Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson (1917)

©2019 Ken Quattro

As with all soldiers, Second Lieut. Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson spent his first months in the Army in training. Upon finishing his instruction at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, he was temporarily assigned to Fort Meade in South Dakota to await the return of the Second Cavalry from the Philippines. He finally joined up with them when they arrived at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas in June 1912.

“With the arrival of the Mexican federal troops in Juarez, the United States troops stationed at Fort Bliss, with the exception of the Second cavalry, will return to their respective stations.”

“The principal reason for the strong patrol along the border has been to prevent gun-running and ammunition smuggling and, of course, this precaution is needless when the principal border towns are again in the hands of the federals.” [“Ft. Bliss News,” Aug. 20, 1912.]

It was a period of relative calm along the border. The Treaty of Ciudad Juárez signed in May 1911 by the warring forces of the Mexican federal government of Porfirio Diaz and the revolutionaries led by Francisco Madero, had temporarily eased tensions. Both sides feared American intervention, particularly in the state of Chihuahua which shared a border with El Paso and within easy reach of the American troops at Fort Bliss..

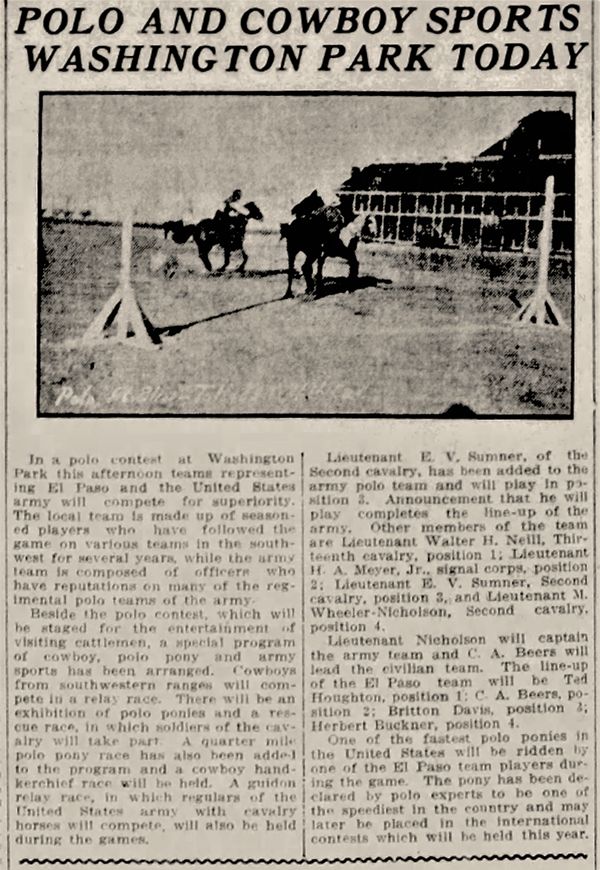

Malcolm was assigned to Troop K, under the command of Capt. Joseph S. Herring and stationed at the Santa Fe Bridge, which spanned the Rio Grande and connected El Paso to Ciudad Juárez. Later, in April 1913, he and his troop were re-stationed at the small border town of Sierra Blanca. Contact with Mexican bandits were infrequent, so the lack of actual conflict allowed Malcolm time to pursue one of his great passions. Playing polo. He not only made the post’s polo team that competed against a team of civilians, he was named as its captain.

EL PASO TIMES (March 20, 1913)

Wheeler-Nicholson’s name came up in the local newspapers often; as a host of dinner parties, attending Army fetes and organizing horse shows and events. It came to an end, though, in December 1913 when he was reassigned along with the rest of his regiment, to Fr. Ethan Allen in Vermont where they were to train elements of the Army National Guard.

The entirety of Troop M, which included Malcolm and under the command of Capt. Edward L. King, spent the summer of 1914 in the city of Burlington as instructors for the Student’s Army Training Course. This precursor to the present day Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC), offered students at the University of Vermont a summer camp program in preparation for America’s possible entry into the war raging in Europe. Then in September, the entire Second Cavalry Regiment participated in field maneuvers in Plattsburg Barracks, New York.

Once again, Malcolm’s skill as a horseman provided him with the opportunity to participate in horse shows and polo games in various venues in the northeastern states. Much of Lieut. Wheeler-Nicholson’s military career was covered in Oregon newspapers, most likely thanks to his mother.

