WINONA REPUBLICAN-HERALD (March 2, 1948)

©2019 Ken Quattro

Comic book defender, Josette Frank of the Child Study Association of America (CSAA) and Edwin Lukas, Executive Director of the Society for Crime Prevention, were in the audience on March 2, 1948, for the radio broadcast of “America’s Town Meeting of the Air.” A panel comprised of drama critic John Mason Brown, writer Marya Mannes, cartoonist Al Capp and publisher George Hecht of Parents’ Magazine Press were debating, “What’s Wrong with the Comics?”

NAUGATUCK DAILY NEWS (Feb. 28, 1948)

The comics controversy had been simmering for a while. Before WWII, critics such as columnist Sterling North had questioned the effect comic books were having on America’s children, but the advent of the war had placed such concerns on the back burner. Now, though, those concerns were beginning to emerge anew, with the additional “scientific” heft of noted psychiatrist, Dr. Fredric Wertham.

John Mason Brown, Marya Mannes, George V. Denny, Jr., Al Capp and George J. Hecht at the broadcast of “America’s Town Meeting of the Air,” NEWSDEALER (July 1948)

Wertham had a way of getting his name into the news, often as a defense witness for people accused of heinous murders. His founding of the Lafargue Mental Health Clinic in Harlem had provided him with social welfare credibility and, supposedly, material for his theories about the deleterious effects of comics. These criticisms initially gained notice in New York City when Wertham appeared on the local WNBC radio program, “Author Meets the Critics,” with John K. M. McCaffery back on January 23. Among the listeners to the show was Frank, and she was incensed enough to sit down and write to Wertham immediately after the broadcast.

Josette Frank (1938)

“I was greatly interested in your presentation this morning on the McCaffrey [sic] program concerning comic books and particularly in your statement that “99 % of the comics” contain obscene material.”

“I am wondering whether you would be good enough to let me know where I can locate the data on which this is based. It is certainly a very frightening figure to give parents and ought to be substantiated by sound data.”

“As you possibly know, I have been interested and concerned with comic books for a number of years as part of my work in the field of children’s reading. I have done considerable work with them and I thought I knew them pretty well, but it seems evident that you have made some studies or have access to data which I do not have and would like to study.”

“For the past year or so I have been concerned, as you are, about the growing number of new comic books with a sex interest. These are certainly an aberration of the earlier content of both comic books and comic strips. I should have guessed, roughly, without any careful tabulation that they comprise a fairly small percentage (though still too many) of the total number of some 250 titles on the news stands. I am amazed at the figure you find.”

“Will you be good enough to let me know the basis on which this conclusion was arrived at?” [Josette Frank letter to Dr. Fredric Wertham, Jan. 23, 1948.]

Frank was calling Wertham’s bluff. She had long been involved with study of the effects of comics upon children, having conducted research herself through her work with the CSAA. She suspected he was fudging his numbers. But Wertham couldn’t be bothered with replying to Frank personally, so he had his secretary T. B. Foster do it for him.

“Thank you for your letter. Dr. Wertham and his associates have been interested for some time in the question of comic books and related subjects. He wishes me to let you know that none of his data have been published as yet.”

“I might add that in examining the transcript of Dr. Wertham’s remarks on the McCaffery program I do not notice at any point the word “obscene.” [T. B. Foster letter to Josette Frank, Jan. 28, 1948.]

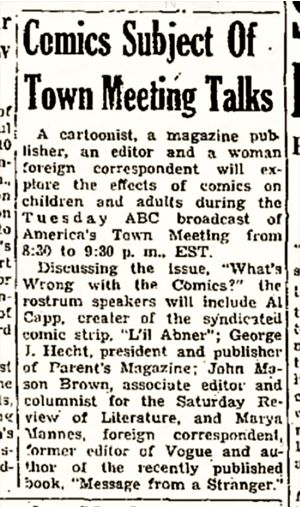

John Mason Brown

As is often the case in such forums, the debate consisted mostly of unswerving points of view with little to no consideration of the other side.

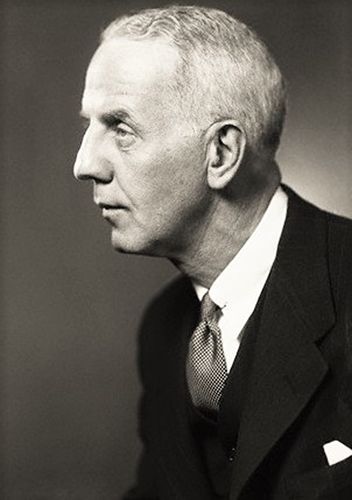

Befitting his profession, Brown led off with a dramatically haughty attack on comics that contained the infamously invective, “Most comics, as I see them, are the marijuana of the nursery! They are the bane of the bassinet! They are the horror of the home, the curse of the kids and a threat to the future!”

