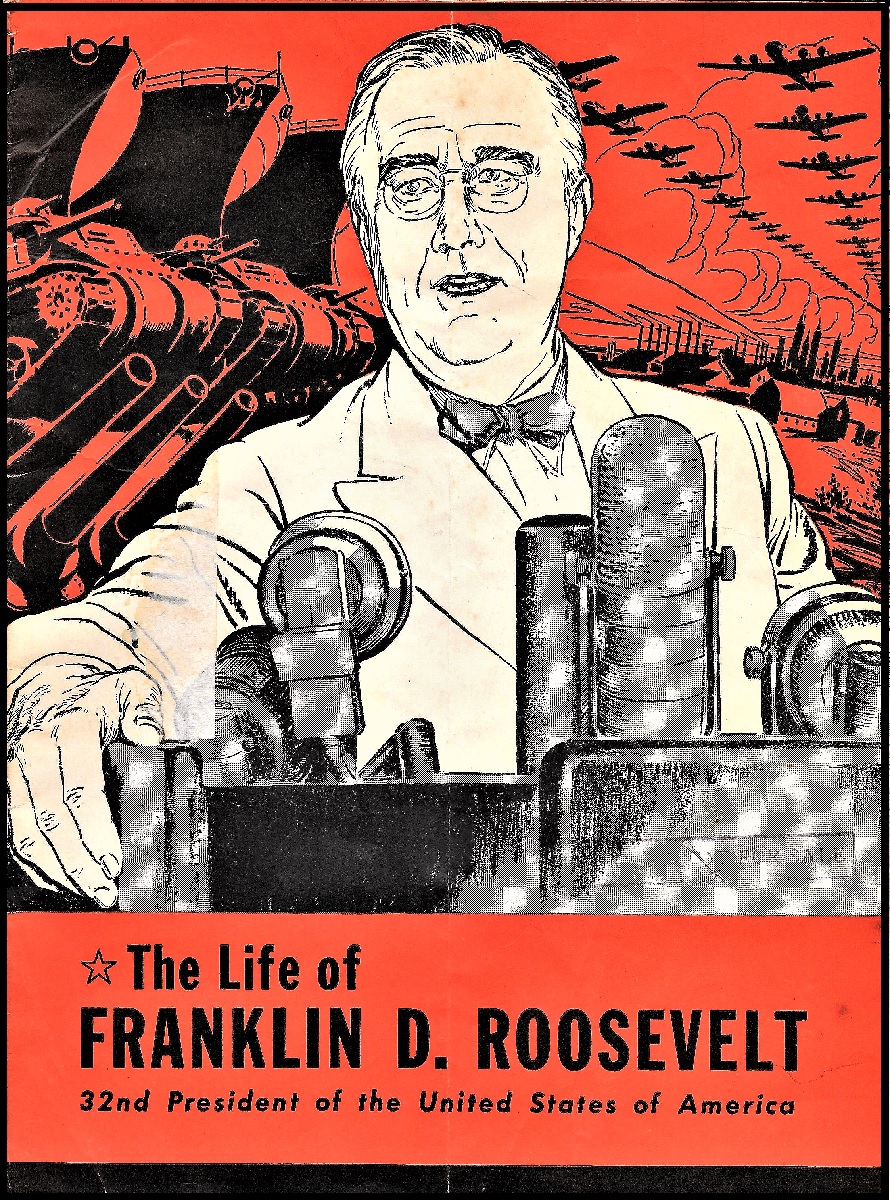

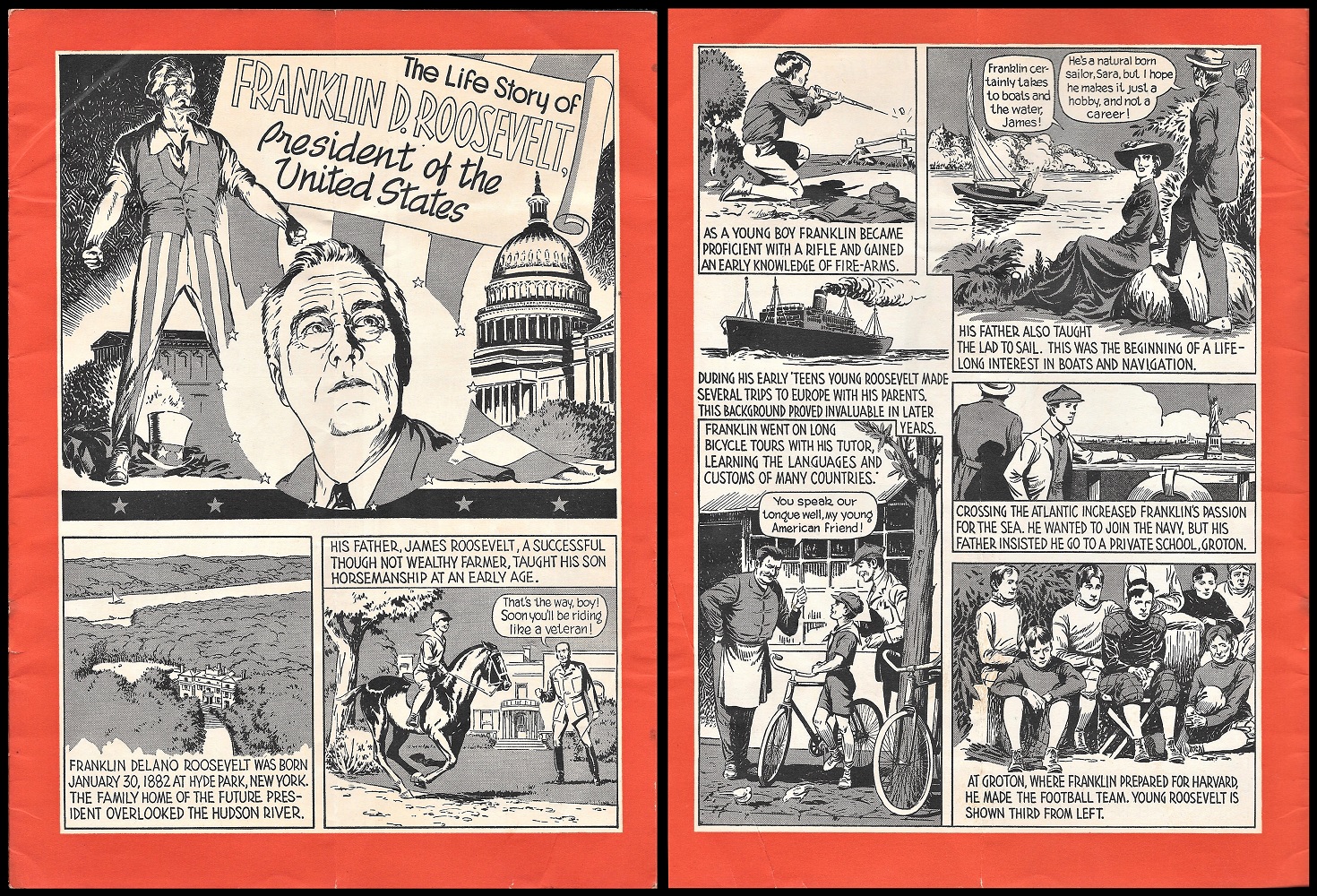

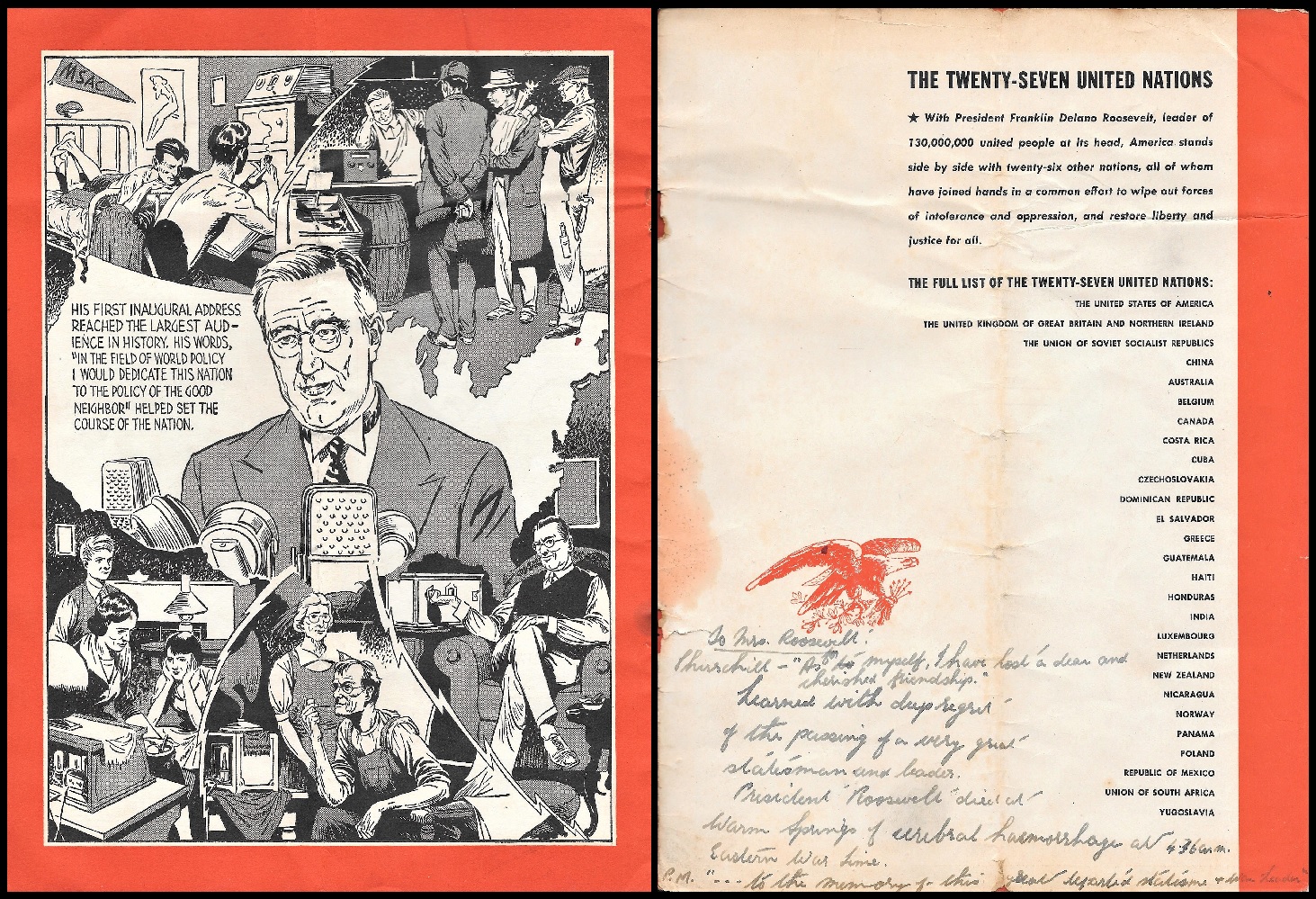

Although it had the same dimensions as a standard-sized Golden Age comic book, THE LIFE OF FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT (June 1942) differed from its contemporaries in that it was constructed with heavy paper covers and pages. Its uncredited illustrations were rendered in black and white, with red predominantly used on its covers and on the borders of its 16 pages. None of this was uncommon for a promotional booklet and certainly created no reason for concern. It was its content that caused the controversy.

pages 2 & 3

pages 4 & 5

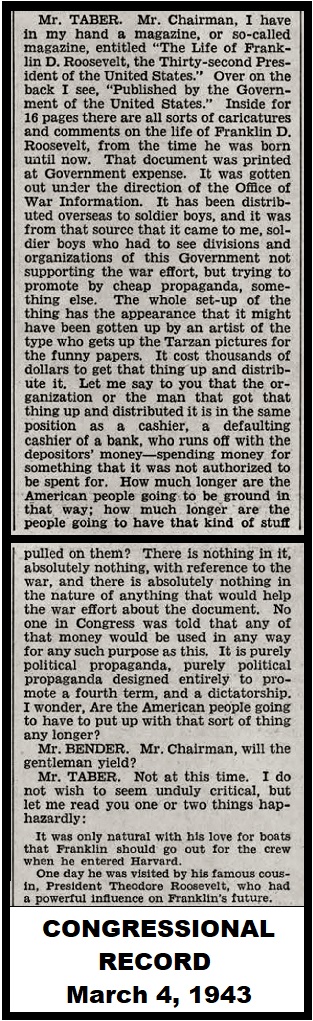

“Mr. Chairman, I have in my hand a magazine, or so-called magazine, entitled “The Life of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Thirty-second