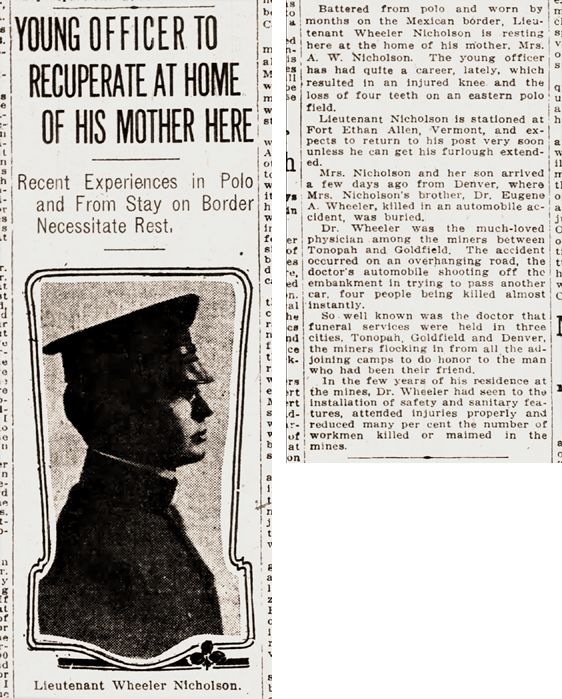

“The young officer has had quite a career, lately, which resulted in an injured knee and the loss of four teeth on an eastern polo field.” [“Young Officer to Recuperate at Home of His Mother Here,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, July 12, 1914.]

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (July 12, 1914)

The next year, the Second Cavalry returned to Plattsburg to assist in Major Gen. Leonard Wood’s innovative plan to train a group of American “blue bloods” to fill the needed officer positions that were going to be needed in the coming conflict.

“By August over a thousand had enrolled, and 1,300 were on hand for the camp’s opening on August 10 [1915].”

“ Officially, these somewhat overweight men, most of them in their late thirties and early forties, were motivated by undiluted patriotism and the spirit of self sacrifice. Actually, they felt they were off on a great adventure. To them the ponderously styled United States Military Instruction Camp—known more familiarly and readily as the Business Men’s Camp—was a chance to learn man’s oldest trade, to say nothing of allowing them to leave the world of banks and offices behind with full public approval.” [“When Gentlemen Prepared for War,” AMERICAN HERITAGE, vol. 15 issue 3, April 1964.]

Soon after, Malcolm received his next assignment. On Nov. 15, 1915, he was transferred to the Ninth Cavalry Regiment and was being sent overseas to the Philippines. There, he would take command of the Ninth’s Machine Gun Troop, which, like all the rest of the Ninth Cavalry, was entirely manned by African-American soldiers.

Malcolm was with the troops of the Ninth Cavalry onboard the U. S. S. Sheridan transport ship coming out of San Francisco, when it made port in Honolulu, Hawaii enroute to the Philippines. On the night of January 14, a number of the soldiers from the ship were entertained at a luau given for them by the resident 25th Infantry, another African-American regiment.

Many of the men from both groups became intoxicated and began wandering the streets of the Iwilei district, Honolulu’s “red light” area. Reports varied, with women in the district claiming they were the object of unwanted advances, homes being vandalized and numerous fights between soldiers. A contingent of White troops from the 2nd Infantry were called in, and with fixed bayonets, they arrested every Black soldier on the street. Both outfits blamed the other for starting the fighting and in the Army investigation that followed, in each case, their officers backed their stories.

“It is understood that officers of the 9th cavalry say their own provost guard was able to restore order in Iwilei and that this guard has cleared the district and gone back to the ship before the 2nd infantry appeared in response to the hurry called by the police when the police found the situation beyond civil authority.”

“Officers of the 9th Cavalry and of the 25th Infantry all refuse to place blame on their own men and those in command of each of the negro regiments seem to believe men of the other regiment were principals in the riot.” [“Reports About Iwilei Rioting are Conflicting,” HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, Jan 18, 1916.]

No matter who was to blame, it can be assumed that Army headquarters wasn’t happy about the public melee and the resulting black eye. There were 12 officers in command of the soldiers of the Ninth involved in that fight, including Malcolm. Such events usually reflected badly on the officers in charge.

When the Ninth Cavalry finally reached the Philippines, it was in a period of peace after years of fighting between the occupying American forces and the indigenous people.

The Moro Rebellion, which involved the mostly Muslim autonomous region in the southern Philippines revolting against the American occupation and rule, had been put down by U.S. forces in 1913. To replace the departing Seventh Cavalry that was redeployed, the Ninth Cavalry “Buffalo Soldiers” were sent in and stationed at Camp Stotsenburg in early 1916.