Soon after this broadcast, Brown’s comments during the debate were reprinted in his”Seeing Things” column in the SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE.

“If I hate the comics, I have my reasons. I know that, as part of a healthy diet, everyone needs a certain amount of trash. Each generation has always found its own trash.”

“What riles me when I see my children absorbed by the comics is my awareness of what they are not reading, and could be reading. I other words, of the more genuine and deeper pleasures that they could be having.” [“The Case Against The Comics,” John Mason Brown, SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, March 20, 1948.]

“The Case Against The Comics,” John Mason Brown, SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE (March 20, 1948)

When it came time for Hecht, publisher of TRUE COMICS, to respond to Brown’s comments, he lauded the virtues of “good” comics and quoted Frank by name to support his view. He went on to extol the potential of comic books as a learning tool.

George J. Hecht (1941)

“The United States Armed Services used the comics as a means of teaching soldiers and sailors how to operate various weapons and how to conduct themselves in battle. They found that soldiers and sailors learned more rapidly by means of comics.” [“Are Comics Good or Bad for Kids?” abridged transcript of “America’s Town Meeting of the Air” broadcast, NEWSDEALER, July 1948.]

But true to his previous comments on comics, Hecht also took time to point out those he viewed negatively.

“On the other hand, I admit there are a small percentage of comic magazines that I consider harmful to young readers. There are a number of comic magazines on the stands that are extremely sexy and unduly deal with the activities of criminals, which magazines I do admit are harmful to the young.” [Ibid.]

Hecht was followed by Mannes, who conversely denounced comics for being “not only a waste of time, but a waste of eyesight. With few exceptions, comics are very ugly–bad in drawing, bad in color, bad in print. The human beings in them are ugly even they’re meant to be handsome. Stalwart young men with coat-hanger shoulders and nutcracker jaws are travesties of the male. The bosomy, over-painted and abysmally vulgar women are travesties of the female. The so-called funny characters are merely repulsive.” [Ibid.]

Mannes also claimed that comics stunted intellectual growth, “A child grows by learning, by playing, and by dreaming. Comics supply none of these needs. They do not teach Mr. Hecht, unless you consider education a series of facts coated with the laxative of fiction. They’re not play,because the child is passive reading them. And they kill dreams. [Ibid.]

Mannes comments reiterated claims she had written the year before in a NEW REPUBLIC article attacking comics.

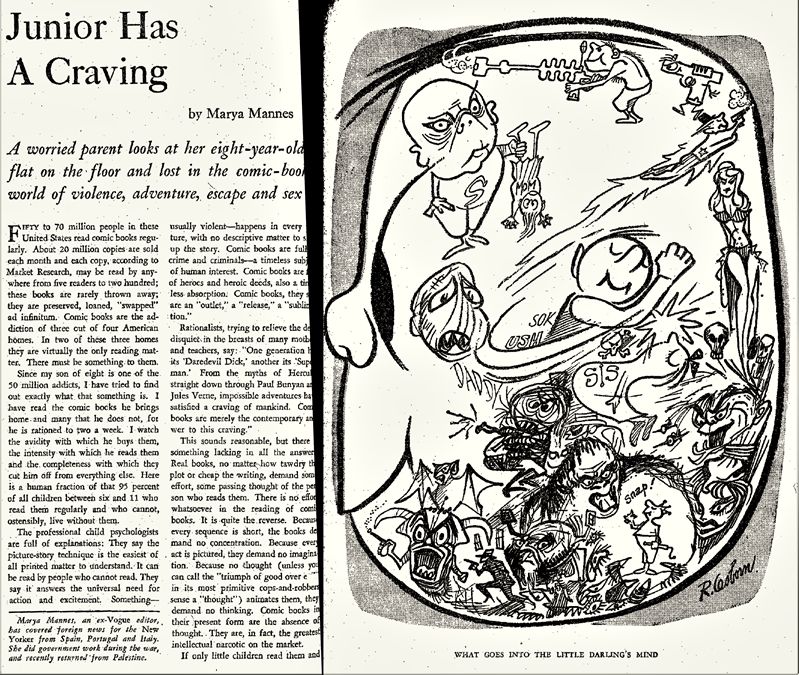

“Junior Has A Craving,” Marya Mannes, NEW REPUBLIC (Feb. 17, 1947)

Marya Mannes

“Though there is no palpable evidence to support the following statement,” observed Mannes in her article, “it is at least reasonable to assume that just as the childhood use of tobacco can stunt the growth of the body, so can the excessive reading of comics stunt the stature of the mind.” [“Junior Has A Craving,” Marya Mannes, NEW REPUBLIC, Feb. 17, 1947.]