President of the United States,” began Congressman John Taber, of New York, “Over on the back I see, “Published by the Government of the United States.” Inside for 16 pages there are all sorts of caricatures and comments on the life of Franklin D. Roosevelt, from the time he was born until now. That document was printed at Government expense.”

VIE ILLUSTREE DE FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

“It was gotten out under the direction of the Office of War Information. It has been distributed overseas to soldier boys, and it was from that source that it came to me, soldier boys who had to see divisions and organizations of this Government not supporting the war effort, but trying to promote by cheap propaganda, something else.” [CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, pps. 1541-1542, March 4, 1943]

John S. Taber was notoriously parsimonious. The representative from Auburn, New York, served as the highest ranking Republican on the House Appropriations Committee, a position from which he critically scrutinized all governmental spending. Taber was also suspicious of anything related to Roosevelt, whom he viewed as imperious and leading the country toward socialism. In April 1935, when FDR’s plan for social security was debated on The Hill, Taber famously opined, “this bill was designed to fingerprint and enslave every worker of this land. Never in the history of the world has any measure been brought in here so insidiously designed as to prevent business recovery, to enslave workers, and to prevent any possibility of the employers providing work for the people.” [SOCIAL SECURITY ACT OF 1935, vol. 1, H.R. 7260, 74th Congress, 1st Session, Public Law 271, pg. 6054]

