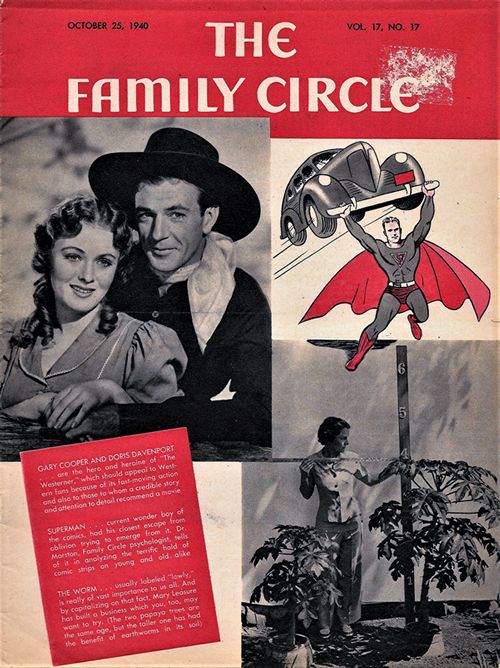

FAMILY CIRCE (Oct. 25, 1940)

©2019 Ken Quattro

Olive Byrne [aka “Olive Richard”]

“Olive Richard” was the pseudonym of Olive Byrne, who was one part of the triad forming the polyamorous arrangement Marston had with her and his legal wife, Elizabeth. For obvious reasons, this wasn’t a relationship that was publicly acknowledged, much less touted to the readership of a national weekly.So, while the clandestine nature of the relationship between interviewer and interviewee remained secret to the unsuspecting reader of 1940, it informs knowing historians when the article is read today.Ostensibly, the article is about Marston’s thoughts on the reaction of Americans who were panicked by the Oct. 30, 1938, “War of the Worlds” broadcast by Orson Welles and company. It seems a strange starting point for an interview, seeing as this issue of FAMILY CIRCLE came out two years later. No matter, Marston explained the supposed panic (which in itself was over-stated by newspapers) and he tied it to the comics.

“Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” pg. 1

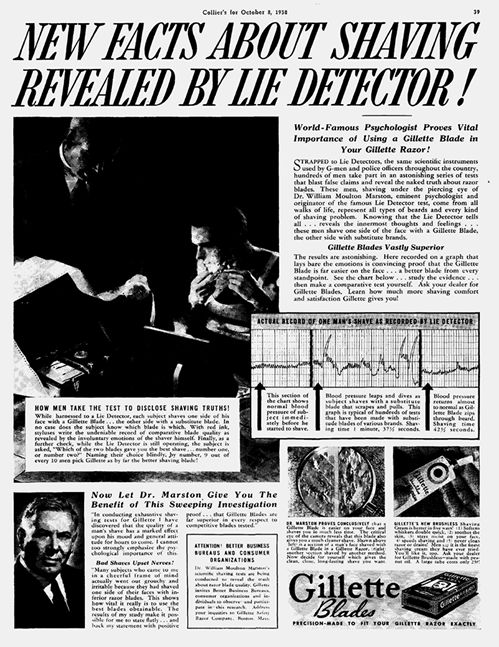

“This episode in American spoofology is attributable almost entirely to the comics.”“Comic-strip stories like ‘Buck Rogers,’ appearing in daily newspapers and Sunday comics sections, and recently in monthly comics magazines, have created a world of fantasy that is almost as real to adults as it is to children. And that means that sane grownups sometimes cannot tell the difference between fact and fancy. There are millions of normal men and women today who have no mental resistance at all to tales of the weirdly impossible. No supernatural being is too illogical to believe in. Orson Welles’ fascinating radio experiment proved that Americans today are living an imaginary mental life in a comics-created world!” [ Richard, Olive, “Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” FAMILY CIRCLE, Oct. 25, 1940.]Marston’s unsubstantiated conclusion may seem outlandish, but it came from a man who only a few years earlier made the news for claiming that there was a difference in the way women of varying hair colors fell in love. He also had conducted experiments with his lie detector for Gillette Razor Company that “proved” their razor blades gave a closer shave.

