Max C. Gaines and George J. Hecht

©2019 Ken Quattro

It was 1941 and the debate about the effects of comic books on the youth of America had been raging in earnest for over a year. Sterling North’s article, “A National Disgrace,” published on May 8, 1940 had jump-started the discussion and the comic book industry had been on the defensive ever since.

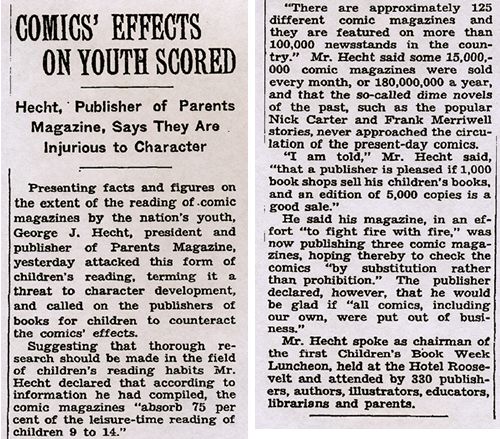

Within the comic book community differences in how to approach the criticisms being leveled varied greatly. The publishers of Superman, DC, put together an Editorial Advisory Board and established an editorial code of ethics. Meanwhile, George Hecht, president of Parents’ Magazine Press, publishers of TRUE COMICS and REAL HEROES, took an entirely different tack. He hoped for the abolition of ALL comic books. Including his own.

NEW YORK TIMES (Nov. 6, 1941)

Hecht’s comments didn’t sit well with M.C. Gaines of All-American Comics. Unlike Hecht, whose main source of income came from publication of PARENTS magazine, comic books were his bread and butter. While Gaines had his own concerns about the effects comics may have upon children’s reading, he took issue with Hecht’s all-inclusive condemnation of the industry.

While both men were publishers, they are arrived at their positions in vastly different ways. A wealthy, New York City born Jew, Hecht attended Cornell University, graduating in 1917. Before following his father into the wholesale hides and skins business, he worked for the Federal government at the Bureau of Research of the War Trade Board. While there, he “conceived the idea of sending bulletins to cartoonists throughout the country giving them suggestions for patriotic cartoons.” [“A Bureau of Cartoons,” CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS, vol. XX #38 & 39, pg. 452 (July 1918.)]

After initially rejecting Hecht’s brainstorm, the Committee on Public Information, essentially the propaganda department formed during the Great War (aka World War I), signed onto the concept and formed the Bureau of Cartoons beginning May 31, 1918. This bureau lasted until the end of the war in November 1918, and spawned a book the next year, THE WAR IN CARTOONS, compiled and edited by Hecht.

Educated in the Ethical Culture movement, Hecht was able to combine his interest in social service with his early success in publication by assuming the position of editor of BETTER TIMES, a vest pocket-sized paper devoted to improving housing for the poor. Child welfare soon became his main focus and in 1926, he founded PARENTS MAGAZINE and the publishing company, Parents’ Institute.

Gaines was also New York City-born and Jewish, and originally bore the less-Anglo sounding name of Max Ginsburg. His father Abraham owned a remnant shop, a “rag dealer” was the common term, and while still a toddler, Max suffered a leg injury in a fall from a fire escape that resulted in life-long pain. Nonetheless, Max served in the Great War, attaining the rank of Second Lieutenant. Somewhere around this time he changed his name to Max Gaines. His work history was vague and eclectic: he reportedly was part-owner of an amusement company, worked as a haberdasher and, supposedly, was even a school teacher.

Gaines didn’t really find his niche until he got a job as a salesman at Eastern Color Printing. It was while working there, said Gaines, that he came up with the concept of producing a tabloid reprinting various comic strips and selling them to their clients as promotional premiums. Although there were similar attempts previously and while some say Harry Wildenberg, Gaines’ boss, was more deserving of the credit, Gaines claimed it to be the birth of the modern American comic book.

Gaines parlayed this coup into a job with the McClure Syndicate, where he packaged comic books for Dell Publishing. His biggest break came when his assistant, a very young Sheldon Mayer, supposedly discovered a comic strip in the company’s “slush pile” of material. He thought it had potential, so he brought it to Gaines. Details of the story vary, but the strip was “Superman” and an icon was born.