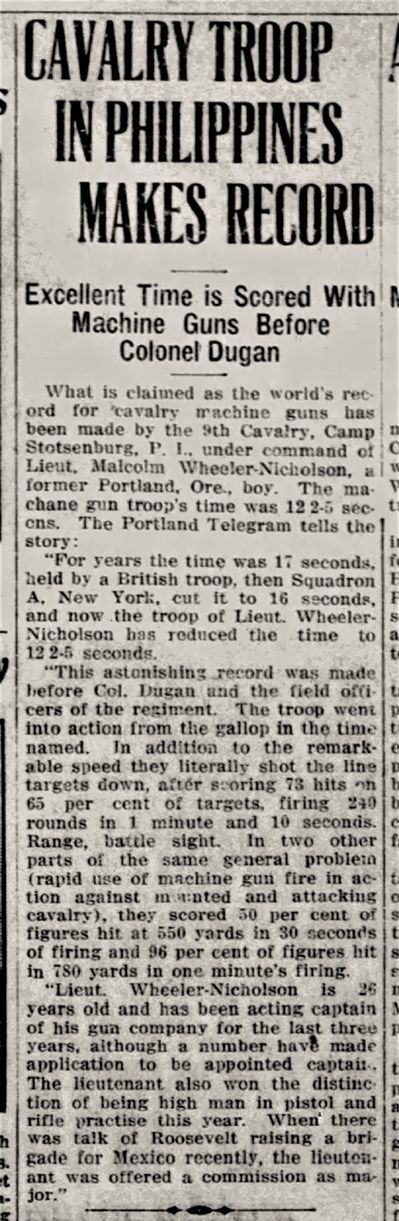

As there was no ongoing conflict in the Philippines, the Ninth’s mission was to stay in combat readiness through rigorous training. Lieut. Wheeler-Nicholson apparently excelled at his assignment, as in August 1916, his Machine Gun Troop set several unofficial world records for speed and accuracy.

It is an interesting comparison of reporting to read how this accomplishment was reported in mainstream White newspapers and in Black ones. Both articles quoted are referencing the record set for the time it took the troop to shoot a machine gun from a full gallop.

“What is claimed as the world’s record for cavalry machine guns has been made by the 9th Cavalry, Cap Stotsenburg, P. I., under command of Lieut. Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, a former Portland, Ore. boy.”

“For years the time was 17 seconds, held by a British troop, then Squadron A, New York, cut it to 16 seconds, and now the troop of Lieut. Wheeler-Nicholson has reduced the time to 12 2/5 seconds.” [“Cavalry Troop in Philippines Makes Record,” HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, Sept. 23, 1916.]

HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN (Sept. 23, 1916)

This article, which originally appeared in the PORTLAND TELEGRAM, goes on to detail the other record-setting scores without once mentioning the race of the men who actually set the record, but it devotes another paragraph to Wheeler-Nicholson and his personal military career. [note: contrary to the claim that he had been “acting captain of his gun company for the last three years,” Malcolm was appointed only months before.] Compare that to the same shooting record as reported in a leading Black newspaper.

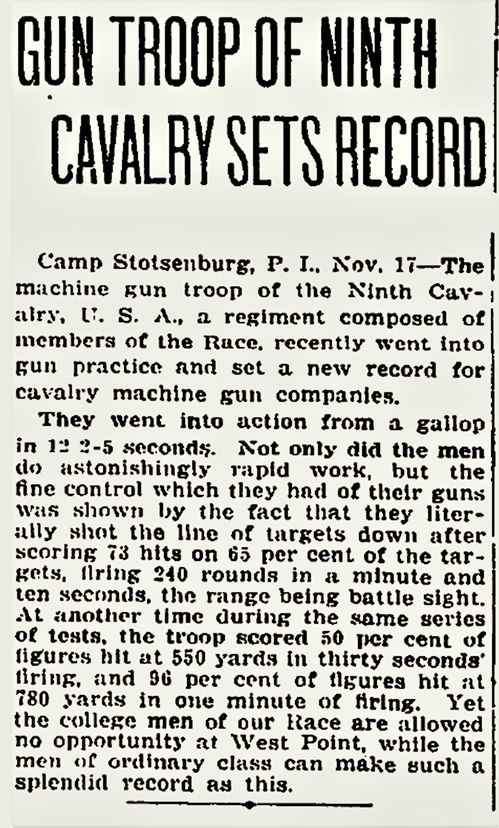

“The machine gun troop of the Ninth Cavalry, U. S. A., a regiment composed of members of the Race, recently went into gun practice and set a new record for cavalry machine gun companies.” [“Gun Troop of Ninth Cavalry Sets Record,” CHICAGO DEFENDER, Nov. 18, 1916.]

CHICAGO DEFENDER (Nov. 18, 1916)

No mention is made of Wheeler-Nicholson, instead the remainder of the article is devoted to details of the records and this closing commentary.

“Yet the college men of our Race are allowed no opportunity at West Point, while the men of ordinary class can make such a splendid record as this.” [Ibid.]

The harsh reality was that Black officers were rarely put in command of Black troops in this era. Through no fault of his own, Malcolm was the beneficiary of the military’s institutional racism.

