Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson and family (1923)

©2019 Ken Quattro

The details were purposely oblique, in keeping with military protocol.

“…now at the Hotel Astor is Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, who was in command of the mounted detachment of the A.E. In G., who will go from New York to Washington to ask for a leave while he returns to Sweden for his wife, who has a Swedish lady of title, when they will return to this country.” [ARMY AND NAVY REGISTER, Feb. 12, 1921.]

The army had reassigned Malcolm to Camp Dix in Hoboken, New Jersey and he was desperately trying to get back to his new bride waiting for him in Sweden. He had been replaced as commander of the Mounted Detachment on January 1, 1921 after being removed several months earlier in October 1920.

Not only had Wheeler-Nicholson suffered the humiliation of losing a command, he had been moved from Class A to Class B in the ranking system used by the U.S. Army to determine promotions. The move carried with it not only a reduced chance of promotion, but the very real threat of outright dismissal from the service.

The specific law creating the two-class promotion system had been created by the U.S. Congress in 1920 and was seen as a way of reducing the size of the standing army during peacetime by weeding out undesirable officers.

“Sec. 24a. PROMOTION LIST.–For the purpose of establishing a more uniform system for the promotion of officers, based on equity, merit, and the interests of the Army as a whole, the Secretary of War shall cause to be prepared a promotion list, on which…the names on the list shall be arranged, in general, so that the first name on the list shall be that of the officer having the longest commissioned service; the second name that of the officer having the next longest commissioned service, and so on.”

“…persons appointed as lieutenant colonels or majors under the provisions of section 24 hereof, shall be placed immediately below all officers of the Regular Army who, on July 1, 1920, are promoted to those grades retrospectively under the provisions of section 24 hereof: Provided, That the board charged with the preparation of the promotion list may in its discretion, assign to any such officer a position on the list higher than that to which he would otherwise be entitled, but not such as to place him above any officer of greater age, who commissioned service commenced prior to April 6, 1917.” [Statutes of the United States of America Passed at the Second Session of the Sixty-Sixth Congress, 1919-1920, Part 2, pg. 772-773 (1920)]

The statute was controversial within the ranks of the Army, particularly to those officers whose promotions came after the United States entered the Great War on April 6, 1917, as had Malcolm’s promotion to Major.

“Sec. 24b. CLASSIFICATION OF OFFICERS—Immediately upon the passage of this Act, and in September of 1921 and every year thereafter…a board of not less than five general officers, which shall arrange all officers in two classes, namely: Class A, consisting of officers who should be retained in the service, and Class B, of officers who should not be retained in the service.” [Ibid. pg. 773.]

This was the portion of the statute which scared Wheeler-Nicholson the most. Beyond the indignity of being put onto a list of unwanted officers and losing a chance at promotion, there was a real possibility that he would be dismissed from the Army entirely. Making matters worse was the fact that such dismissed officers would only received a monthly pension of 75% of their working pay, or about $35.

Wheeler-Nicholson didn’t take his placement into Class B lying down. He reportedly protested his assignment to the list, charging that he had been unfairly singled out by Gen. Fred Sladen, the ranking officer overseeing the Class B rankings, who only knew Malcolm from his current evaluation scores. Other officers in similar jeopardy quietly supported Malcolm’s protest. But he was the only one willing to go public with his complaints.

As always, Malcolm had the support of his mother. In late December 1920, several months after her son had been removed from his command, she boarded a ship to Europe to be with Malcolm and Elsa. It a typical bit of Antoinette-sourced hyperbole, a Portland newspaper article noted that “Major Nicholson is commander-in-chief of the artillery of the American forces in Germany.” [“Reed Alumni to Get Together on Next Wednesday,” OREGON SUNDAY JOURNAL, Dec. 26, 1920.]

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (Dec. 26, 1920)

Despite her proclivity for exaggeration, Antoinette maintained powerful friends in many places. The same article noted that she would be visiting with Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt prior to heading to Europe. Antoinette chaired the Oregon Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association, dedicated to building a center in the recently deceased President’s name in Portland and had a close relationship with the Roosevelt family. She also fostered relationships within Oregon’s political establishment and as they had done previously in assisting Malcolm’s entry into St. John’s and the U.S. Army, one of the state’s Senators stepped up to help him with his demotion to Class B.

Malcolm upped the ante by not only going public with his protests, but by also asking the Army to court martial the ranking officers who placed him into Class B.

“…Maj. Wheeler-Nicholson charges that although he has been rated exceptionally high as an officer by most of his commanders, those in the War Department who have handled his case have disregarded those notations and have accepted the judgment of three of his commanders who disapproved of him. He also filed charges against Brig. Gen Frederick W. Sladen for false official statement—namely, that the former [Wheeler-Nicholson] was below average in command of a unit.” [“Method of Rating Efficiency Scored,” EVENING STAR, Aug. 10, 1921.]

WASHINGTON, D.C. EVENING STAR (Aug. 10, 1921)

Needless to say, this was a stunning charge and a huge risk to take. A junior officer rarely questioned, let alone publicly questioned, the decisions of a senior officer. The article goes on to detail that one of the reasons for Malcolm’s Class B status were the efforts being made on his part by some influential politicians.

“One of the principal charges against Maj. Wheeler-Nicholson, it appears from his brief, is that he went into debt. He explains that he incurred a debt of $4,000 after his parents had lost their property, by going to their aid, and educating a younger brother, while he was a lieutenant.”

“In his home state, Washington [sic], the circumstances of his debt were regarded as rather an honor to him, it is stated, but when the circumstances were brought to the attention of the War Department by Senator Poindexter and former Senators Chamberlain and Bourne, another black mark was put against his record on the ground that he had attempted to use ‘political influence.’” [Ibid.]

Several noteworthy details jump out of these paragraphs. One is the surprising financial state of his parents, who seemingly maintained an up-scale lifestyle. Another is the intervention of Senator Miles Poindexter from Washington, Oregon’s neighboring state.

Senator Poindexter was a Republican, as were many of Antoinette’s close circle of friends, who was born in Tennessee, but raised in Virginia and educated at a private school in Rockbridge County. The very same county Antoinette had recently claimed was where her father had been born. A small fabrication meant to development a potentially helpful relationship, perhaps?

Malcolm pulled no punches in his public attacks on Sladen and the officers who had rated his performance poorly.

“Basing an officer’s discharge from the Army on the so-called efficiency record kept of him by the War Department,” he stated, “might be likened in civil life to basing the discharge of an executive in an industrial concern on the sole testimony of an old lady in the village sewing circle.” [Ibid.]

The target of Malcolm’s wrath, Brig. Gen. Fred W. Sladen, was highly respected within the ranks of the Army. His father, Joseph, had won the Congressional Medal of Honor during the Civil War and Fred himself was the recipient of the Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Service Cross and France’s Croix de Guerre, with Palm for his service related to the Second Battle of the Marne in 1918. Previously, he had also served in the Spanish-American War and the Philippines Insurrection.

Sladen was viewed by his peers as a tough disciplinarian, a “soldier’s soldier,” with a commanding presence, leading one officer who had served under him to write: “The best-dressed officer I had ever seen was Gen.Fred W. Sladen, the Superintendent of West Point during my last three years there. His uniforms were perfectly fitted and always freshly pressed, with brass and leather buffed and shined to a high gloss. He moved in a precise, unhurried manner. The visual impact of his professional posture inspired instant respect.” [Newman, Major Gen. A. S., “Your Professional Posture Can Help Or Hurt You,” ARMY, vol. 23 #2, (Feb. 1973.)]