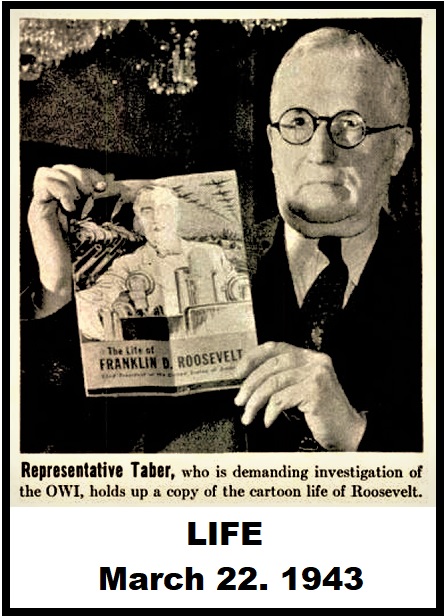

LIFE (March 22, 1943)

The OWI itself had been a particular target of Taber’s ire. He viewed its domestic agenda with a jaundiced eye and just one month previous, in February 1943, he had objected to the organization’s VICTORY magazine, which he termed, “a useless magazine,” and the space allocated to its shipping overseas, “better be filled with bombs or bullets for [use against] our enemies.” [“OWI Magazine Severely Criticized,” AP wire story, Feb. 10, 1943]In particular, Taber and other Republicans questioned the true mission of VICTORY since its debut issue contained an article entitled, “Roosevelt of America, President, Champion of Liberty, United States Leader in the War to Win Lasting and Worldwide Peace.” The Director of the OWI, Elmer Davis, agreed that the article “could have been better done,” but also defended it by asserting that it was impossible to publish a magazine for overseas distribution without, “saying something about the President.” [“OWI Magazine Severely Criticized,” ibid.]

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD (March 4, 1943)

Davis’ personal political history was problematic. He had once been a member of the American Labor Party, a socialist political organization, a fact that called his partisanship into question.

Davis’ assurances did nothing to assuage to the concerns of Republicans who viewed the OWI as a publicity machine for Roosevelt’s expected fourth term run in 1944. Indeed, THE LIFE OF FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT only fed that concern and provided the OWI’s critics with a lot of ammunition.

The opening panel of the comic depicted the visage of FDR between the two enduring symbols of the United States: the dome of the U.S. Capitol building and a tall, muscular, no-nonsense version of Uncle Sam. The pages that follow render the life of Roosevelt in carefully worded terms. One panel refers to his father James as a “successful, though not wealthy, farmer,” downplaying his actual affluence. An attempt, it can be assumed, to give FDR’s story a Lincoln-esque tone and to portray its protagonist as a “man of the people.”