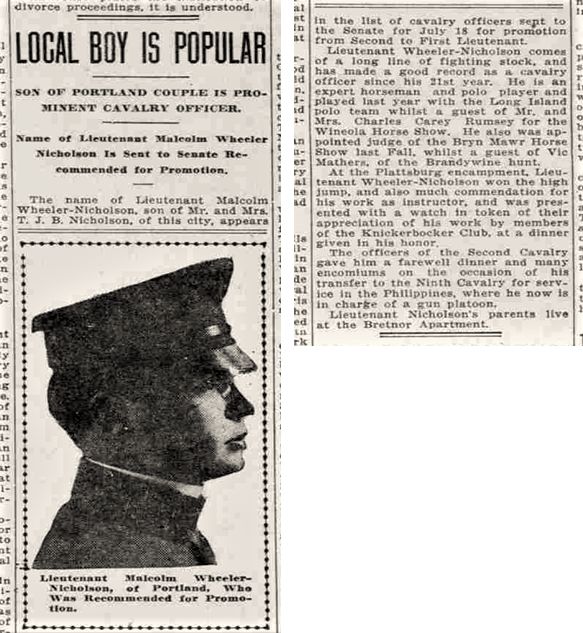

While the shooting record gave Wheeler-Nicholson some national notoriety, most mentions of him and his exploits came, unsurprisingly, in Oregon newspapers. One such was this article which gave a account of his military career up to that point.

“Lieutenant Wheeler-Nicholson comes from a long line of fighting stock, and has made a good record as a cavalry officer since his 21st year. He is an expert horseman and polo player and played last year with the Long Island polo team whilst a guest of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Carey Rumsey for the Wineloa Horse Show. He also was appointed judge of the Bryn Mawr Horse Show last Fall, whilst a guest of Vic Mathers, of the Brandywine hunt.”

“At the Plattsburg encampment, Lieutenant Wheeler-Nicholson won the high jump, and also much commendation for this work as instructor, and was presented with a watch in token of their appreciation of his work by members of the Knickerbocker Club, at a dinner given in his honor.” [“Local Boy is Popular,” OREGONIAN, July 30, 1916.]

SUNDAY OREGONIAN (July 16, 1916)

There were exceptions, though. On his way home for a several month-long 1917 leave of absence, an article ran in a Canadian paper covering the arrival of a mail steamer from China. Malcolm was noted as one of its passengers and received a few lines of print.

“Looking to participate in actual warfare, after the quiet of two years of garrison duty in the Philippines, Captain Wheeler Nicholson, of the U. S. Army, told The Times representative that he hoped to be assigned to duty on the Western Front. The captain wears decorations for expert marksmanship.” [“Japanese Shipping Increased by War,” VICTORIA DAILY TIMES, July 23, 1917.]

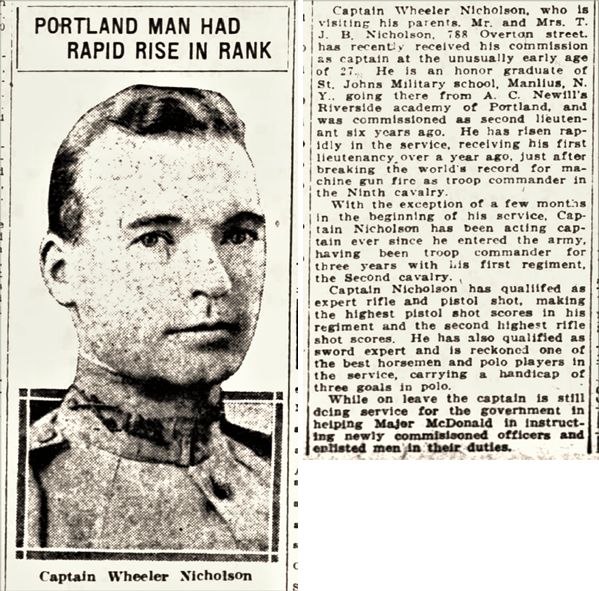

When finally back in Portland, the local newspapers were less restrained in their coverage of Malcolm’s homecoming. Several dinner parties in given in his honor were noted in the society columns and one article gave a summation of his military career up to that point.

“Captain Wheeler Nicholson, who is visiting his parents, Mr. and Mrs. T. J. B. Nicholson, 788 Overton Street, has recently received his commission as captain at the unusually early age of 27. He is an honor graduate of St. John’s Military school, Manlius, N. Y., going there from A. C. Newill’s [sic] Riverside academy of Portland, and was commissioned as second lieutenant six years ago. He has risen rapidly in the service, receiving his first lieutenancy over a year ago, just after breaking the world’s record for machine gun fire as troop commander in the Ninth cavalry.”

“With the exception of a few months in the beginning of his service, Captain Nicholson has been acting captain ever since he entered the army, having been troop commander for three years with his first regiment, the Second cavalry.”

“Captain Nicholson has qualified as expert rifle and pistol shot, making the highest pistol shot scores in his regiment and the second highest rifle shot scores. He has also qualified as sword expert and is reckoned one of the best horsemen and polo players in the service, carrying a handicap of three goals in polo.” [“Portland Man had Rapid Rise in Rank,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Aug. 20, 1917.]