Apparently, Wheeler-Nicholson was not so impressed.

Malcolm’s strategy had initial success. On August 11, 1921, he was “notified that the matter has been postponed indefinitely. The reason for this action is not explained.” [“Maj. Nicholson’s Case Postponed,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Aug. 11, 1921.]

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (Aug. 11, 1921)

Wheeler-Nicholson had no doubt as to why his case had been put off.

“It may be that these bureaucratic old fellows are a little alarmed about some of the exposures that have appeared in the press,” he said, “I don’t know, and I have no idea when further action will be had. However my case goes,the thing is not ended. I am going right ahead to set my record right and make proof of the justice of my case, so no stigma will rest upon me in the minds of reasonable men.”

“I cannot tell what action, if any, will be taken on charges I have filed against General Frederick Sladen, also of Portland, for false statements concerning an official record. They may be dropped in the waste basket because of being filed by an inferior officer. If the law is followed they will be referred to the inspector general for investigation.”

“General Sladen represents Prussianism in the American army. He is cold and one of the kind that makes the army unpopular. His eyes are fixed on discipline and the tactics of Von der Goltz.”

“Why had he [Sladen] persecuted me? Possibly because I refused to prefer charges against my lieutenant adjutant as he desired, when I was commanding a cavalry squadron under him in the Coblenz district; perhaps because I went over his head to General Allen, commander-in-chief in Germany; perhaps his attitude as an artillery officer as compared with my attitude as a cavalry officer trying to build up the spirit of my men in humanitarian ways, instead of driving them.” [Ibid.]

Malcolm’s blistering attack on Gen. Sladen didn’t end his assessments of his superior officers.

“I have also filed against Brigadier General C. J. Bailey, who, under this army system, is a member not only of the board which originally placed me in class B, but is a member of the final board, the same board that renders final judgment. I charge him with false official statements and persecution. He is known for his mania for pursuing persons for whom he has conceived dislike.” [Ibid.]

Such attacks were virtually unprecedented, especially as they were made in the civilian press. Wheeler-Nicholson’s words resonated with other returned service men who also resented the strictness of the U.S. army of the era. Conscripted soldiers, who had been plucked from their civilian lives to fill the army’s ranks, were not used to such autocratic discipline. And there was a reciprocating resentment by West Point graduated officers to those who entered the service via civilian recruitment and privileged military schools, as had Malcolm. Wheeler-Nicholson wasn’t the only one to feel that disdain. Future President Harry S. Truman had a long-standing grudge against West Pointers for the way they had treated him when he, too, became an officer who achieved his commission straight out of civilian life.

Malcolm seemed to have won vindication, when a week later, President Warren G. Harding signed an executive order overturning the statute under which Class B had been created.

“Owing to defects in the procedure which led to the promulgation thereof and which rendered it invalid and void, the executive order of June 20, 1921, approving the action of the final classification board in proceedings under 23 B, act of June 4, 1920, finally classifying Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson, cavalry, in class B, is hereby rescinded and vacated and Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson is hereby restored to class A.” [“Nicholson is Restored to Class A,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Aug. 19, 1921.]

The article further stated that new rules governing the classification system were being considered in the wake of his complaints and that the Congress would hold hearing in its Fall session regarding them.

His battle apparently won, Malcolm was assigned to the Third Cavalry at Camp Ethan Allen in Vermont, where he awaited his wife, new baby and his mother, Antoinette, who had also followed him back from Europe, to Washington, D.C. while he fought his classification ranking.

There was a set-back when Acting Judge Advocate General Hull refused the court martial of Gen. Sladen. The decision for not putting Sladen on trial revealed some of the previously confidential reports that Sladen had written regarding Wheeler-Nicholson.

“Below the average,” Sladen wrote, “A man of good bearing and appearance, an egotistical, plausible talker, but very inaccurate and unreliable in his statement, especially as to himself…Nicholson lacked judgment and was unfitted for independent command.” [“Army Judge Refuses to Try Sladen,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Oct. 24, 1921.]

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (Oct. 24, 1921)

This damning characterization of Malcolm by Sladen was ruled by Hull to be “an expression of opinion, not statement of facts…and whether his opinion is accurate is not a question triable by court martial. If malice were shown, a superior officer could be brought to account for matter contained in such content, the decision says, but no malice on Sladen’s part is shown.” [Ibid.]

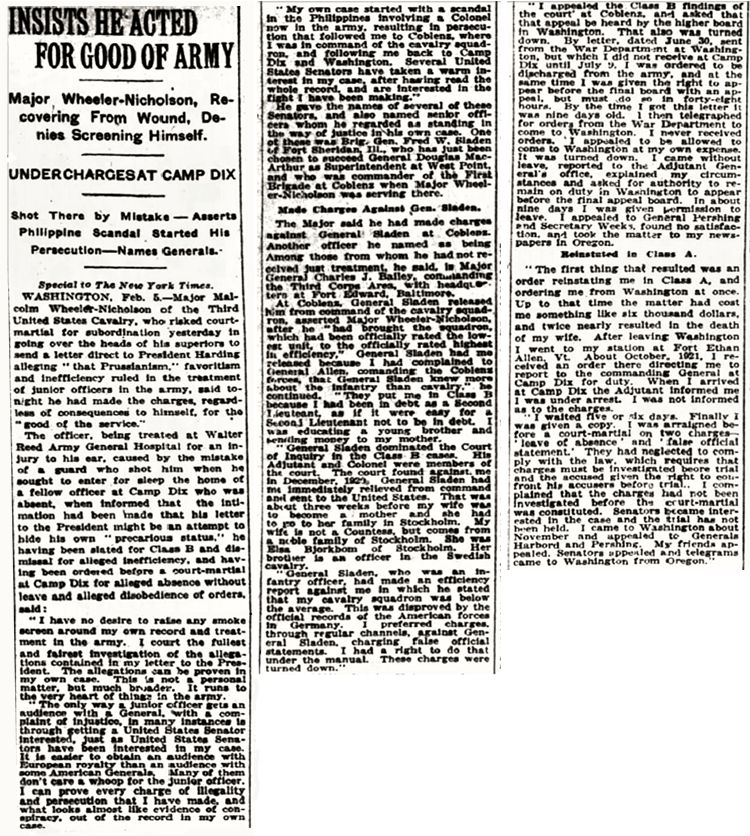

Not the outcome Malcolm had hoped for, but as he had been reassigned to Class A, he could continue to pursue his military career. However, Wheeler-Nicholson wasn’t satisfied. On Feb. 4, 1922, he wrote a letter to President Harding outlining his charges against the entire U.S. Army establishment.

