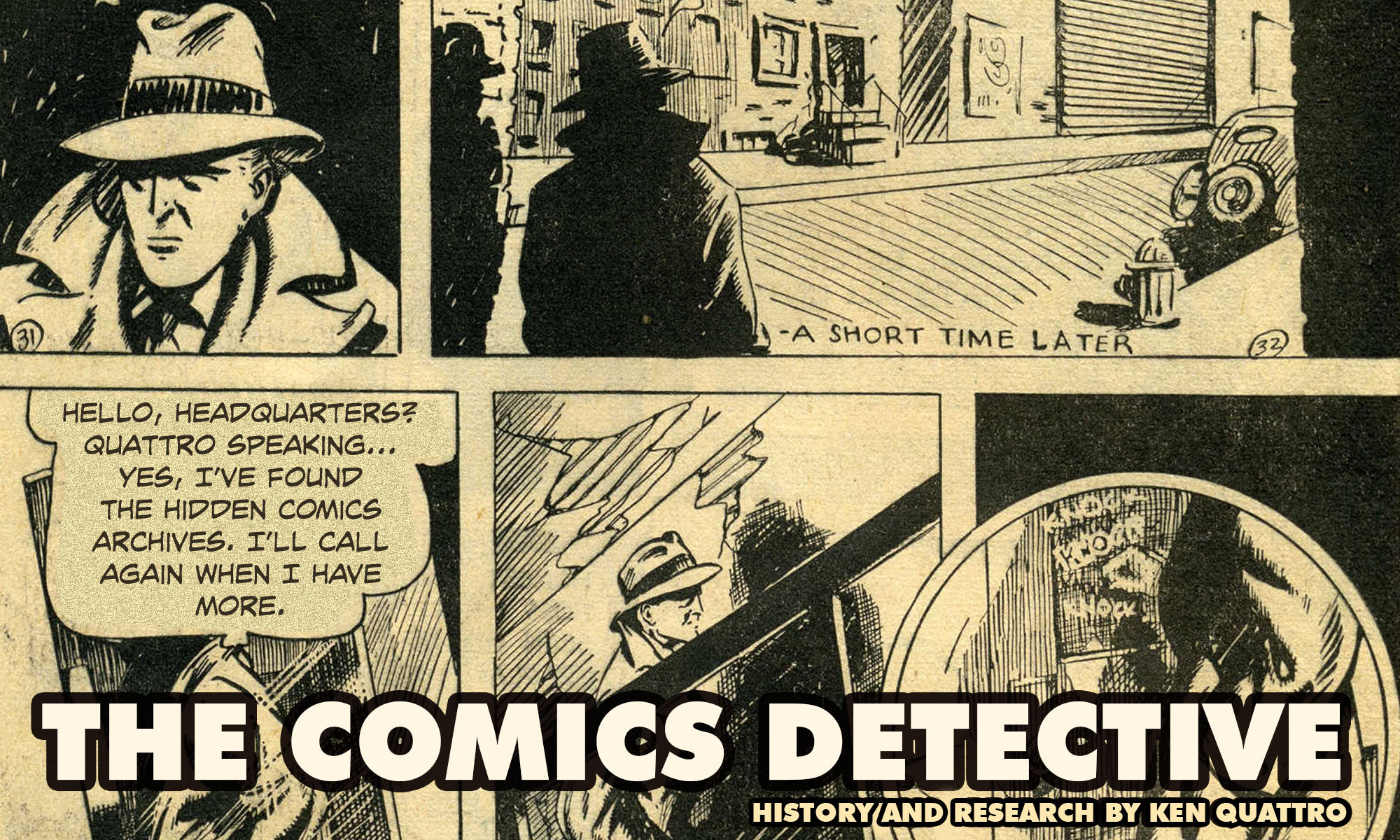

MARVEL STORIES vol. 2 #2 (Nov. 1940) and FANTASTIC FOUR #1 (Nov. 1961)

Some years back, I first wrote this partially tongue-in-cheek article as a response to one of the most enduring arguments among comic book fans and historians, “Who was most responsible for the creation of the Fantastic Four?” Like everyone else who wasn’t in the room with Jack Kirby and Stan Lee–I can’t say for certain. But that hasn’t ended the debate and while it rages on, I looked back, way back, to see if there was a possible antecedent that may have influenced either, or even both, of these creators. And I may have found one.