Gillette Razor Co. ad, COLLIER’S (Oct. 8, 1938)

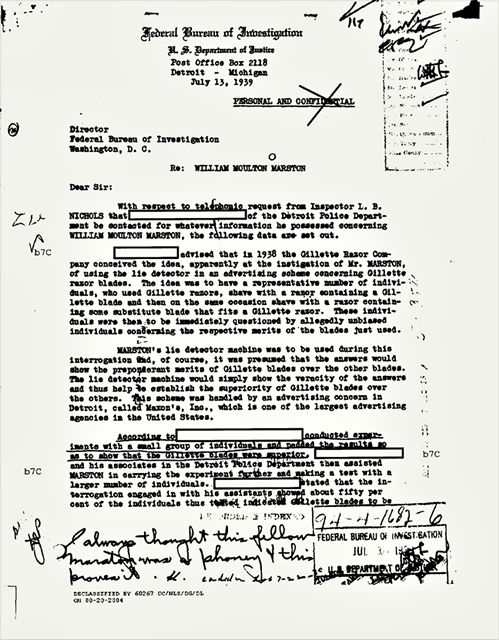

A Detroit Police Department inspector was suspicious of the veracity of these claims in the ads. Since the advertising agency for Gillette was headquartered in Detroit, it fell under his jurisdiction. He contacted the FBI for help with the investigation of both Marston and how the tests used in the ads were conducted. Their findings were contained in a one page memo to Director J. Edgar Hoover dated July 13, 1939.

“[Redacted name] advised that in 1938 the Gillette Razor Company conceived the idea, apparently at the instigation of Mr. MARSTON, of using the lie detector in an advertising scheme concerning Gillette razor blades. The idea was to have a representative number of individuals, who used Gillette razors, shave with a razor containing a Gillette blade and then on the same occasion shave with a razor containing some substitute blade that fits a Gillette razor.”

“MARSTON’s lie detector machine was to be used during this interrogation and, of course, it was presumed that the answers would show the preponderant merits of Gillette blades over the other blades. The lie detector machine would simply show the veracity of the answers and thus help to establish the superiority of Gillette blades over the others.” [“Re: William Moulton Marston,” FBI memo, July 13, 1939.]

Further testing was conducted by members of the Detroit Police Department along with Marston using a larger number of people in the test. This time, the positive reactions were evenly split between Gillette and the substitute razor blades. The conclusion was that Marston had faked his results to please his employers.

Director Hoover was blunt in his handwritten response to this information.

“I always thought this fellow Marston was a phoney & this proves it. — H.” [Ibid.]

“Re: William Moulton Marston,” FBI memo (July 13, 1939)

Despite his somewhat shaky reputation, Dr. Marston was a popular media source. Whenever an “expert” opinion was needed, Marston was ready and willing to give his. This was particularly true when it came to FAMILY CIRCLE, as he had been appearing in its pages since 1936. It didn’t hurt that one of his wives was usually his interviewer.

After made his initial comments tying the “War of the World’s” panic to comics, “Richard” went on to describe her own (and Martson’s) children read them. She noted how “parent-teacher groups, women’s clubs, and other parents’ organizations were starting to be a little worried over the possible harm such assiduous comics reading might do our future generations…”

“Stirling [sic] North, in The Chicago Daily News , added to the foment with his scathing indictment of the comics magazines. North pulled no punches when he said, ‘The lurid publications depend for the appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture, abduction, superman heroics, voluptuous females, blazing machine guns, and hooded justice.'”

“With terrible visions of Hitlerian justice in mind, I went to Dr. Marston, whose common-sense and farseeing views usually quiet the tempest in the teapot.” [Ibid.]

As “Richard” expected and predicted with her glowing lead–Dr. Marston was ready with the answers.

First, he dazzled “Richard” with a detailed accounting of how many comic book titles were published monthly, how many were sold each month and how many quarterlies added to that total. He also knew exactly the number of comics on average each child read and how many children read them. And of course, he also from memory, he was able to cite the yearly retail sales as being “between $14,000,000 and $15,000,000.” [Ibid.]

“When I professed amazement at the Doctor’s detailed knowledge of the subject,” wrote “Richard,” “he told me that he had been doing research in this field for more than a year–and that he had read almost every comics magazine published during that time!“ [Ibid.]

“Richard” made sure to emphasize that last line to ensure that the reader would be as amazed at the Doctor’s brilliance as had she.

After a few more statistics supporting the overall popularity of the comics medium, Marston claimed that “now the comics magazines have become their [children’s] weekday textbooks, and believe me, no youngster ever studied their schoolbooks as they do these new comics!” [Ibid.]

Instead of questioning the reality of that statement, “Richard” simply accepted it and asked, “How do you explain their appeal?” [Ibid.]