Like many of comics’ detractors, Mannes didn’t let lack of scientific evidence stand in the way of her opinion.

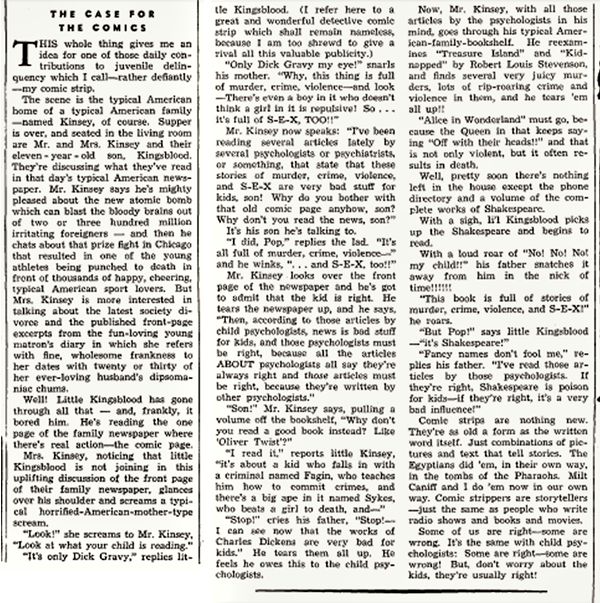

Capp skewered Brown and like-minded critics with a satirical scenario wherein a flustered father seeking to ban his son from reading comics. In typical Cappian fashion, he inserts the topically recognizable names “Kinsey” and “Kingsblood” to get a giggle by referencing two recent best-sellers regarding sex and social hypocrisy. His words were reprinted in the SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE as a rejoinder to Brown’s takedown in the same issue.

Al Capp on the day of the broadcast (March 2, 1948)

“The scene is the typical American home of a typical American family–named Kinsey, of course. Supper is over, and seated in the living room are Mr. and Mrs. Kinsey and their eleven-year-old son, Kingsblood. They’re discussing what they’ve read in that day’s typical American newspaper. Mr. Kinsey is mighty pleased about the new atomic bomb which can blast the bloody brains out of two or three hundred million irritating foreigners…”

“Well, Little Kingsblood has gone through all that–and frankly, it bored him. He’s reading the one page of the family newspaper where there’s real action–the comic page.”

“Mrs. Kinsey, noticing that little Kingsblood is not joining in the uplifting discussion of the front page of their family newspaper, glances over his shoulder and screams a typical horrified-American-mother-type scream.”

“‘Look!” she scream to Mr. Kinsey. ‘Look at what your child is reading.'”

“‘Alice in Wonderland’ must go,, because the Queen in that keeps saying ‘Off with their heads!!’ and that is not only violent, but it often results in death.”

“Well, pretty soon there’s nothing left in the house except the phone directory and a volume of the complete works of Shakespeare.”

“With a sigh, li’l Kingsblood picks up the Shakespeare and begins to read.”

“With a loud roar of ‘No! No! Not my child!’ his father snatches it away from him in the nick of time!!!!!!”

“‘This book is full of stories of murder, crime, violence, and S-E-X!’ he roars.”

“‘But, Pop!’ says little Kingsblood–it’s Shakespeare!'” [“The Case For The Comics,” Al Capp, SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, March 20, 1948.]

“The Case For The Comics,” Al Capp SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE (March 20, 1948)

After a bit more barbed repartee and posturing by the panelists, a microphone was passed among the audience for questions. It’s quickly evident that the audience had among its number several well-known cartoonists, well-spoken children and a strong showing of comic book defenders.

The first questioner was an unnamed woman from the CSAA who posed a query to Brown as did Charles Biro, editor of Lev Gleason Publications’ much reviled, CRIME DOES NOT PAY. Edwin Lukas, asked Mannes if she thought comics contributed to juvenile delinquency; a correlation she denied making.