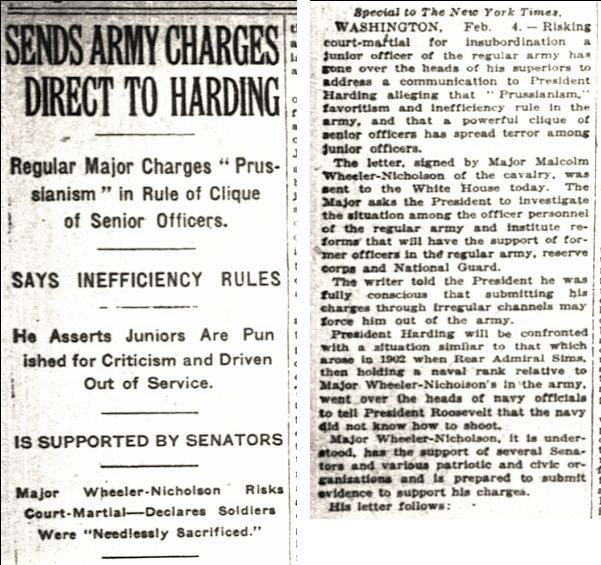

NEW YORK TIMES (Feb. 5, 1922)

“Risking court-martial for insubordination a junior officer of the regular army has gone over the heads of his superiors to address a communication to President Harding alleging that ‘Prussianism,’ favoritism and inefficiency rule in the army, and that a powerful clique of senior officers has spread terror among junior officers.”

“The letter, signed by Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson of the cavalry, was sent to the White House today. The Major asks the President to investigate the situation among the officer personnel of the regular army and institute reforms that will have the support of former officers in the regular army, reserve corps and National Guard.”

“The writer told the President he was fully conscious that submitting his charges through irregular channels may force him out of the army.” [“Sends Army Charges Direct to Harding,” NEW YORK TIMES, Feb. 5, 1922.]

If Malcolm’s previous public airing of grievances was risky, this was far more so. Even though his earlier charges against Sladen and the Class B system went public, at least he made them through the established chain of command. By going over the head of not only everyone in the Army, but the War Department and the Secretary of War, Malcolm had taken the ultimate gamble that the bad publicity would force Harding to act.

Wheeler-Nicholson’s letter to Pres. Harding, NEW YORK TIMES (Feb. 5, 1922)

“The army is suffering from a reign of Prussianism. The better type of officers are leaving the service. Protest and criticism are punished by every conceivable form of injustice and illegality. Juniors are openly persecuted. Seniors are not only protected in wrongdoing but are rewarded for oppressing their juniors. The Prussian type of officer is assured of advance, the liberal minded officer is slighted. Anglo-Saxon ideals of justice and fair play are being rapidly replaced by traditions foreign to the American nation. Justice is not only perverted and denied, but the laws are openly flouted.” [Ibid.]

Wheeler-Nicholson had to know that when he coined the word “Prussianism,” it would trigger a response. Not only would it convey the image of unbending martinets leading American troops, it would also be a sharp insult to the professional military men who had just helped defeat that hated German foe. An equivalent in later years would be the army of Eisenhower and MacArthur likened to Nazis.

“A veritable reign of terror exists among the junior officers of the army today. This is caused by the unhindered power of the clique to have any officer discharged from the service by operation of what is known as the Class B law. The scandals already perpetrated by the abuses of this law will shock the country when they are exposed, as they inevitably will be.”

“Unless amended, it will inevitably succeed in driving every liberal minded and progressive officer from the army. It will leave only the reactionary elements. A future war will then be followed by an aftermath of scandals and investigations worse than the last war.” [Ibid.]

What follows in Malcolm’s letter are similar attacks on his perceived abuses by these “Prussian” style officers, but he fails to detail any specifics. Despite all the charges he leveled at the army, the only solution he offers came in the letter’s last lines.

“Without reform, the regular army had better be abolished. It is a useless expense to the taxpayer in its present form.” [Ibid.]

Others noted Wheeler-Nicholson’s lack of solutions and said so in editorial form.

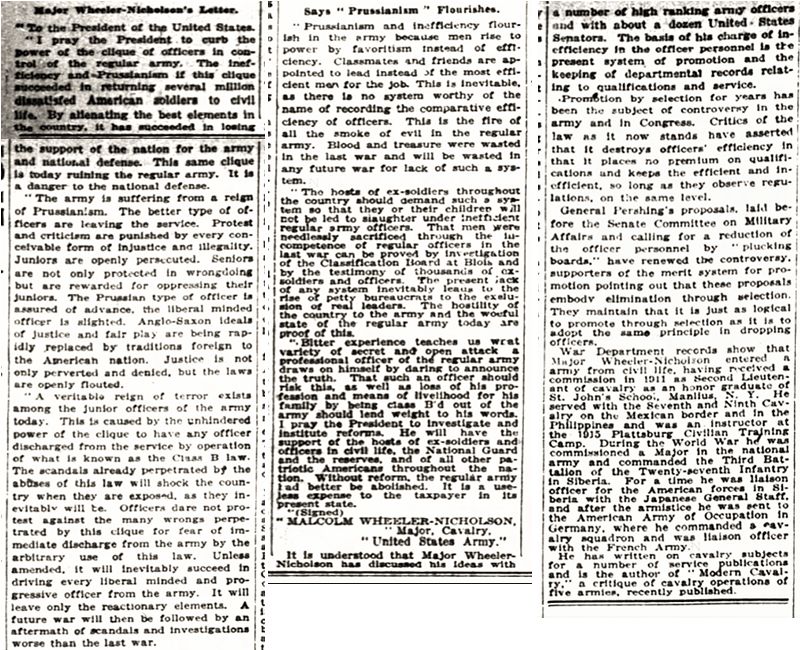

NEW YORK TIMES (Feb. 7, 1922)

“Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, who in a letter to the President makes a sensational attack upon the ranking officers of the regular army responsible for its efficiency, is a man with a grievance. It is that ‘they put me in Class B because I had been in debt as a Second Lieutenant.’ Class B includes officers to whom is given the option of accepting retirement at reduced pay or asking a court to inquire into the charges preferred against them by superiors.”

“There has been a great deal of complaint that officers have not had a square deal when they asked for a court of inquiry. The constitutionality of that section of the Army Reorganization act that provides the machinery for eliminating inefficient officers from the service has been challenged.”

“Major Wheeler-Nicholson may be a victim of prejudice and injustice. But some of the assertions he makes are mere ranting. For instance: ‘Senior are not only protected in wrongdoing but are rewarded for oppressing their juniors.’ Again: ‘A veritable reign of terror exists among the junior officers of the army today.’ The reason given is that no one is safe from the clique which selects names for Class B. ‘The host of ex-officers throughout the country should demand’ says this officer, ‘such a system that they or their children will not be led to slaughter under inefficient regular army officers.’ That all the regular army officers who served in France were competent leaders cannot be maintained, but the average of efficiency was obviously much higher than among the officers who had never had West Point or regular army training.”

“It has been charged that a ‘clique of officers,’ to use a phrase of Major Wheeler-Nicholson’s, controlled the army in France. In a sense it is true, for the fortunes of the American Army were in the hands of West Pointers, happily for the nation and our allies.”

“When Major Wheeler-Nicholson says that the army ‘is a useless expense to the taxpayer in its present state,’ he talks nonsense.” [“Army Plucking Boards,” NEW YORK TIMES, Feb. 7, 1922.]

After this excoriation of Wheeler-Nicholson, the TIMES editorial sums up the writer’s feelings about the Class B law itself.

“The law governing the jurisdiction is not as clearly defined as it might be. But when the worst is said about the operation of Section 24-b of the Act of June 4, 1920, the good intentions and the conscientiousness of most of the officers forming these courts must be admitted.” [Ibid.]