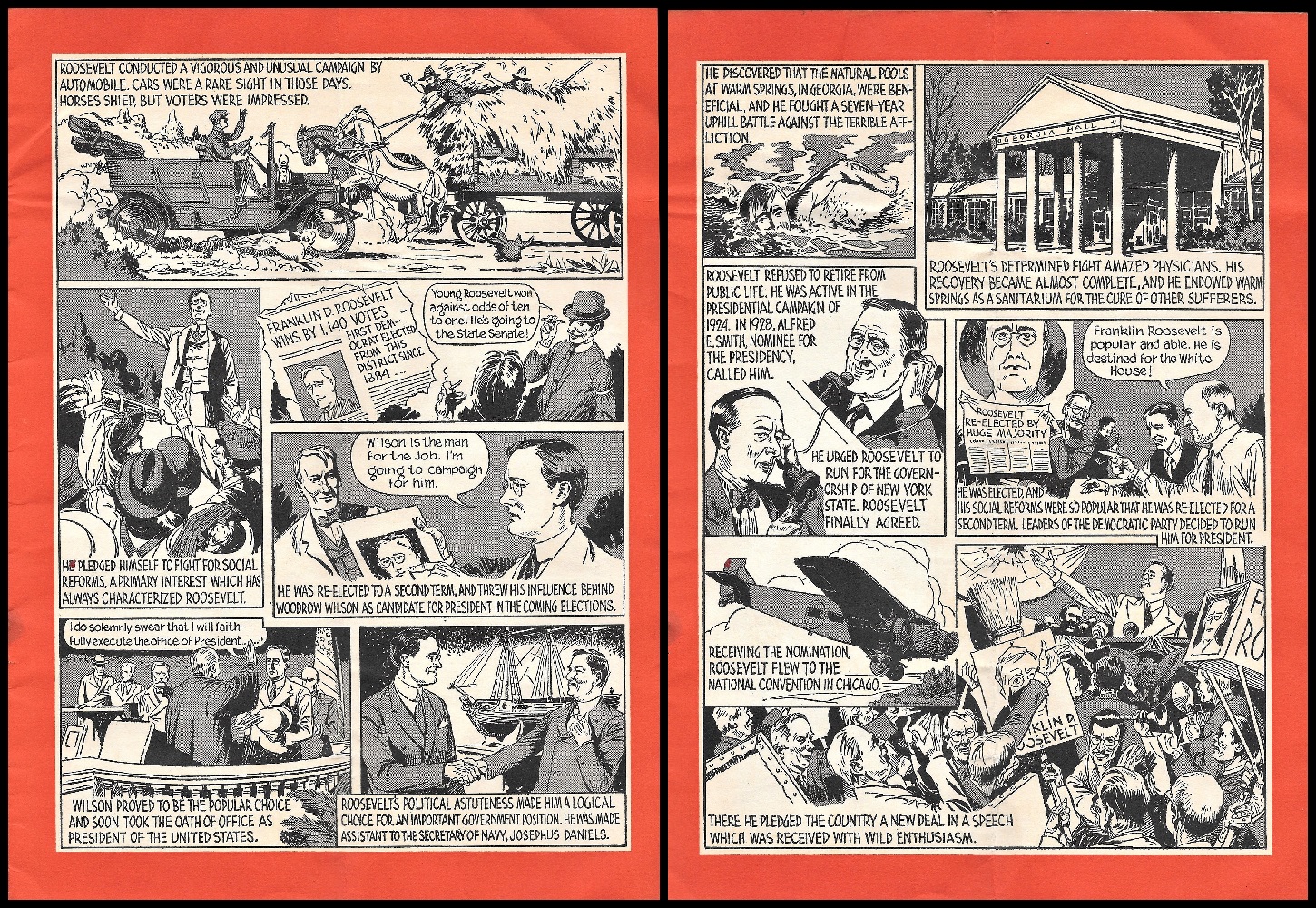

Each notable event in the young FDR’s life is given positive treatment, reinforced with text loaded with accolades for his achievements. His first run for political office was characterized as “a step which was to launch Franklin Roosevelt on a great career.” Each subsequent election notes his rising political ascendance and placed him in the thick of historical events. One panel depicted him resolutely confronting President Woodrow Wilson during World War I, and is captioned: “Always a man of action, Roosevelt demanded to be sent to sea and fight, but President Wilson refused the request.”

Even his first major political defeat, as the Democrat’s Vice-Presidential running mate of James Cox in 1920, is framed as “they lost a valiant campaign based on that dangerous issue” of supporting a League of Nations. When it came to the story of how Roosevelt contracted polio as the result of a fall into icy water, a caption solemnly noted, “Roosevelt’s courage was supreme.”

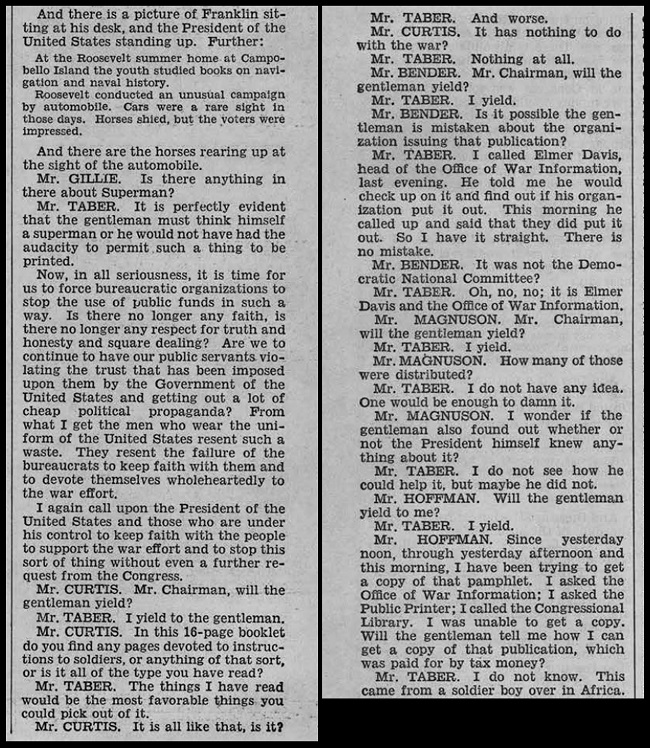

Such unabashedly laudatory language and heroic imagery grated the Republicans, a fact made evident by the following exchange during Taber’s remarks to Congress regarding the comic.“Is there anything in there about Superman?” asked Congressman George W. Gillie of Indiana, “It is perfectly evident that the gentleman [Roosevelt] must think himself a superman or he would not have had the audacity to permit such a thing to be printed,” replied Taber. [CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, op. cit.]

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, continued

But any complaints about the partiality of the FDR comic were facing an uphill battle. Roosevelt enjoyed an amicable, compliant relationship with the press. They looked the other way when it came to covering his affair with Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd and avoided mentioning, or showing him, in a wheelchair, despite his reliance upon it. And except for a short period when Roosevelt’s approval rating dipped below 50 percent for the first time since George Gallup began monitoring it in October 1937, from 1937 to 1943, FDR averaged a 65 percent approval rating. [“Economic Class and Popular Support for Franklin Roosevelt in War and Peace,” Matthew A. Baum and Samuel Kernell, PUBLIC OPINION QUARTERLY, vol. 65 #2 (Summer 2001), pps. 198-229]

There was one more factor working against the Republicans. As Abraham Lincoln noted years before, Americans were reluctant to change Presidents during wartime.