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (Aug. 20, 1917)

While this glowing account of Malcolm’s service record can be partially explained as a reporter’s enthusiastic profile for a hometown boy, it also reveals some trends that would reoccur whenever his military career was discussed.

His ascendancy in rank was described as “rapid,” his commission as captain (which he actually achieved three days after this article was published) supposedly came “at the unusually early age of 27,” and that, except for “a few months at the beginning of his service,” Wheeler-Nicholson “had been acting captain ever since he entered the army.” All of these statements require parsing.

First, Malcolm’s rise in rank was basically in keeping with standard Time in Grade and Time in Service guidelines used by the U. S. Army. Before a Second Lieutenant can become a First Lieutenant, they must have first served 18 months at that lower rank. Malcolm entered the Army October 7, 1911 and became a First Lieutenant on July 1, 1916, meaning that he had almost five years in service at the time of his first promotion.

Wheeler-Nicholson’s next promotion to Captain came on May 15, 1917, less than a year after his promotion to First Lieutenant, when normal guidelines call for a two-year Time in Grade. However, as rapid as that was, it is explained by the fact that the United States entered the war in Europe (WWI) on April 6, 1917. Per Army guidelines, promotions can be made based upon need. As noted previously, the U. S. Army was facing a drastic shortage of officers heading into war. That is exactly why they instituted the Plattsburg “Businessmen’s Camp” in order to fill that glaring need. It also explains why Malcolm and other already in-service officers rose more quickly in rank. He wasn’t a special case.

So, too, it explains his age when promoted to Captain. As noted in the article, he was 27 years-old at the time; young, but well within the normal age range for a Captain, which starts at 25 years-old. And again, being wartime, age was far less an obstacle to promotion. One famous example was George Armstrong Custer, who became a Brigadier General at the age of 23 during the Civil War.

As for his being an “acting captain” since early in his service, that is also suspect. He received the same normal assignments for both a Second and First Lieutenant.

[All rank guideline information was obtained from the online U. S. Army portal, Army Officer Ranks and Promotions page: http://www.army-portal.com/pay-promotions/officer-promotions.html]

Malcolm also had the privilege of having his mother come stay in the Philippines during his tour of duty in that country. Antoinette’s position as a journalist, and with the probable aid of her political connections, allowed her to live near her son in the city of Manila for nine months. Apparently, her husband Thomas remained in Portland while she visited with Malcolm and then followed him to his next assignment in Siberia.

Near the end of the Great War (aka World War I), the United States became concerned about the ongoing turmoil in Russia, which was in the midst of their own civil war between the Czarist White Russians and the Communist Bolsheviks. Ostensibly, the Americans were being sent to protect U. S. interests in the region and lend support to the allied Czechoslovak Legion which was trying to fight its way out of Russia in order to join the other Allies on the Western Front.

Major General William S. Graves was placed in command of some 8,000 U. S. troops made up mostly of soldiers from the 27th and 31st Infantry Regiments. Both regiments were stationed in the Philippines and not otherwise engaged in any combat related to the Great War. Each was greatly undermanned and needed to be supplemented with additional troops. Wheeler-Nicholson was reassigned to the 27th Infantry and was aboard one of the first troop transport ships to arrive in Vladivostok, Siberia on August 15, 1918.

As Major Gen. Graves wasn’t to arrive in the country until September 2, there was confusion at the outset over the exact nature of the American mission. Unsure even of who was in charge, the American officers on the ground decided to follow the orders of the Japanese commander, Gen. Kikuzo Otani, whose forces were also in Siberia, but for their own reasons. There was long-standing animosity between Russia and Japan and the Japanese hoped that they could detach Siberia from the unstable country and use it as a buffer between it and Russia.

The initial actions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were to set up a camp at Vladivostok and unload their ships in the harbor. Malcolm later gave a reporter some detail of those first days.

“The Americans found fine brick barracks well equipped to house their troops in the extreme cold of the winter months and, incidentally, their first painful duty was to oust the hundreds of Russian refugees, mostly women and children in great need, who had installed themselves in these barracks and who had to be turned over to the Red Cross.” [“Russia is Land of Promise, Word of Major Nicholson,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Nov. 28, 1918.]

In the first weeks, the 27th Infantry marched from Vladivostok to Ussuri to the city of Khabarovsk, repairing and guarding railroad tracks along the way. They finally arrived in Khabarovsk on September16 and prepared for their winter encampment. They had experienced a few minor skirmishes with the Bolsheviks, but nothing at all resembling a battle.

“Between August 24 and September 15, the Twenty-Seventh Infantry suffered no combat casualties. The campaign was physically tiring, but not combat in the same sense as that on the Western Front or even the Allied intervention in northern Russia.” [House, Col. John M. (Retired), WOLFHOUNDS AND POLAR BEARS, 2016, pg. 78.]