If Malcolm hoped that the tide of public opinion would sway Harding, that hope was beginning to diminish. According to the earlier response Harding had made regarding Malcolm’s reestablishment to the Class A list, the Congress and the War Department were already looking to make changes into the law governing the promotion list. And Malcolm’s call for the abolition of the army based upon his complaints was absurd.

So, exactly what Wheeler-Nicholson hoped to accomplish? One answer may lie in the fact that just the week before he penned his letter to Harding, Wheeler-Nicholson’s book, MODERN CAVALRY, was released on January 24, 1922. Publicity, good or bad, drives book sales.

MODERN CAVALRY title page (1922)

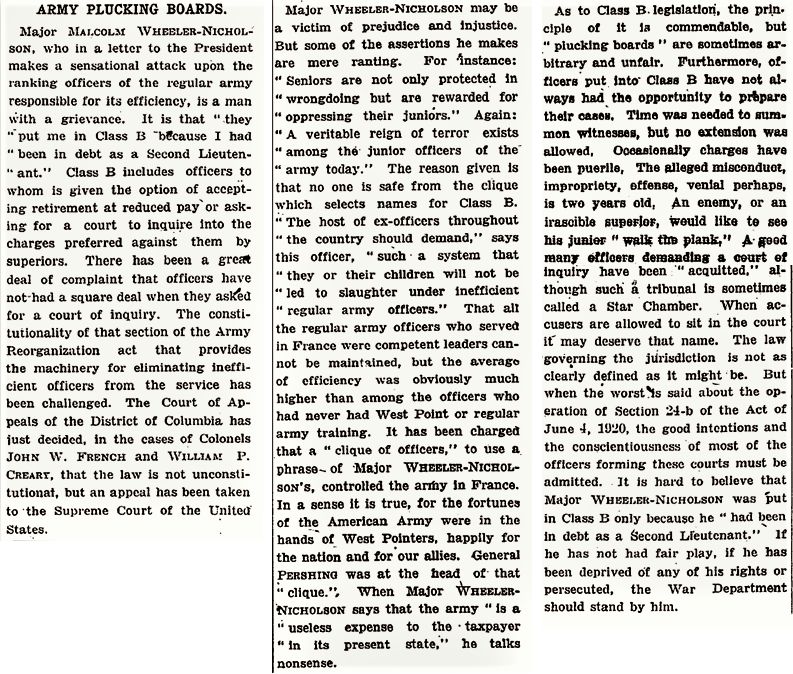

More details regarding Malcolm’s initial Class B ranking came out, along with the news of a court martial he was facing and a strange shooting that he barely survived.

“[Wheeler-Nicholson] being treated at Walter Reed Army General Hospital for an injury to his ear, caused by the mistake of a guard who shot him when he sought to enter for sleep the home of a fellow officer at Camp Dix who was absent, when informed that the intimation had been made that his letter to the President might be an attempt to hide his own ‘precarious status,’ he having been slated for Class B and dismissal for alleged inefficiency, and having been ordered before a court-martial at Camp Dix for alleged absence without leave and alleged disobedience of orders…”

“I have no desire to raise any smoke screen around my own record and treatment in the army. I court the fullest and fairest investigation of the allegations contained in my letter to the President. This is not a personal matter, but much broader. It runs to the very heart of things in the army.” [“Insists He Acted for Good of Army,” NEW YORK TIMES, Feb. 6, 1922.]

NEW YORK TIMES (Feb. 6, 1922)

Wheeler-Nicholson’s shooting is more fully explained later in the article.

“One of the officers who knows him well stated that Major Wheeler-Nicholson entered the home of a friend during the latter’s absence, was mistaken by the caretaker for a burglar and was shot. He was seriously hurt.”

“He arrived at Camp Dix from Washington in the middle of the night last August [1921]. His quarters had been given up and he went to the Officer’s Club to sleep. It was locked and after vainly attempting to get in,he went to the home of an officer whom he knew very well. This officer [Major Francis T. Colby] was away, although Major Wheeler-Nicholson did not know of his absence.”

“He rang the bell and pounded on the door, but received no response. Then he went around to a rear window.”

“’He was foolish, perhaps,’” said the officer who told the story, ‘but of course there was absolutely nothing wrong in what he did. He crawled through the window, seeking a place to sleep.”

“A soldier who was on guard in the house, awakened by the noise, fired, and the bullet struck the Major in the head, inflicting a serious scalp wound.”

“Officers at Camp Dix said that Major Wheeler-Nicholson had been likely to ‘fly off at at tangent,’ and was inclined to find army discipline irksome. This made it hard for him to get along under some of his commanding officers.” [Ibid.]

Reportedly, the bullet entered near his temple, leaving a scar he would bear the rest of his life.

NEW YORK TIMES (Feb. 6, 1922)

More details concerning Malcolm came out in the press. Both the White House and the War Department under Secretary of War, John Weeks, claimed that they hadn’t yet received his letter that ran in the newspaper. And his return to Camp Dix had been made in preparation for his trial “before a military court on charges of being absent without leave and making false official statements.”

“The major denied these charges today, saying they were but a part of ‘a plot to get him.’” [“Wheeler-Nicholson Letter Goes Astray,” BOSTON GLOBE, Feb. 7, 1922.]

Matters would get even worse in coming days. On Feb. 25, the War Department’s Adjutant General, sent a letter to Wheeler-Nicholson asking him to explain in writing if he indeed was the author of the letter, whether he addressed it to the President and if he had directly sent a copy of it to the NEW YORK TIMES. He was advised that he had the right to refuse to answer this request if he felt it would incriminate him.

Malcolm replied in writing.

He admitted to both writing to the President and to giving the letter to the TIMES. He stated he did so to, “secure action toward the removal of evils in the regular army that imperial [sic] the national defense.”

He went on to list “facts” that “proved” the “deep-seated evil in the regular army.” The eight “evils” included a charge that the army “was unready at the outbreak of war,” “that it did not even have a plan of operations ready,” “National disaster would have resulted had the German Army been unwearied,” and “vast number of regular officers earned the ill-will of the citizen soldiers by attempting to cover ignorance with arrogance.” [“Weeks Reprimands Wheeler-Nicholson,” NEW YORK TIMES, Feb. 26, 1922.]

Despite the growing list of charges against him, Malcolm did have his supporters. The Libertarian weekly, THE FREEMAN, came out wholeheartedly behind him, although their support was specific to one of his cost-saving suggestions: “’Without reform,’ says Major Wheeler-Nicholson in closing his letter, ‘the regular army had better be abolished. It is a useless expense to the taxpayer in its present state.’ We quite agree, and we are not in favour of reform.” [THE FREEMAN, Feb. 15, 1922.]

His most consistent and unwavering supporter, as always, was Antoinette. She, too, penned a letter to President Harding and she also made sure that its content made it into the newspaper.

NEW YORK HERALD (March 6, 1922)

“I hereby protest against the return of my son, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, now at Walter Reed Hospital, to Camp Dix, N.J., where he was recently shot through the head and thereafter left without proper care or attention until he nearly bled to death while in an unconscious state, this shooting having followed shortly upon the failure to frame Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson for a court-martial upon false, trivial and trumped-up charges.”

“I beg to inform the President that this order for the return of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, a cavalry officer, to Camp Dix is a part of the conspiracy of persecution designed to drive him from the army, break his health and force him to resign or to silence him by even more drastic methods as a witness against the illegal use and abuse of power confided to officers of the army.”