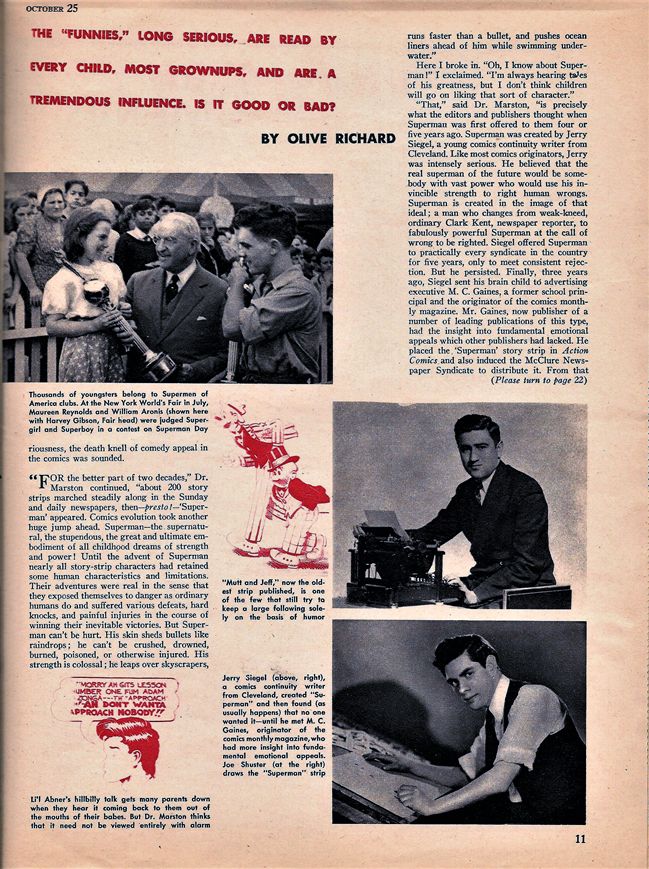

Marston’s answer involved a flawed overview of comic strip history (“Mutt and Jeff” wasn’t the first comic strip despite Marston’s declaration that it was) and attempted to show that such humor strips as “Popeye” and “The Gumps” had serious intent behind their humor.

“For the better part of two decades about 200 story strips marched steadily along in the Sunday and daily newspapers, then--presto!–‘Superman’ appeared. Comics took another huge jump ahead. Superman–the supernatural, the stupendous, the great and ultimate embodiment of all childhood dreams of strength and power! Until the advent of Superman nearly all story-strip characters had retained some human characteristics and limitations. Their adventures were real in the sense that they exposed themselves to danger as ordinary humans do and suffered various defeats, hard knocks, and painful injuries in the course of winning their inevitable victories. But Superman can’t be hurt. His skin shed bullets like raindrops’ he can’t be crushed, drowned, burned, poisoned, or otherwise injured. His strength is colossal; he leaps over skyscrapers, runs faster than a bullet, and pushes ocean liners ahead of him while swimming underwater.” [Ibid.]

Sounds like Dr. Marston was impressed by Superman.

“Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” pg. 2

Marston’s rapturous description of Superman read like a press release from DC’s public relations department. If his intention was to catch the eye of someone in power at that publisher in hopes of securing a position, it worked. Max C. Gaines saw the article.

The story has often been told, but briefly, Gaines (who was co-owner of All-American Publications, DC’s sister company) was unsurprisingly impressed by Marston’s enthusiasm for comic books and DC in particular. The two corresponded and eventually, Gaines hired Marston to create a character of his choosing. After some debate, so the story goes, Marston’s wife Elizabeth suggested a female super-hero. Enter Wonder Woman.

“Richard” tried to put the thought process behind Marston’s Superman glorification into one sentence.

“‘You mean Superman fulfills children’s wishes, and that is whey they like the comics magazines? I asked Dr. Marston, ‘Everybody has always said it was story value–the primitive thrill of danger and adventure.'”

“‘Everyone has always said that,’ the Doctor agreed, ‘and everybody has been wrong. The ‘Superman’ continuities have almost no story value at all; they are nearly 100% wish-fulfillment pictures. What they gratify are the strongest human desires in life: The wish for strength and power, and the wish to benefit other people.'” [Ibid.]

“‘Jerry Siegel’s comics idea was far more radical than he himself realized. He forgot plot, danger, menace, and all suspense; he omitted all human qualities in his hero with which readers are supposed to identify themselves. His story is no story at all but simply a picturing of what readers would like to be and to do.” [Ibid.]

In an effort to fit Jerry Siegel’s writing style into his hypothesis, Marston denied the writer virtually every attribute that makes a writer. As Marston described him, Siegel did little more than suggest to the artist what action scene should happen in each panel; storyline and character development be damned. Nonetheless, “Richard” was convinced.

“‘Well,’ I admitted, ‘you’ve sold me on that one. But what about other comics? Some of them are full of torture, kidnapping, sadism, and other cruel business.'”

“‘Unfortunately, that is true,’ the Doctor agreed. ‘But there are one or two rules of thumb which are useful in distinguishing sadism from exciting adventure in comics. Threat of torture is harmless, but if the torture itself is shown in the strip, it becomes sadism. When a lovely heroine is bound to the stake, comics followers are sure that rescue will arrive in the nick of time. The reader’s wish is to save the girl, not to see her suffer. A bound or chained person does not suffer even embarrassment in the comics, and the reader, therefore, is not being taught how to suffer.” [Ibid.]

“Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” pg. 3

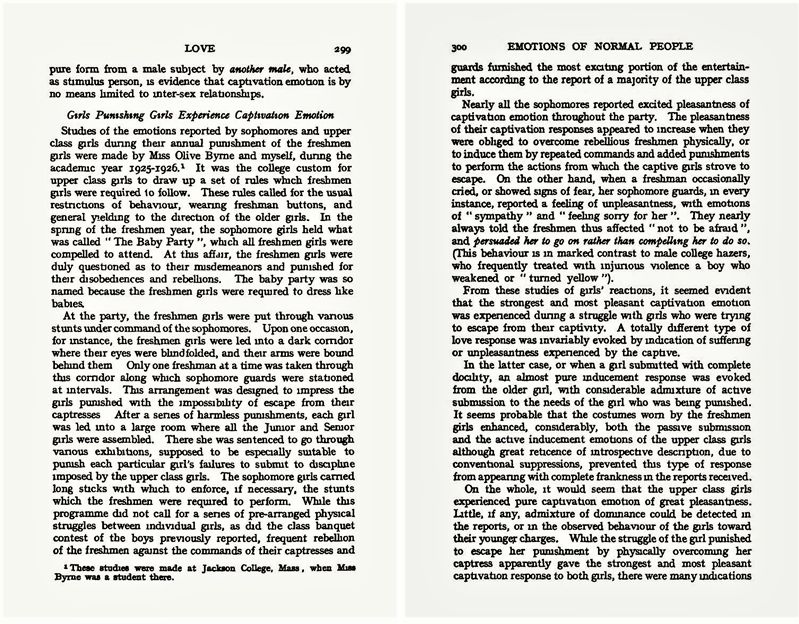

The average reader of 1940 likely hadn’t read Marston’s 1928 psychology text, EMOTIONS OF NORMAL PEOPLE. If they had, they may have read his above words with a bit of skepticism.

In this book, Marston attempted to demonstrate that certain behaviors deemed aberrant by then-current society, were anything but abnormal. One specific chapter dealt with an experiment conducted by Marston and his then student, Olive Byrne, which involved their witnessing a “Baby Party” conducted at Jackson College in Massachusetts.

“At this affair, the freshman girls were duly questioned as to their misdemeanors and punished for the disobedience and rebellions. The baby party was so named because the freshman girls were required to dress like babies.”

“At the party, the freshman girls were put through various stunts under the command of sophomores. Upon one occasion, for instance, the freshman girls were led into a dark corridor where their eyes were blindfolded, and their arms were bound behind them.”

“Nearly all the sophomores reported excited pleasantness of captivation emotion throughout the party. The pleasantness of their captivation responses appeared to increase when they were obliged to overcome rebellious freshman physically, or to induce them by repeated commands and added punishments to perform actions from which the captive girls strove to escape. [EMOTIONS OF NORMAL PEOPLE, William Moulton Marston, pgs. 299-300. 1928.]

EMOTIONS OF NORMAL PEOPLE, pgs. 299-300 (1928)

Marston continues on to assuage “Richard’s” worry about the bad influences comics may have upon the “young of America.” Using the example of a “Li’l Abner” strip, he assures “Richard” that the “hillbilly language” was “‘grotesque enough to be amusing, whereas gangster argot is not.'”

“‘If the comics do so much good,’ I said, ‘isn’t there some danger that all young America will forget the classics simply because they aren’t printed on rough paper with glaring illustrations?'”

“‘I used to think a lot about that angle myself,’ the Doctor admitted, ‘but recently the Detective Comics group instituted an excellent feature. In a letter to juvenile readers Superman says, ‘You need an agile, quick-thinking mind as well as physical perfection. One of the important means of cultivating your mind is to read good books. Each issue of these magazines contains a book review with a suggestion that if you like the review you go to the library, get the book, and thus get into the habit of reading at least one good book a month.'” [“Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” op. cit.]

The irony of this statement wouldn’t be obvious to anyone, not even Marston, for several years. The book reviewer for Detective Comics (DC) that Marston was lauding, was Josette Frank. Over time, after Marston had been hired to write Wonder Woman, Frank would be his most virulent in-house critic, among other things, deploring “the fact that the ‘ladies’ in this strip [Wonder Woman] always seem to appear in chains or irons–whatever you would call them–and this might perhaps come under the head of sadism.” [Josette Frank letter to Harry Childs, Feb. 8, 1943.]

The interview winds to its end with Marston sagely answering “Richard’s” final question about parents could do about bad comics.

“Children are not so dumb or unintelligent as we suppose them to be. They want triumph and glory without paying the price of pain, and the comics magazines that fail to give them what they want will be discarded.” [“Don’t Laugh At The Comics,” op. cit.]