©2019 Ken Quattro

How do you determine the germ of an idea?

There has been much gnashing of teeth, vituperative prose and verbal bloodshed over who should get credit for the creation of the Fantastic Four.

Jack Kirby fans are steadfast in their belief that their man brought the concept to Stan. Kirby had, after all, just finished a run on the Challengers of the Unknown for DC. In their eyes, Ace, Prof, Rocky and Red had just been reimagined as Ben, Reed, Johnny and Sue.

Stan Lee, however, saw it differently. His story was that Timely-Atlas (Magazine Management) publisher Martin Goodman had noticed that National’s (DC) JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA comic was selling particularly well. He then ordered Stan to create a super team to headline a new comic for their company.

“I would create a team of superheroes if that was what the marketplace required,” Lee wrote in ORIGINS OF MARVEL COMICS,“But it would be a team such as comicdom had never known. For just this once, I would do the type of story I myself would enjoy reading if I were a comic-book reader.”

Lee’s words were red meat to Kirby fans. Personal biases aside, perhaps there is some truth to both versions.

And perhaps there is a third person deserving of credit as well.

John L. Chapman.

“If momentary exposure to the cosmic rays beyond the Heaviside Layer made a super-man of an ordinary mortal–what fabulous titan of strength and intelligence might the human become who’d spend hours under such forces!”

So reads the blurb accompanying the short story, “Cycle”, by the above mentioned Mr. Chapman in MARVEL STORIES vol. 2 #2 dated Nov. 1940.

Originally from Gilby, ND, John Leslie Chapman was born May 21, 1920, the son of a telegraph operator. The Chapmans had moved to Minneapolis by John’s high school years and around that time, young John, apparently a science fiction fan, eventually became a member of the fledgling Minneapolis Fantasy Society. This group boasted future Science Fiction of America Grand Master, Clifford D. Simak, as its director. Chapman went on to the University of Minnesota, gaining a degree in journalism.

Chapman had only a relative few number of science fiction stories published and most of those came in at the very end of the 1930s and into the early 1940s. One short story he wrote for COMET vol. 1 #1 (Dec. 1940), entitled, “In the Earth’s Shadow,” featured an escaped convict who steals fuel from a rocket refueling station. The villain has the suspiciously familiar-sounding surname of “Siegal.”

Like most able-bodied young men of the time, with America’s entry into WWII, he served in the military. Specifically, with a bomber squadron stationed in Burma and China. At war’s end, he came back to Minnesota and got a job at the MINNEAPOLIS STAR AND TRIBUNE, perhaps aided by his connection to Simak, who was an editor on the newspaper.

Chapman, too, became an editorial writer for the paper, before moving on to Convair, an aircraft manufacturing firm in San Diego. While working as an engineering writer for that company, he began freelancing as a science writer for various publications. In 1962, he won first prize for his article, “The Uncanny World of Plasma Physics,” that appeared in the October 1961 issue of HARPER’S. He beat out Arthur C. Clarke, who only got an honorable mention.

Chapman’s rather unremarkable career as a science fiction writer likely wouldn’t even be under consideration if it were not for this barely six-page effort that bears some interesting similarities to the origin of an iconic comic book team some 21 years hence.

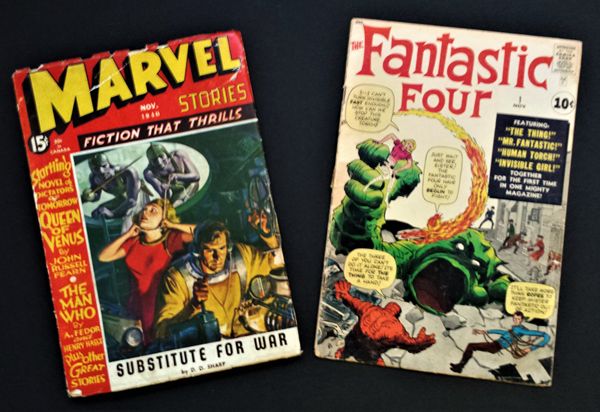

“Cycle” by John L. Chapman; illustration by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby

“Cycle” was the story of a man named Drake, who had been sent in a rocket on a trip to the moon, the “first man to leave the earth’s atmosphere.” Suddenly,the “jets” on his ship misfired, “in the vicinity of the Heaviside Layer,” and he began plummeting back toward the ground.