“Further, that arbitrary breaking of an army regulation to send Major Wheeler-Nicholson to a post where he was isolated from his friends, separated from his family and under the espionage of friends of senior officers who fear to free him in open court, is well know to many officers in the War Department and connived at by them since early in 1921, when Major Wheeler-Nicholson was first sent to Camp Dix, N.J., and refused leave to consult with attorneys or to visit his wife in her illness.”

“I beg, therefore, that the President will not be misled by assurances of officers in the War Department that all is well in the best of all possible War Departments, but that he will insist upon a thorough investigation of conditions that permit the hounding of young and useful army officers out of the service or to their deaths.” [“Major’s Mother Protests,” NEW YORK TIMES, March 6, 1922.]

Antoinette minced no words in making direct accusations of conspiracy and the implication that the army was trying “to silence him by even more drastic methods,” alluding, it’s supposed, to the shooting that took place when he broke into home upon returning to the base late at night. Although it is hard to believe that the army felt so threatened by a letter written by a disgruntled officer that they plotted to kill him, when he could easily be rid of through court martial and dismissal, this suggestion of it being an assassination attempt would be brought up again by Wheeler-Nicholson.

The same day his mother’s letter was published, Malcolm was released from Walter Reed Army Hospital. Immediately, he made three attempts to get an in-person meeting with President Harding. Each request was denied. He took the opportunity, though, to push his view that he was being punished unfairly.

“’I am being ordered to Camp Dix,’ said Major Wheeler-Nicholson, ‘for the infliction of more hardships. It is ideal for the purpose for the War Department, being difficult of access to newspapers and the public. If I am going to be tried by court martial I am going to demand a trial where the public can hear the evidence. It will be a very startling trial and will shed light on the army’s somewhat mediaeval [sic] ideas of justice as well as the workings of the military mind.’”

“I have been bitterly attacked and rather roughly handled. I expect more bitter attacks and rough handling before I make the idea stick. My wife and I have fought, have been ordered hither and yon; we have sold everything to be able to continue fighting. She has pawned most of her jewels, and we intend to continue fighting.’” [“Wheeler-Nicholson Fails to See Harding,” NEW YORK TIMES, March 7, 1922.]

Wheeler-Nicholson had his letters and subsequent remarks printed in his self-published pamphlet, THE REGULAR ARMY—REFORM IT OR ABOLISH IT, which he sent to every member of Congress. His words resonated with at least one. Newly elected Republican Congressman Walter F. Lineberger of California, gave a speech before the house on March 10, citing this pamphlet and calling for inquiries into Malcolm’s charges. Antoinette also made her plea to one powerful politician.

“Mrs. Antoinette Wheeler-Nicholson, the Major’s mother, made public last night a letter she had sent to Senator [William] Borah demanding that if charges were made against her son, that the trial be held in Washington, ‘where the pitiless light of publicity can act as the only possible restraint upon the men in the conspiracy of persecution.’” [“Major Nicholson Issues a Pamphlet,” NEW YORK TIMES, March 8, 1922.]

NEW YORK TIMES (March 8, 1922)

Days later, Malcolm received more bad news.

“Instead of being apprised of the nature of charges which he was informed last Monday the War Department would make against him, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson on his return here [Camp Dix] this morning received a letter advising him that a board of officers in Washington had placed him provisionally in Class B.” [“Army’s Assailant is Put in Class B,” NEW YORK TIMES, March 12, 1922.]

Malcolm’s was understandably upset and he went on a diatribe once again attacking the army, its “system that leads to so much stupid injustice,” and to assert he was doing it “because it is necessary for someone in the regular army to point out the danger to the national defense in continuing a system that antagonizes the native American. The War Department is swathed in coils of red tape until it is like a Chinese woman’s foot.” [Ibid.]

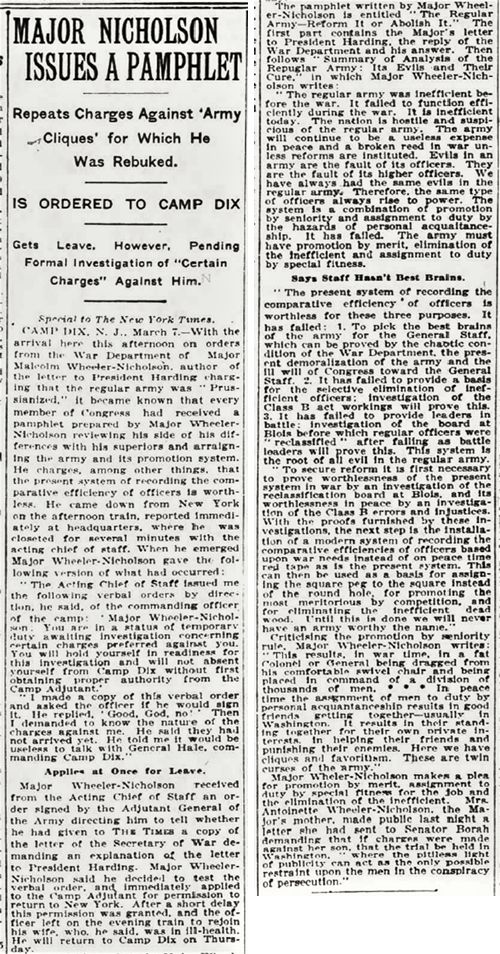

Not only were Malcolm and Antoinette taking to the papers to make his case, his wife Elsa also made hers. An article concerning her led with a sympathetic paragraph sure to pull at the readers’ tstr.

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS (March 13, 1922)

“Sick and broken up over the imminent discharge from the army of her husband, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, Mrs. Elsa Carolyn Wheeler-Nicholson is confined at the Grand Hotel, refusing all callers.”

“Four alleged attempts to frame him for court-martials have failed,the major’s mother said yesterday. She declared she was almost impoverished after spending $15,000 to defend her son.” [“Wife of Army’s Stormy Petrel Ill Over Attack,” NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, March 13, 1922.]

Antoinette’s claim that she had spent “$15,000” of her own money to defend Malcolm is odd, considering that he had claimed he bailed his parents out when they didn’t have the money to spend on his brother’s education.

Wheeler-Nicholson decided to once again make an appeal directly to President Harding. This second letter was even more direct than the first as he implored the President to “restrain” the War Department from “further lawbreaking.”

“I have in addition,” wrote Malcolm, “proofs that the same conditions that led to the Dreyfus case in the French army are in existence today in the American army. I have proofs of a startling record of persecution and conspiracy, of deliberate attempts to drive an officer from the army by breaking him financially, by scattering his family, by continually bringing false and baseless charges, and by the infliction of almost unbelievable injustice and illegality.”

“I will prove,” he continued, “that the same system that can perpetrate such wrongdoing in peace time, was responsible for the wasted lives of good American soldiers in battle. I will prove exactly where and when they were wasted and who wasted them.” [Major Again Appeals to Harding on Army,” NEW YORK TIMES, March 26, 1922.]

Either Wheeler-Nicholson was in the possession of bombshell information that would bring down the top ranking Army establishment, or he was desperately bluffing. He would soon get his opportunity to present his “proofs,” if he had them, when he went on trial at his court martial.