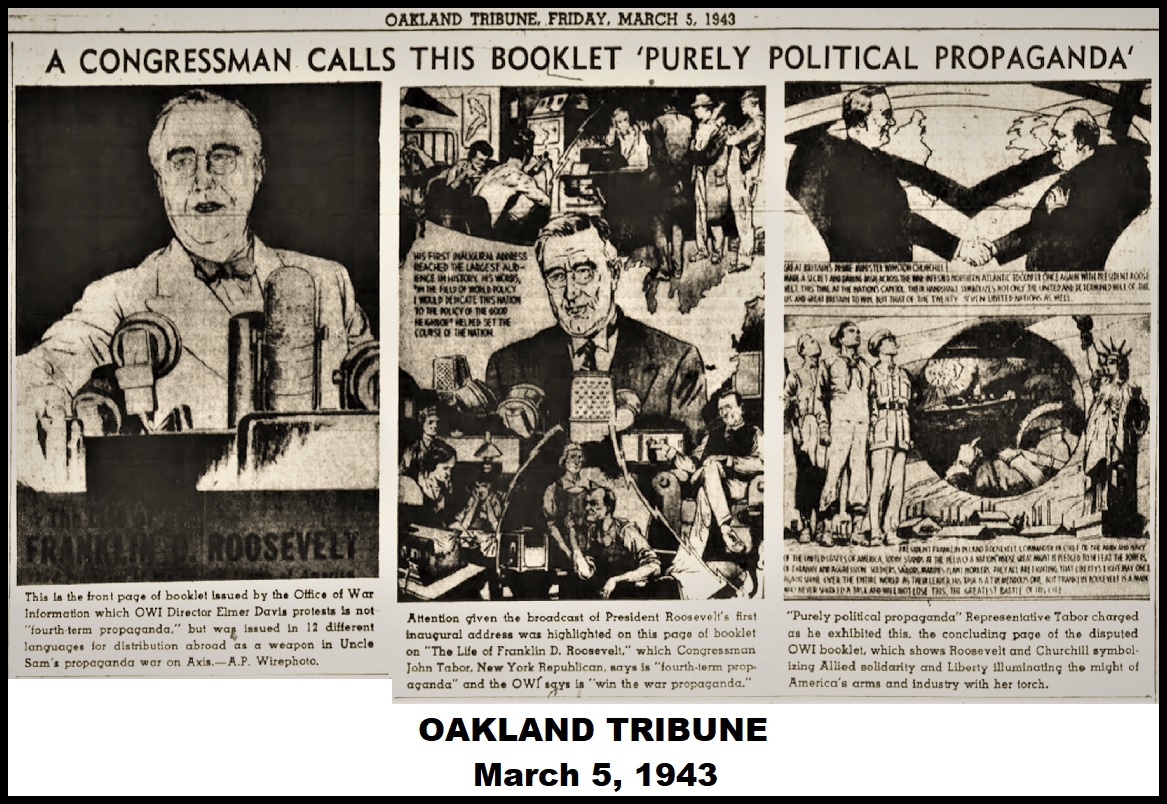

Still, when Taber made his comments before Congress on March 4, 1943, it was an explosive charge. The next day, newspapers all around the country carried the story and for the first time in history, a comic book became front page news.

“OWI Pamphlet on Life of Roosevelt Assailed by Congressman Taber,” read one headline, ‘Booklet Printed to Aid 4th Term, Taber Declares,” read another. “FDR ‘Tarzan Book’ Flayed, Probe Asked,” read yet another, playing off Taber’s charge that “the whole set-up of the thing has the appearance that it might have been gotten up by an artist of the type who gets up the Tarzan pictures for the funny papers.” [CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, op. cit.]

Most of the commentary on the booklet fell into partisan camps, with Democrats and liberal-leaning papers denying any partiality, while Republicans and conservative members of the press only seeing the opposite.