While a couple of AEF companies supported Japanese forces in pursuit of some Bolsheviks after the Khabarovsk encampment, the majority stayed behind. Wheeler-Nicholson, who became a Major on June 7, 1918, would later claim that he was in command of the 27th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion, an assignment generally held by a lieutenant colonel or above. It is possible, given the shortage of officers, that he was assigned that command.

According to the date on his passport, Malcolm departed Vladivostok on October 27, 1918, just over two months after arriving. He made a short trip to Japan and China before returning to the United States for another leave of absence. His mother, who had stayed in Vladivostok during Malcolm’s entire Siberian deployment, made the same trip home. Antoinette arrived in Portland and gave a long report to the newspaper of the travels and adventures of her and her son, coincidentally the very day that armistice was declared ending the Great War.

MORNING OREGONIAN (Nov. 11, 1918)

“During her stay in Siberia, Mrs. Nicholson made her headquarters in Vladivostok, which city she describes as ‘the gayest of the gay, quite as colorful socially as is our own Washington, D. C., with every hotel turning guests away, and the restaurants ablaze with laughing, amusement-seeking throngs, who eat from morning to night, to excellent music. No matter at what time you go for a meal, you’ll find the same crowds eating joyously.”

“The naval and military atmosphere adds constant interest. But scratch beneath the surface and you’ll find the mad unrest of Bolshevism. It’s in the air in Vladivostok.”

“The Bolsheviki, wild-eyed men and women, bewhiskered just as their cartoons show them, dirty, unkempt and smelling to high heaven with accumulated filth, would hold secret meetings.” [“Secret Bolshevik Meetings Funniest Things in the World,” MORNING OREGONIAN, Nov. 11, 1918.

Antoinette’s account was a strange mix of political opinions, society page fluff and on-the-scene reporting. After describing some of her meetings with the “Bolsheviki” and others, she detailed some of the atrocities she said were committed by them and then circled back to recount her pleasant encounters with various Americans she met on her trip. There is also a quick mention that “Mrs. Nicholson is a descendant of a military family,” an odd claim that surfaces in almost every news story about her. It should be recalled that her father was a private for most of his military service and then served behind the lines as a surgeon for the rest.

Malcolm was not far behind his mother, as few days after her article appeared, he received similar attention in his own.

“Interesting stories of the American expeditionary forces in Siberia rolled out of the well-censored sleeve of Major Wheeler Nicholson, son of Mrs. A. W. Nicholson of this city, on this return to Portland after being stationed in Siberia for some months.”

“Major Nicholson speaks in highest terms of praise of the Czecko-Slovaks [sic] the most important ally there and whose numbers are made up of a superior type of men. Their gratitude to the Americans for their backing during the last months of chaos knows no bounds. They have all the qualities of German efficiency without the attendant characteristics of merciless cruelty.” [“Russia is Land of Promise, Word of Major Nicholson,” op. cit.]

Wheeler-Nicholson went on to relate some of the Bolshevik atrocities he, too, witnessed. The article finished on a positive note, though.

“Major Nicholson predicts a wonderful field of commercial opening up in Siberia as soon as law and order have been restored. The advent of the allies has been an eye opener to the Russian peasants and the country with its untouched resources, its undeveloped opportunities for agricultural work, is in a fair way to be the coming land of promise.” [“Russia is Land of Promise, Word of Major Nicholson,” op. cit.]

His leave over, in December Malcolm was reassigned to the Seventh Cavalry which was currently stationed at his previous post, Fort Bliss, in El Paso, Texas. His move was mentioned in yet another article about his mother that, along with details of her recent travels in the Philippines and Russia, contained some dubious claims.

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL (Jan. 18, 1919)

“Mrs. Nicholson has two sons in the army—Major Wheeler Nicholson, recently returned from Siberia and now in command of Custer’s old regiment, the Seventh cavalry, and Sergeant C. W. Nicholson, who is still in France.”

“‘My boys come by their military instinct quite naturally,’ said Mrs. Nicholson, ‘My father, Major C. Wheeler, was an officer in the Union army. He was a Virginian. My mother was born in Maryland. When my father espoused the cause of the Union all of his own family as well as my mother’s family disowned him.” [Lockley, Fred, “Journal Man at Home,” OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, Jan. 18, 1919.]

Virtually everything in these sentences is untrue.

Antoinette made the odd claim that surfaces in almost every story about her, which is that she is descended from a military family. It should be recalled that her father was a private for most of his military service and then served behind the lines as a surgeon for the rest. His rank as Major carried with it no battlefield responsibilities and was given as a matter of course to all surgeons in the army. He served in the military, to be sure, but it was hardly the sort of career that is usually recounted as the beginning of an illustrious military tradition.

She also states that her father was born in Virginia. He was not. He was born in Massachusetts, spent a few years in Illinois and never lived in the south until he moved there after serving in Tennessee during the Civil War. Antoinette made a similar false assertion about her mother. She wasn’t born in Maryland, instead she was Ohio born and lived in Illinois before moving to Tennessee with her husband. If any members of either of their families were against the Union cause, it certainly didn’t come because they came from a southern state.