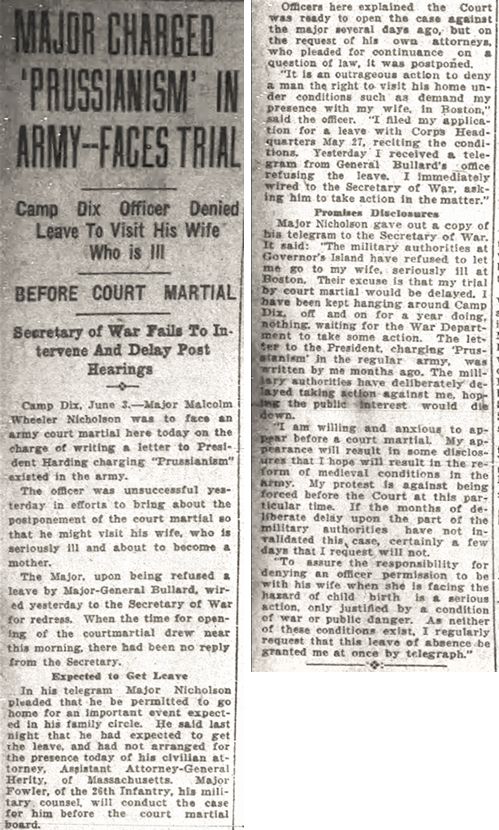

CAMDEN COURIER-POST (June 3, 1922)

“Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson was to face an army court martial here today on the charge of writing a letter to President Harding charging ‘Prussianism’ existed in the army.”

“The officer was unsuccessful yesterday in efforts to bring about the postponement of the court martial so that he might visit his wife,who is seriously ill and about to become a mother.”

“The Major, upon being refused a leave by Major-General Bullard, wired yesterday to the Secretary of War for redress. When the time for the opening of the courtmartial [sic] drew near this morning, there had been no reply from the Secretary.”

“In his telegram Major Nicholson pleaded that he be permitted to go home for an important event expected in his family circle. He said last night that he had expected to get the leave, and had not arranged for the presence today of his civilian attorney, Assistant Attorney-General Herity of Massachusetts. Major [Godfrey R.] Fowler, of the 26th Infantry, his military counsel, will conduct the case for him before the court martial board.” [“Major Charged ‘Prussianism’ in Army—Faces Trial,” CAMDEN COURIER-POST, June 3, 1922.]

Wheeler-Nicholson had presented affidavits from Boston doctors affirming his wife’s illness and he requested a 20-day leave of absence. The court refused, likely suspicious of the timing of Elsa’s illness, and his last ditch telegram to Secretary of War Weeks got no response.

As far as his representation was concerned, Malcolm needn’t worry about his military counsel. While he may not have had the political heft of an Assistant Attorney General, Major Godfrey Rees Fowler was well-regarded within the ranks of army attorneys. And perhaps more importantly, he was a battlefield-tested veteran of the Spanish-American War. Still, Malcolm felt the need to interject: “I have every confidence in Maj. Fowler. I also fear for him. It should seem that any officer who comes to my defense is place in a rather serious position. This was proved at my last trial when my military counsel was dropped from the Army after defending me.” [“Maj. Nicholson Put on Trial,” BOSTON GLOBE, June 4, 1922.]

Major Fowler was able to get one of the charges against Malcolm withdrawn on the first day. The claim was that Wheeler-Nicholson had gone AWOL from June 9, 1921, to July 23, 1921. An officer was produced by the defense who said he had spoken to Malcolm on July 11, 1921, thereby verifying his claim that he had been on leave with permission.

A second serious charge was also quashed after some debate. It was alleged that Malcolm had made a false official statement regarding a meeting he had obtained with Army Chief of Staff, Gen. John J. Pershing. Wheeler-Nicholson claimed that this meeting resulted in his delay of applying for a leave of absence to his commanding general at Camp Dix, due to his detainment “by necessary compliance with the personal orders of General Pershing for special report on some military matters.” [“Major Reiterates Prussianism Charge at Court-Martial,” PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER, June 4, 1922.]

Pershing disputed Malcolm’s characterization of their meeting and filed an affidavit to the court explaining his point of view.

“The affidavit of General Pershing told how the Major, with former Senator Chamberlain, visited the General’s office in July [1921]. at which time the Major started a lengthy verbal discussion regarding his reduction to ‘Class B.’ General Pershing said he had ended the interview by instructing Major Wheeler-Nicholson to reduce what he had to say to writing. The General said this was given merely as a suggestion, and, in his opinion, could not be construed as an order.” [Ibid.]

After meeting with the attorneys for both sides, the court ruled that Pershing’s affidavit must be construed as an opinion and not a statement of fact and therefore could not be used against Wheeler-Nicholson.

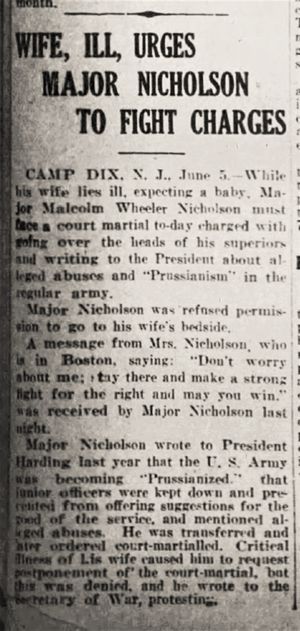

Much was made in the press of Elsa’s illness, with many reports claiming that she was pregnant. That assertion was doubtful unless she miscarried soon after. Her next child, Marianne, was born on July 4, 1923, 13 months after the court martial. Malcolm used the court’s “…refusal to grant me leave to be with my wife only proves what I have contended: Namely, that any junior officer who dares to announce the truth about army conditions draws on himself secret and open attack.” [“Maj. Nicholson on Trial for Criticizing Army,” BOSTON GLOBE, June 5, 1922.]

Despite her dire illness, Elsa was able to wire Malcolm her support and he in turn, inspired by her message, “was willing to be a ‘martyr’ to improve conditions for junior officers.” [“Wife Cheers Nicholson,” NEW YORK TIMES, June 5, 1922.]

With two of the three charges against Wheeler-Nicholson dismissed, the prosecution’s only remaining win would depend upon the argument made by Lieut. Col. Allen J. Greer. As impressive as the defense counsel’s credentials were, Greer’s were even more so. He not only had fought in the Spanish-American War, but also in the Philippine Insurrection and in the Great War. He also possessed the Medal of Honor for capturing an enemy outpost in the Philippines alone and armed only with a pistol.