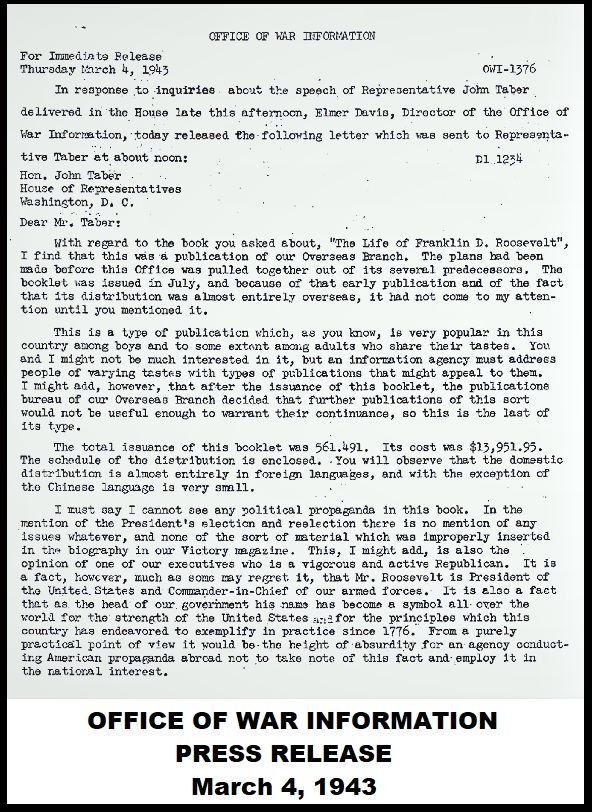

For their part, the OWI and Director Davis wasted little time in responding to Taber. By noon of the day Taber leveled his charges before Congress, Davis had penned a personal response to the congressman and also released it to the media.

OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION PRESS RELEASE (March 4, 1943)

“This is a type of publication which, as you know, is very popular in this country among boys and to some extent among adults who share their tastes,” Davis wrote, “You and I might not be much interested in it, but an information agency must address people of varying tastes with types of publications that might appeal to them.” Despite his defense of the comic, Davis added that policy changes had been made since its publication. “I might add, however, that after the issuance of this booklet, the publications bureau of our Overseas Branch decided that further publications of this sort would not be useful enough to warrant their continuance, so this is the last of its type.”

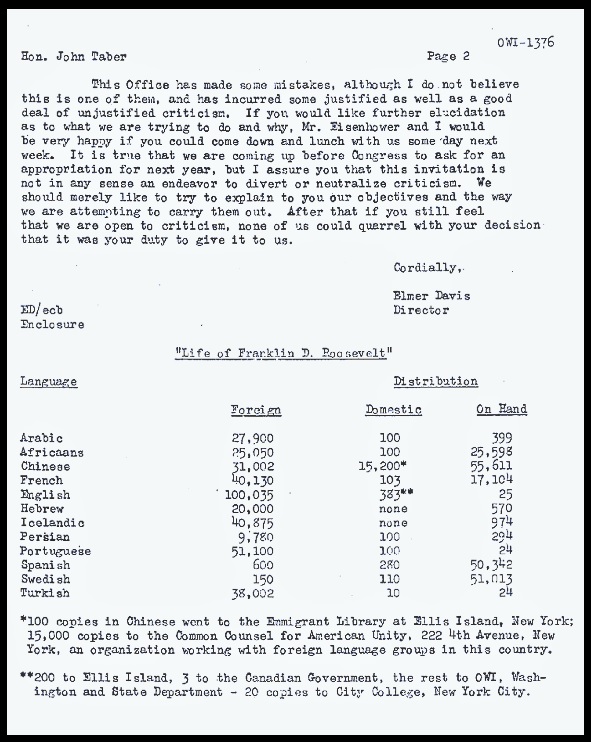

OWI PRESS RELEASE, page 2

After sharing details of the comic’s print run and total cost, Davis included a long paragraph expressing surprise over Taber’s claims about it being “political propaganda” and offered the rationale used in choosing Roosevelt as the subject of the booklet.

“I must say I cannot see any political propaganda in this book,” Davis stated, “In the mention of the President’s election and reelection there is no mention of any issues whatever, and none of the sort of material which was improperly inserted in the biography in our Victory magazine…” An acknowledgment of the earlier OWI publication that had drawn similar partisan complaints and that had resulted in an apology.

Davis noted that one of the OWI’s executives–”a vigorous and active Republican”–agreed with that perception, although he didn’t identify this person by name.

“It is a fact, however, much as some may regret it,” he continued somewhat sarcastically, “that Mr. Roosevelt is President of the United States and Commander-in-Chief of our armed forces.”