On a related note: On her passport application of Aug. 12, 1918, Antoinette once again claimed that her father was a Virginian, even specifying that he was born in “Rockbridge County, Virginia.” Besides being untrue, making such a false statement on a passport was also a crime.

And perhaps her most glaring falsehood is the one stating that Malcolm was “now in command of Custer’s old regiment, the Seventh cavalry.” As a Major, he certainly was not in command of that entire regiment. He did, however, make quite an impression in other ways while stationed at Fort Bliss.

He was elected as the secretary of the Border Polo Association which matched polo teams from different regiments against one another.

EL PASO TIMES (March 9, 1919)

“Major Wheeler Nicholson of the Seventh cavalry stated yesterday that the outlook for classy polo in the series is bright, that every player in every four is a picked man for this particular post…” [“Polo Tournament is Arranged for at Fort Bliss; Will Run 10 Days First Game on this Afternoon,” EL PASO TIMES, March 9, 1919.]

And his name appears repeatedly in social events held at the base and the local country club.

“This dance is to be given on Friday evening and Maj. Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson, chairman of the committee of arrangements, states that various delightful and mysterious features for the dance will not be divulged until the evening upon which it is given.” [“Seventh Cavalry Officers Will Give Bolsheviki Dance Friday Evening at Country Club; Many Guests Invited,” EL PASO MORNING TIMES, April 29, 1919.]

EL PASO TIMES (April 29, 1919)

His busy schedule of polo playing and party planning came to an end in May 1919, when he was reassigned once more, this time to Camp Dix at Hoboken, New Jersey. His departure was noted sadly in the local paper.

“The game will probably be the last to be participated in here by Maj. Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, of the Seventh cavalry, who has been ordered to Hoboken, preparatory to going to France for duty. Maj. Nicholson, as manager of the Border Polo association for this district, has been untiring in his efforts to establish the popularity of polo with horsemen of the district and the fact that he has succeeded is apparent in the number of teams entered in the association and also in the number of lovers of the game who witness the weekly contests.” [“Credit Due Major,” EL PASO HERALD, May 24, 1919.]

Wheeler-Nicholson headed to his new assignment in June 1919, at precisely the same time four of the remaining American combat divisions were headed home. Malcolm was now with the 3rd Infantry, the last remaining division still in Europe, headquartered in Coblenz, Germany. The drawdown of troops was nearly complete, as the world attempted to restore normalcy after the Great War.

The transition of the wartime American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to the occupying American Forces in Germany (AFG) brought with it changes. One unwelcome change for any career army officer keen on advancement was the peacetime freeze on promotions.

“No more promotions of officers in the A.E.F. No more awards of decorations or certificates for meritorious service.”

“The lid on promotions and honors was put on when special telegraphic instructions from G.H.Q., under date of May 29 [1919], went out through the A.E.F., ordering that no more recommendations for promotions of officers to be forwarded, and that, save in very exceptional cases, no papers relative to decorations or certificates for special meritorious service should be sent in.” [“No Promotions, No Decorations,” STARS AND STRIPES, June 23, 1919.]

No longer were promotions going to be as easily attained as they were during wartime and, in fact like many, Malcolm’s rank was temporarily reduced to Captain once again.

More changes were to come. In early July, the 3rd Army officially ceased to exist and all forces at Coblenz now came under A.F.G. designation, with Major General Henry T. Allen in command. Then, in August, Brig, Gen. Frederick W. Sladen was tapped to head up the newly created First Brigade made up of several infantry battalions and the mounted cavalry detachment, all serving garrison duty out of Coblenz.

Malcolm, despite the claim in the July 6 OREGON DAILY JOURNAL that he had “transferred to General Pershing’s staff,” was actually granted a leave to attend classes at the Sorbonne in Paris. While there, he had the occasion to attend a garden party given in honor of a “Gen. Townsend,” likely a reference to British Gen. Sir Charles Townshend, a freshly returned prisoner of war and a highly controversial figure in his home country.

At this party, Wheeler-Nicholson met a young Swedish art student named Elsa Karolina Björkbom, who was also in studies at the Sorbonne. The pair began dating and their whirlwind romance resulted in a Dec. 1, 1919, announcement that they were to soon marry.

In the meantime, Malcolm finished his studies and was assigned to the Mounted Detachment stationed at Coblenz. This cavalry squadron was originally formed with an expressed purpose, unique among the American forces.

“The Squadron was formed for show purposed but it was also understood that it was to be representative of the best American cavalry. With such a goal in view it was little wonder that the Squadron soon made itself prominent in a military way and in other directions.”