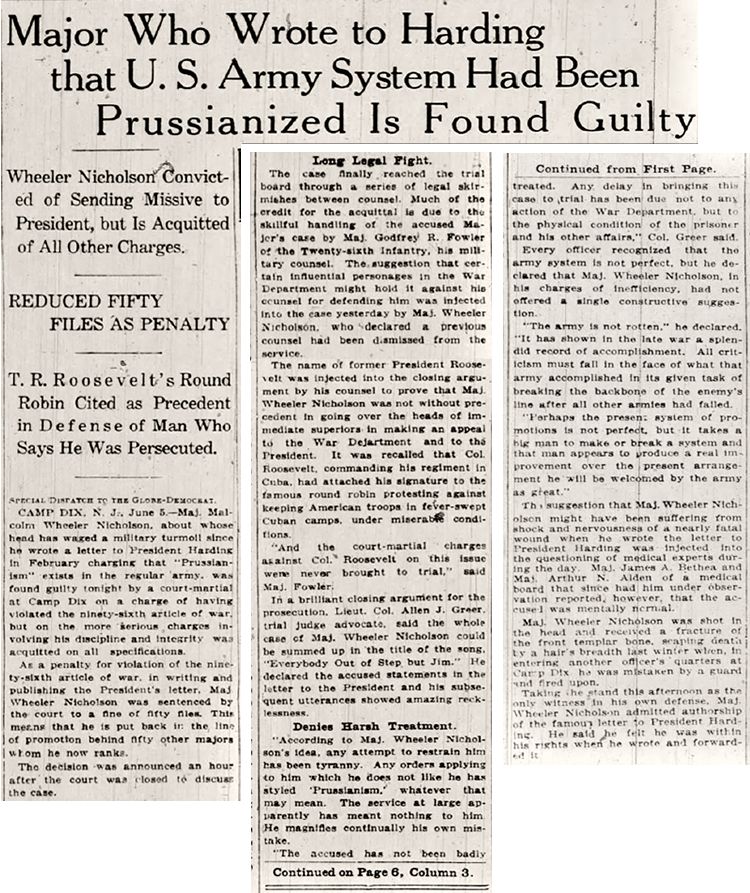

“In a brilliant closing argument for the prosecution, Lieut. Col. Allen J. Greer, trial judge advocate, said the whole case of Maj. Wheeler Nicholson could be summed up in the title of the song, ‘Everybody Out of Step buy Jim.’” He declared the accused statements in the letter to the President and his subsequent utterances showed amazing recklessness.” [“Major Who Wrote to Harding that U.S. Army System Had Been Prussianized is Found Guilty,” ST. LOUIS GLOBE-DEMOCRAT, June 6, 1922.]

ST. LOUIS GLOBE DEMOCRAT pgs. 1 & 6 (June 6, 1922)

Although he had the title slightly wrong—it was actually “They Were All Out of Step But Jim”–Greer’s invocation of the song instantly encapsulated the Army’s perception of Malcolm and would resonate with the public as well.

“’According to Maj. Wheeler Nicholson’s idea, any attempt to restrain him has been tyranny. Any orders applying to him which he does not like he has styled ‘Prussianism,’ whatever that may mean. The service at large apparently has meant nothing to him. He magnifies continually his own mistake.’”

“’The accused has not been badly treated. Any delay in bringing this case to trial has been due not to any action of the War Department, but to the physical condition of the prisoner and his other affairs.’”

“Every officer recognized that the army system is not perfect, but he declared that Maj. Wheeler-Nicholson, in his charges of inefficiency, had not offered a single constructive suggestion.”

“’The army is not rotten,’ he declared, ‘It has shown in the late war a splendid record of accomplishment. All criticism must fall in the face of what that army accomplished in its given task of breaking the backbone of the enemy’s line after all other armies had failed.’”

“’Perhaps the present system of promotions is not perfect, but it takes a big man to make or break a system and the man appears to produce a real improvement over the present arrangement he will be welcomed by the army as great.’” [Ibid.]

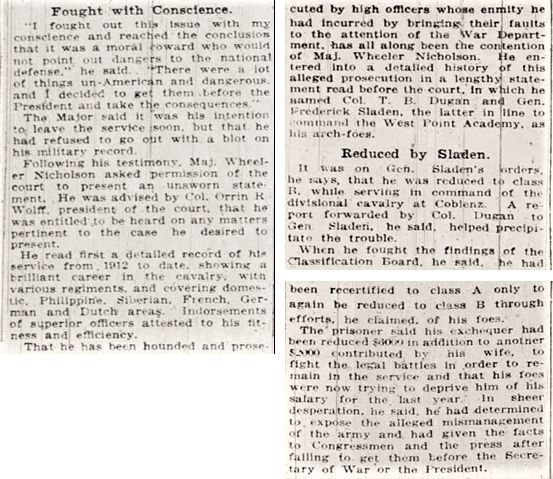

ST. LOUIS GLOBE-DEMOCRAT pg. 6 (June 6, 1922)

In the end, it was Wheeler-Nicholson’s own admission of having written the letter to President Harding that convicted him under the 96th Article of War for going over the head of his superior officers. Consequently, the results of the court martial were mixed, with both sides having won some part of their case. The newspapers across the country reported the outcome differently as well, with some stressing Malcolm’s acquittal on the two charges, while others focused on his one guilty conviction.

The court recessed and came back within an hour with his punishment. Malcolm was to be fined 50 files, meaning that he was to drop 50 places on the promotion list behind other majors that he currently out ranked. It was a relatively minor rebuke and not at all the grievous reprisal Malcolm had been predicting to the press.

Yet, Wheeler-Nicholson knew his military career was over. Even if he stayed in the service, his career was effectively at a dead-end. He had about two months to consider his options when the army let him know that they weren’t finished with him yet.

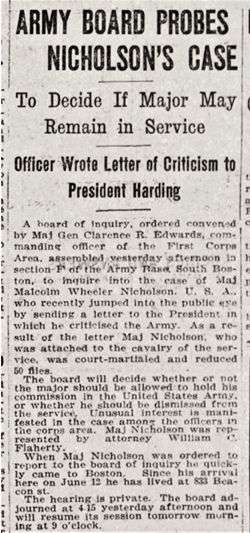

“A board of inquiry, ordered convened by Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Edwards, commanding officer of the First Corps Area, assembled yesterday afternoon…to inquire into the case of Maj. Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson U.S.A., who recently jumped int the public eye by sending a letter to the President in which he criticized the Army.”

“The board will decide whether or not the major should be allowed to hold his commission in the United States Army, or whether he should be dismissed from the service.” [“Army Board Probes Nicholson’s Case,” BOSTON GLOBE, Aug. 4, 1922.]

BOSTON GLOBE (Aug. 4, 1922)

This was bad news. If the board decided to keep Malcolm in Class B, he would be dismissed, which was the equivalent to a dishonorable discharge for an enlisted man. It would be the ultimate disgrace. To avoid that possibility, he immediately requested retirement from the army due to physical disability.

“In reply to the request for retirement, the Secretary of War has said that no action will be taken until the arrival of the records of the board of inquiry.”

“Through his attorney, Maj. Nicholson made the following statement to a Globe reporter: ‘I am not on trial; the War Department is on trial. My trial took place at Camp Dix when the War Department piled against me charges for everything under the sun, and every charge was turned down except the charge of having written a letter to the President.’” [“Attempts to Prove Officer Persecuted,” BOSTON GLOBE, Aug. 5, 1922.]

When the board of inquiry was finally convened in the First Corps Area in South Boston, his civilian attorney, William Flaherty, charged that Malcolm’s entire military record wasn’t available at the hearing. He claimed that only “those derogatory to the officer, but none of the letters or communications which commended him or exonerated him from any of the charges were there.” [“Records Incomplete, He Objects,” BOSTON GLOBE, Aug. 21, 1922.]

“Several of the records gone through this morning referred to the major’s work in France in charge of supplies that were missing. The officer’s defense was that the supplies were either stolen by some civilian or while on the boar. In each case, he said, the officer was exonerated, but none of the data relative to the exoneration was at the hearing.”