Apparently, upon reaching this point, Drake was exposed to cosmic radiation.

“At first he thought it was the weightlessness of deceleration. But as the minutes fled by, and the ship’s velocity decreased steadily, the certainty of a change became more prominent in Drake’s mind.”

Drake survives the crash and is subsequently brought to the World Tower and into the presence of the Western Hemisphere’s dictator, Michael Gurth.

“‘Tell me,’ said Gurth, ‘Did Drake pass the Heaviside Layer?'”

“Tinsley scoffed. ‘I’ve no time for absurd questions–“

“‘Then he did pass the Heaviside Layer.'”

“‘I don’t know. Judging from his velocity and the time that telescopes were able to follow him, I should say yes. but it has no bearing on the matter. Drake fell somewhere near the coastline. That we know. Unless he was superhuman, he couldn’t have survived.'”

“‘Perhaps,’ said Michael Gurth with a slow smile, ‘he was superhuman.'”

Gurth may have been a despicable despot, but he also was also well-versed on the accepted science of the time–courtesy of writer Chapman.

The Heaviside Layer, more properly referred to as the Kennelly–Heaviside layer for its co-discoverers, is a layer of ionized gas some 56 to 93 miles above the Earth’s surface. A prosaic definition, to be sure. But in the era that Chapman wrote “Cycle,” it was described with a bit more charm:

“The upper layer of the Stratosphere in the daytime becomes the home of the Heaviside layer–the invisible, intangible vault of the sky on which the radio waves can echo, rebound, and so go round the earth carrying broadcasts, which otherwise would rush straight off into unreceptive, echoless, interstellar space.” [Heard, Gerald, EXPLORING THE STRATOSPHERE, pg. 28. (1936.)]

“The body and build was [sic] perfect. A wide chest tapered from broad shoulders. The hands were huge and strong. The legs were long and muscular. The hair looked as though it might have been dark at one time. Now it possessed a golden luster, matching the slitted [sic] gray eyes whose piercing gaze sent a chill down Tinsley’s spine. Never before had the little scientist seen such masculine beauty.”

Overlooking the purple prose and homoerotic undertones, what Chapman was describing was Drake’s transformation into a super human.

“Drake was the first man to pass the Heaviside Layer, the first human being to meet with the utter unknown. He was exposed to the natural cosmic ray forces, the same forces that the Heaviside Layer prevents from reaching the earth. You recall, Dr. Tinsley, an age-old theory of evolution concerning cosmic rays? The life forces they were called, the origin of the animate impulses. Yes–you begin to comprehend, don’t you? You understand now what has happened to Drake. He was been exposed to naked cosmic rays, and as a result he was super-evolved.”

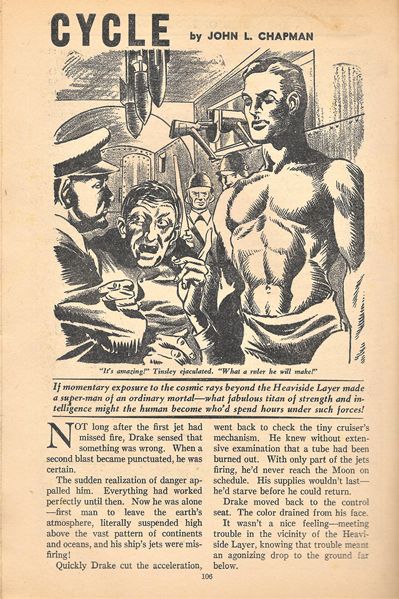

At first reading, this long-winded explanation seems implausibly silly; typical early science fiction science. But a little research reveals that Chapman had done his homework before writing this story.

Excerpt from “Secrets of Life Sought in Mystery Ray,” POPULAR MECHANICS (Oct. 1930)

“Within the last three years, it has been discovered that invisible rays, similar to those which help to cure cancer, supply the motive power in creating new forms of life. And as the evidence piles up, the daring theory is being advanced that X-rays, radium rays and cosmic rays are among the primary causes of evolution–if they do not happen to be the sole cause.” [“Secrets of Life Sought in Mystery Ray,” POPULAR MECHANICS, pg. 564. (Oct. 1930.)]