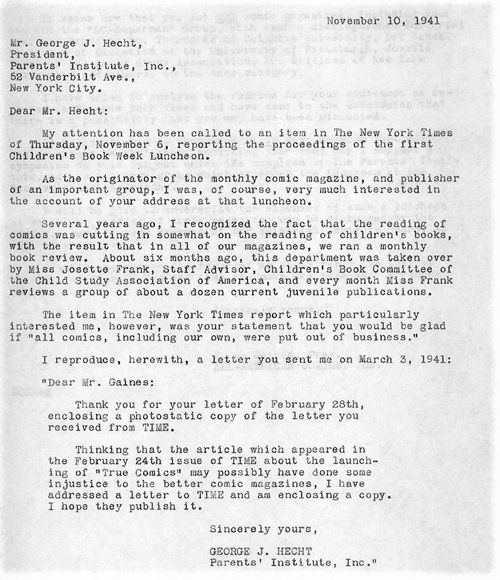

Gaines’ reward for bringing “Superman” to Harry Donenfeld, the new owner of Dectective Comics, Inc., was a partnership with Donenfeld’s right-hand man, Jack Liebowitz, in yet another venture, All-American Comics. He was several years into that role when Hecht’s NEW YORK TIMES article appeared on Nov. 6, 1941. Gaines wrote Hecht with his response and a proposal.

Max C. Gaines letter to George J. Hecht, pg. 1 (Nov. 6, 1941)

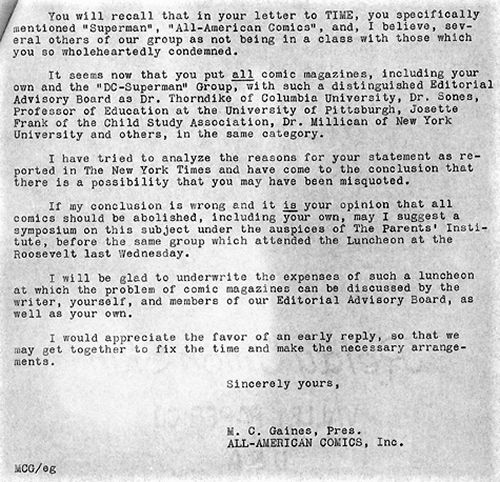

Max C. Gaines letter to George J. Hecht, pg. 2 (Nov. 6, 1941)

Gaines’ reference to the TIME magazine article, was likely evoked by the line which lumped all comic books together as “an overseasoned, indigestible, nerve-shattering, eye-ruining diet of non-comic murder, torture, kidnappings, sex-baiting.” [“Racketeers of Childhood,” TIME, pg. 48. (Feb.. 21, 1941.)]

What had changed since Hecht first wrote Gaines back in June? Hecht had cast himself to Gaines as the industry’s defender, yet now he was seemingly willing to throw them all under the bus, himself included.

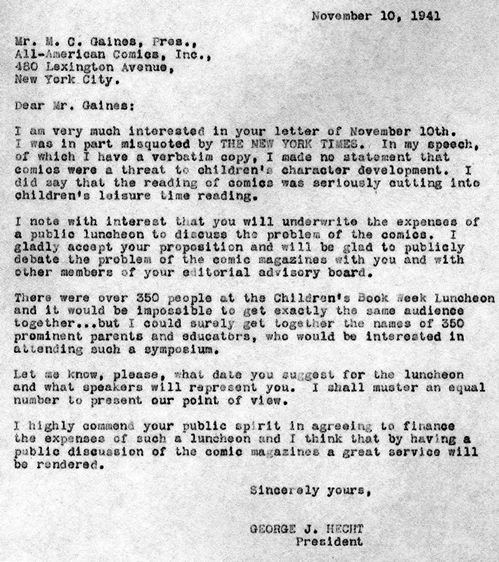

Hecht responded to Gaines letter immediately. He accepted the latter’s proposal of a symposium under the auspices of the Parents’ Institute with funding by Gaines.

George J. Hecht letter to Max C. Gaines (Nov. 10, 1941)

What came of this exchange of letters? Apparently, according to a November 22nd letter written by Gaines to Josette Frank of the Child Study Association of America (CSAA), he responded to Hecht’s letter, but in turn, heard nothing more from Hecht about the proposed symposium.

Perhaps the reason was simply that there were more important events to deal with. On December 7, 1941, just a few weeks after these communications, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and drew the United States into war. The fate of comic books would have to wait.

Some years hence, there would be symposiums discussing the effects of comic books upon children and Hecht would be a part of at least one of them. Gaines never got the chance. But that’s a story for another day.