“The officer [Wheeler-Nicholson] in one charge was said to have overdrawn his pay. The officer admitted the error, and had already made preparation with the War Department to pay the money back at $50 each month. The major said that he was exonerated on this charge, but the records were missing.” [Ibid.]

More charges were leveled and Flaherty deflected each. When once again Malcolm was cited for an instance of being absent without leave (AWOL), he had an answer for that as well.

“It was brought out that the major was refused leave several times and then leave was granted and while he was on leave, the leave was revoked.”

“The attorney [Flaherty] said that there was another effort to destroy the officer [Wheeler-Nicholson]. He charged that it was a conspiracy by a few officers. ‘Common humanity demands that a man rush to the aid of his wife. The major was doing this when he asked for his leave.’” [Ibid.]

“Another charge was that the officer [Wheeler-Nicholson] wore insignia of a major while still a captain, and signing papers as captain. The major is ready to prove that he was a major six months before the charge was made.” [Ibid.]

At the last session of the inquiry board on August 23, Flaherty made his final arguments. He stated that the present system relied too heavily upon negative evaluations at the expense of positive ones; that Wheeler-Nicholson had been the victim of a vindictive cabal of superior officers, particularly Brig. Gen. Sladen and Gen. Bailey, who Flaherty accused of conspiring to frame his client. The defense cited the basic unfairness of military law, that in his mind, placed the word of a superior officer above that of a junior. Several of the charges against Malcolm, according to Flaherty, that they weren’t even worth mentioning. He closed with an anecdote about President Theodore Roosevelt’s consideration of a complaint from a Navy admiral. “If Admiral Sims is wrong, I’ll court-martial him, but if he is right, I’ll promote him.”

“Mr. Flaherty said: ‘That is the system that should prevail in the army. That is the system that will encourage junior officers to made [sic] constructive criticism and no superior officer ought to have the right to crush out this ambition. If you destroy the constructive criticism, you destroy the institution.” [“Says Army System Cannot Last in America,” BOSTON GLOBE, Aug. 23, 1922.]

Ultimately, the board of inquiry ruled that Wheeler-Nicholson’s appeal to be removed from Class B was refused. Once again, Malcolm, on November 16, appealed directly to President Harding to overrule this ruling. In this letter, Malcolm expanded the circle of prejudice against him to include the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Pershing.

In a curious move, Malcolm was ordered to enter Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C., for treatment in December 1922. He had previously requested retirement based upon physical disability and this may have been a way of evaluating his claim.

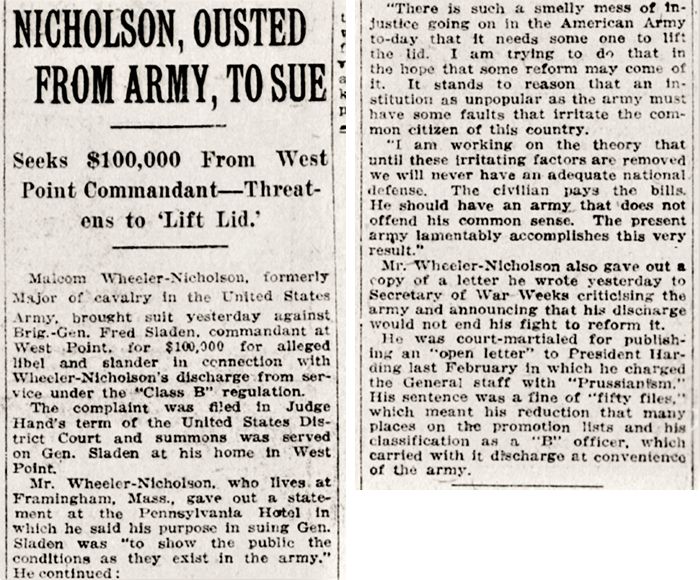

On December 16, Wheeler-Nicholson sent a communication to the War Department that he was considering a lawsuit against Major Gen. Sladen, now the Superintendent of West Point, for $100,000 in damages for lies he claimed were told by the general.

Major Gen. Fred W. Sladen (1925)

Cleared by the doctors at Walter Reed as healthy and receiving no clemency from President Harding, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson was involuntary honorably discharged from the U.S. Army. His discharge was described in various ways by various newspapers, some stating that he had been “cashiered,” others that he had been “dismissed.” But the simple designation of “honorably discharged” was likely an agreed-to settlement to allow Malcolm to leave the service with some dignity and to avoid any further court actions by him. He may not have been happy, but he had no choice.

But Malcolm wasn’t done. On December 30, 1922, he filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court of Judge Learned Hand, “for $100,000 for alleged libel and slander in connection with Wheeler-Nicholson’s discharge from service under the ‘Class B’ regulation.” [“Nicholson, Ousted from Army, to Sue,” NEW YORK HERALD, Dec. 31, 1922.]

NEW YORK HERALD (Dec. 31, 1922)

This case and a similar suit brought by Malcolm in Federal Court, made it’s way through the court system for a year. On January 4, 1924, newspapers reported that the state case had been dismissed by the New York Supreme Court. About a week later, on January 15, 1924, the Federal case was dismissed as well.

Were these the actions of an unjustly persecuted man, determined to fight his accusers to the end? Was he an idealist looking to change an unfair system? Or was he a spoiled man of privilege, unable to accept a negative evaluation from superiors, unable to believe that the same rules applied to him as they did to any other soldier, who reacted with a public tantrum? And how much of an influence did his ubiquitous mother have on his decisions?

Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson certainly looked the part of a cavalry officer, but his greatest accomplishments came on the polo field. The West Pointers he railed against, particularly those who had made their reputations in the Spanish-American War or the Philippines or on Flanders Fields, most likely fumed at the thought that such a man would dare paint himself as an expert in military tactics.

It seems fair to say that Wheeler-Nicholson had a penchant for self-aggrandizement, exaggeration and the occasional lie if it suited his purpose. In this, his mother Antoinette certainly set the example. She was also quick to utilize her connections in the media and in politics if it was to Malcolm’s benefit. Apparently Malcolm’s tendencies were obvious to his military superiors as well, as they were all noted by Gen. Sladen in the evaluation of Wheeler-Nicholoson that led to his original demotion to the Class B list.

Despite his protestations, Wheeler-Nicholson had chosen an unwinnable battle. At best, it was a quixotic quest. He knew from the beginning that by being a service member, the Uniform Code of Military Justice superseded civilian laws. When his defense attorney, Major Fowler, cited Malcolm’s right to petition the President under the First Amendment, it fell on deaf ears, as all knew it didn’t apply to a soldier in uniform.

Yet, a life isn’t just one action, one event, or one select time period.

A life is determined by many factors: By genetics, by upbringing, by environment and by life experiences, all of which form the person we become and inform the subsequent life we will lead. This has been one life revealed up to a point. A defining point, but more were to come. This portion of Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s story stops here, but it certainly didn’t end.

He had other battles to fight.

2 Comments; ?>

An incredible amount of data to unpack. An impressive amount of research conducted all over digging into ancient archives. There are not a lot of us left who seek uncovering all the stones in the time lines peering past the mythic illusion legends created by corporations. Those of us who do, however, love building upon the back & side bar stories. Bravo!

Thank you, Bob! Coming from a legendary comics historian such as you, who has done some awesome researching of your own, your kind words are truly appreciated!