Gurth’s realization that it was the cosmic rays which gave Drake his super-powers sets the stage for the dictator’s own trip into space to be exposed to the cosmic radiation himself in order to, “…be gifted with unlimited power and military prowess that would enable me to dwarf the Eastern Hemisphere in a matter of weeks!”

I won’t spoil the ending in case you wish to seek out this story, but needless to say, it doesn’t work out as Gurth imagines.

So how does this all tie into the Fantastic Four’s origin?

If somehow you don’t know the story, Dr. Reed Richards is planning a rocket trip into space, but his pal, pilot Ben Grimm, angrily confronts Reed with his concerns about space travel:

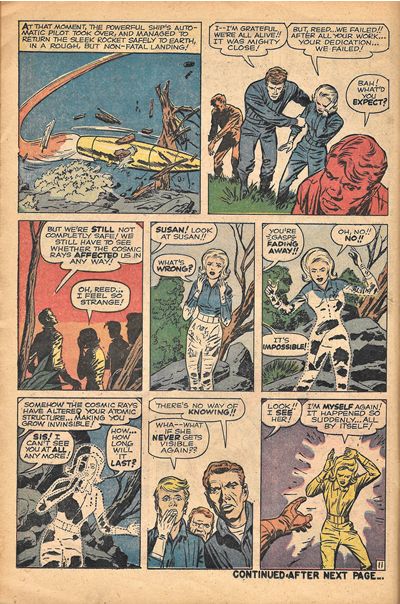

FANTASTIC FOUR #1, pg. 10

pg. 11

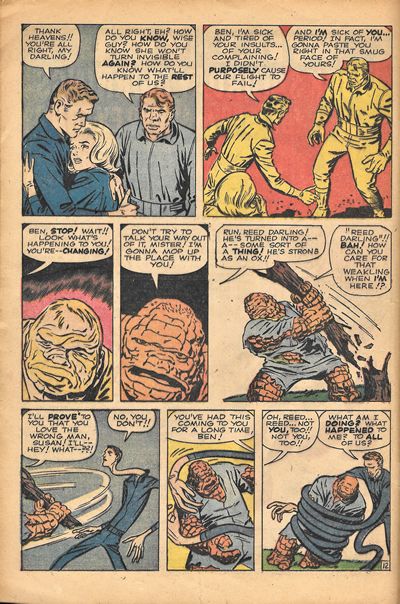

pg. 12

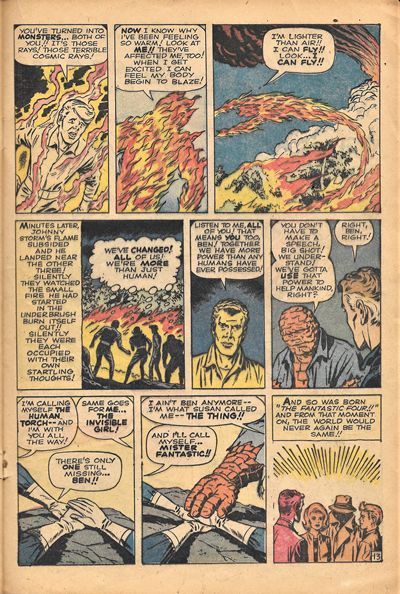

pg. 13

Coincidence? Maybe, but consider this: Both creators of the Fantastic Four were around and likely aware of Chapman’s “Cycle” story.

Stanley Lieber (Lee) was on the premises at Timely in 1940, “assisting.” It is a fair assumption that he read that issue of MARVEL STORIES when it came out and perhaps it was a latent memory of it that he grafted onto Kirby’s Challengers concept. It’s even possible that Lee pulled copies of the Goodman pulps upon occasion for “inspiration.”

And Kirby? Just look to the bottom of the MARVEL STORIES contents page: “INSIDE STORY ILLUSTRATIONS…by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby” All of the illustrations in this pulp, including the one for “Cycle,” were drawn by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

Though the “cosmic radiation” twist was probably Lee’s contribution (consider the role of radiation in other Marvel heroes origins–be it cosmic, gamma or spider-borne), Kirby likely read “Cycle”, as well.

All that I’ve proposed is conjecture, obviously. What Kirby and Lee were creating in 1961 was just a comic book–not a cultural icon. They were looking at producing a saleable comic and the hook they came up with–cosmic radiation created superheroes–may have just been conceived from out of thin air. Somewhere in the Heaviside Layer.

BUT WAIT! Check out my next post for a related bonus featurette!