“It is also a fact that as head of our government his name has become a symbol all over the world for the strength of the United States and for the principles which this country has endeavored to exemplify in practice since 1776. From a purely practical point of view it would be the height of absurdity for an agency conducting American propaganda abroad not to take note of this fact and employ it in the national interest.” [Office of War Information news release, March 4, 1943]

OAKLAND TRIBUNE (March 5, 1943)

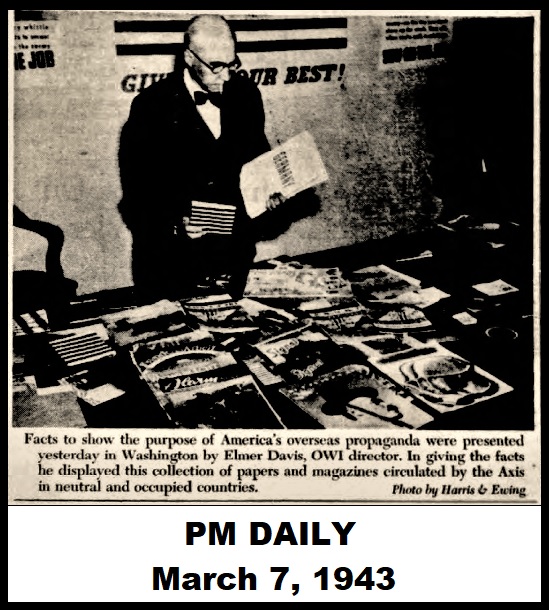

The observation that the President of the United States was basically a living embodiment of the nation itself is historically questionable. But it was a view shared by many at the time and found many supporters. One such example came with the coverage of a press conference Davis held on March 6th.

He stood behind a table full of Axis propaganda as a visual aid to show what the OWI was trying to confront with its material distributed in neutral countries overseas. Davis made sure to invite Taber to his presentation, an invitation that Taber ignored.

Gordon H. Cole, reported on Davis’ presser for the left-leaning newspaper, PM DAILY. He left no doubt how he felt. He pointedly noted that Davis called the press conference “to stop the Republican smear campaign.”

PM DAILY (March 7, 1943)

“Davis also pointed out the obvious,” Cole wrote, “To millions of people in this world, Franklin D. Roosevelt is a symbol of democracy and justice.”

“The pamphlet, by describing the life of its leading citizen, projected a picture of life in the U.S.A. and presented the nation’s foreign policy, Lend-Lease, the Atlantic Charter, etc. The cartoon device was used in an effort to appeal to a mass audience of any grade of literacy, particularly to youth.”

Cole didn’t mention the aspect of the comic that inflamed Republicans most: the almost mythical presentation of Roosevelt’s biography.

Brooklyn Democratic congressman Emanuel Celler was more blunt in his support of Davis’ contention and of the comic.

“To neutrals and Axis peoples, Roosevelt is the U.S. and the U.S. is Roosevelt. He is therefore our greatest propaganda asset. It would be asinine not to capitalize [on] such an asset.” [“Cellar Replies to Critics of OWI Pamphlets,” March 16, 1943]

Somewhat surprisingly, Davis and the OWI found a begrudging ally in the pages of LIFE magazine, owned by noted FDR foe, Henry Luce. In an article intended to show how America lagged behind the Nazi propaganda makers, the unnamed writer opined:

“If hot tempered Congressman like Taber would concentrate on getting U.S. policy-makers to forge a clear, honest and trusted foreign policy, the OWI might one day be able to wield it effectively.” [“U.S. is Losing the War of Words,” LIFE, March 22, 1943, pg. 11]

To be sure, conservatives also had their voices heard. Columnist Mark Sullivan, warned that even though Davis emphasized that the FDR comic was intended for a foreign readership, copies of it had fallen into hands of American soldiers,whether intentionally or not. And those servicemen and women made up a substantial portion of the 1944 electorate.

“Some 11,000,000 voters will be in the armed services,” Sullivan wrote “This is nearly a fourth of the whole electorate.”

“These 11,000,000 will vote,” he continued, “The 11,000,000 will vote more surely than the rest of the electorate…All in all, whichever candidate next year tends to be favored prevailingly by soldiers is likely to win the election. Those 11,000,000 would be a happy hunting ground for campaign speakers and writers—if the campaign writers could reach them.” [“Mark Sullivan Warns Against Political Propaganda in Material Sent Men in Service,” Mark Sullivan, March 14, 1943]

Despite threats from Taber that he would hold hearings to look into the partiality of the OWI, they never took place. He did, however, get some bit of revenge. On June 19, 1943, while electing to maintain the foreign operations of the OWI, the combined House and Senate voted to de-fund its domestic branch, effectively, killing it.

Alabama Democrat, Senator Joe Starnes, voted with the majority and had these words to offer on the prospect of the domestic OWI’s demise:

“America needs no Goebbels sitting in Washington…”

BONUS FACTS: The comic, THE LIFE OF FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT was published in 12 languages, including Icelandic, Persian and Chinese as well as English. Of the 561,739 copies printed, 349,783 were distributed.

Last page with handwritten message on it

My personal copy was obtained from a seller in Great Britain. I don’t know the provenance of this particular comic, but I am taken by the handwritten notes on is inside back cover. There, transcribed in fountain pen, are selected phrases from Winston Churchill’s radio speech upon news of the death of Franklin Roosevelt. It even includes the time of Roosevelt’s death, 4:36 a.m., Eastern War Time. A touching bit of history in a witness’ own hand.