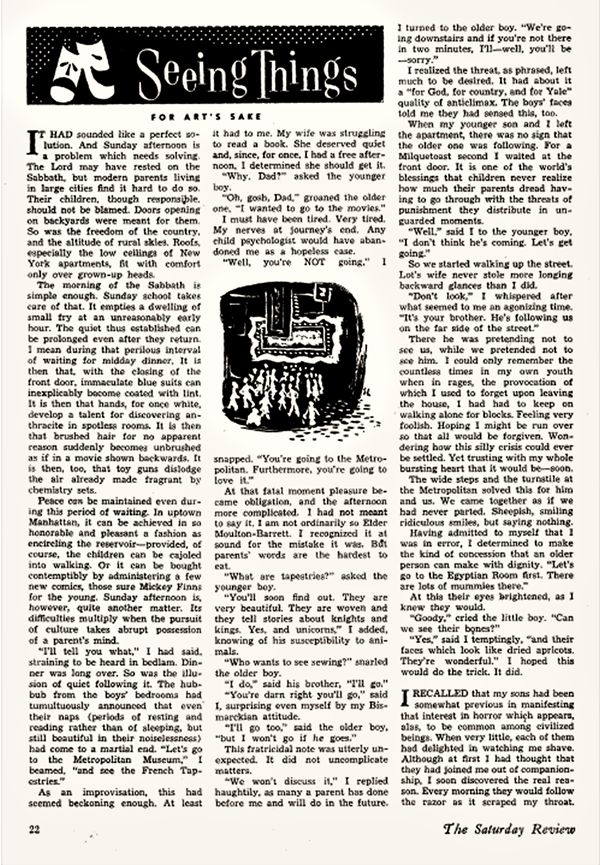

Frank’s turn came and she directed her question to Brown. She confronted him with a quote from a piece he wrote for his column, “Seeing Things,” in a recent issue of the SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE.

“For Art’s Sake,” by John Mason Brown SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE (Feb. 14, 1948)

“Mr. Brown, in the February 14th issue of the SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE you wrote a charming article on a little trip you took with your children, a cultural trip I believe, to a museum to show them a tapestry and found surprisingly, to you, that they were only interested in the murderous ones. And what you said, may I quote your words: ‘To the young, suffering is almost unimaginable, death is inconceivable. Pain is not real to them. Violence is. And this, quite naturally, they see as an expression of vigor, a manifestation of health and adventure.’ Now I would like to ask you, in view of the fact that in the hands of responsible comic publishers, this is what is done in the comics, how does it happen, in so short a time, you have changed your mind?”

Brown artfully sidesteps her question, denying that he had changed his mind, averring that he was always against the wholesale bloodlust of the comics.

Even though it was couched in pomposity, it was evident from this program that the level of opposition to comic books had entered a new phase. The comic book controversy had lingered in the background for years as other world events took precedence. Wertham’s first attacks were covered only in the New York City press, but this radio broadcast brought the arguments to the wider nationwide audience. And with a larger audience came a change in tone.

The earlier, relatively genteel arguments centering around the readability of comics had given way to a more serious, more urgent charge that they contributed to delinquent behavior. Bolstered by the supposed clinical evidence cited by Dr. Fredric Wertham, comics’ opponents sharpened their attacks.

Suspicious of such “evidence,” Ed Lukas looked to his own research. Lukas accompanied Frank to the “America’s Town Hall” broadcast and at first blush, he seemed to be an odd ally for her. As a criminologist and the head of an organization devoted to crime prevention, it figured Lukas would side with those who found an easy demon in comic books. However, he eschewed this convenient answer by assigning blame to a source that many didn’t want to hear. “The way to prevent crime is to prevent the criminal,” he had been quoted. “I have talked to hundreds of adult criminals and I don’t know of one who felt that when he was a child he was loved and wanted by his parents.” [Boyle, Hal, “Crime Cures,” April 10, 1948.]

Boyle, Hal “Crime Cures!,” (April 10, 1948)

In a March 3rd letter to Mannes following the America’s Town Meeting broadcast, Lukas painstakingly laid out his case in favor of comics by discussing the relevance of psychological “sublimation” (the change of a socially unacceptable behavior into a socially acceptable form) cited by Mannes in her 1947 article and his resulting conclusion.

“All of which brings me to the point of suggesting that in comics, children find outlets for their naturally aggressive tendencies,” Lukas wrote, “If you prefer to call that sublimation (it might also be called a form of expression) then I can’t imagine why you should consider it harmful; the sense in which you use the word might also be interpreted to mean that it is good for the child (as healthy sublimation always is). On the other hand, if your use of the word was intended to imply that it is harmful to sublimate in this way, then–as my question last night implied–I merely ask for proof which you may have (which all of us seem to lack) that reading comics has in itself produced any harmful emotional disturbances in children.” [Edwin Lukas letter to Marya Mannes, March 3, 1948.]

But the battle wouldn’t end with a well-reasoned letter. In fact, the battle was about to get far nastier.

In case you would like to hear the entire broadcast yourself, they are available on the “American Voices” website. Here is the link to the first part of the program:

and to the second part:

1 Comment ?>

You’re welcome, Wayne! It is well worth listening to the entire broadcast. A lot came out of this debate, as it essentially brought the comic book controversy to the entire country. Wertham didn’t become a national figure until after this. It basically set the stage.