“Under the very able leadership of Lieut. Col. J. M. Wainwright the Squadron grew to be one of the foremost organizations in the A.F.G. It has many times been honored in being the personal escort of t he leading civil and Military [sic] personages of the allied Nations…”

“Lieut. Col. Wainwright has been succeeded in the order named by Major S. F. [sic] Winfree, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson and Captain R. L. Coe. Captain Coe has been in command since January 1921.” [“Mounted Detachment, Ehrenbreitstein,” REVIEW OF THE AMERICAN FORCES IN GERMANY, pg. 138, Sept. 1921.]

Wheeler-Nicholson was following in some impressive footsteps. Lieut. Col. Wainwright would gain fame during WWII, when in May 1942, as commanding General of the American troops in the Philippines after Gen Douglas MacArthur was evacuated, he was forced to surrender Corregidor Island to the Japanese. Wainwright suffered terribly as a prisoner of war along with his men and when released at the war’s end, he received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Immediately preceding Malcolm in command was his long-time friend and the eventual Best Man at his wedding, Major Stephen W. Winfree, who had served with Wheeler-Nicholson both in the Philippines and Siberia. The wedding itself was a fairy tale-like event that received a huge write-up in a Portland newspaper.

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, pg. 1 (June 4, 1920)

“Amid the pomp and pageantry common to royalty alone, Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson, Seventh cavalry, U.S.A., son of Mrs. T. J. B. Nicholson, 505 College street, Portland, was wed May 1 [1920] to Baroness Elsa Karolyn Bjorkburn [sic].”

“Accounts of the international incident have just reached Mrs. Nicholson.”

“Preceding the wedding, a representative of Nicholas, king of Montenegro, decorated the bridegroom with the cross of the Order of Danillo, in recognition of service performed for the Montenegrin people.” [“Major Nicholson Weds Daughter of Noble Line,” OREGON JOURNAL, June 4, 1920.]

Allowing for the minor typos and misspellings, this article also exhibited some of the exaggerations that commonly appeared in newspaper accounts about Malcolm which by way of his mother, Antoinette.

While his bride Elsa reportedly came from a family of royal blood, she was not a “Baroness.” And the “Order of Danillo” awarded to Malcolm “in recognition of service performed for the Montenegrin people,” had a somewhat less-than-noble reason behind it.

“Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson,” began Jerome Coignard’s column, “once introduced Douglas Fairbanks to an old gentleman who was having a drink with the author [Malcolm] at the bar of the Hotel Meurice [in Paris]. Wheeler-Nicholson then took the delighted grandpa to the movies to see Fairbanks in a film. And the next morning he was routed out of bed by two officers in a strange uniform, who pinned a medal upon him as the thanks of King Nicholas of Montenegro for an evening’s entertainment.” [Coignard, Jerome, “Very Small Talk,” Nov. 20, 1929.]

King Nicholas was the deposed king of that small nation which had been absorbed into the newly created Yugoslavia at the end of the Great War. He was living in Paris in exile when he met Malcolm and would die soon after, on March 1, 1921.

“Fourteen brother cavalrymen who had served in various regiments with the bridegroom during the last 10 years made possible an old-fashioned cavalry wedding with the guard of honor for the bride, an arch of swords, fluttering guidons and glittering side arms.”

“General [Henry T.] Allen, commander of the United States forces in Germany, led the bride to the altar, preceded by Miss Florence Preston of Paris, maid of honor. Colonel Stephen Winfree, assistant military attache at Constantinople,was best man.” [Ibid.]

Elsa’s father, Karl Teod Valfrid Björkbom, died in 1916, explaining why Gen. Allen had the honor of escorting her down the aisle.

“A reception at the Coblenzer Hof was followed by a dinner and dance at the allied officers’ mess in honor of the bridal couple. The bride cut the cake with the bridegroom’s sword, according to ancient custom.”

“Two chests of massive silver, mainly heirlooms, were among the presents from various branches of the families and a notable gift was that sent by the cavalry officers, a massive beaten silver bowl inscribed with names and date.”

OREGON DAILY JOURNAL, pg. 3 (June 4, 1920)

While the bulk of the article was filled with such details, it also went into a brief summary of their meeting and engagement, along with a little editorial comment, likely via Antoinette.

“The engagement was announced last autumn and the wedding was to have taken place in Stockholm, the home of the bride, in December, but an indifferent government kept the bridegroom jumping about Europe so rapidly he had no time to establish the residence required by law in Sweden before marriage and the wedding had to be in Coblenz.” [Ibid.]

Those few lines of commentary about the “indifference” of the army would portend an attitude which came to the fore a few months hence.

The article finishes with a detailed recitation of Wheeler-Nicholson’s military career, the revelation that the couple was collaborating on a book of military history and a paragraph assuring readers of Malcolm’s ongoing popularity in Portland and how both he and Elsa enjoyed their friends “in both civil and military circles in France and England.” [Ibid.]

Their honeymoon would take them from Germany, to France, to England. Unfortunately, though, the honeymoon didn’t last forever. The circumstances leading to it weren’t specified, but a few months after getting married, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson was relieved of his command.